When Loftus Peak first began taking investor funds four years ago, there was a perception that smartphones and Google searches meant the world was hooked up and the big disruption money had already been made in the sharemarket, so further pickings would be slim.

But that is not the way it went. Facebook closed above US$38 a share on its first day of listing in 2013, halved thereafter, and then went up 10 times to more than US$200 on the back of the company’s successful shift to mobile (after a panic that the company could not make the leap from the desktop).

Markets struggle with long horizons

Markets react to visibility and can struggle to ascribe value beyond a two-year horizon. The sheer size of some of the disruptive themes might help understand the dilemma markets face in correctly valuing the affected companies; that is, all companies.

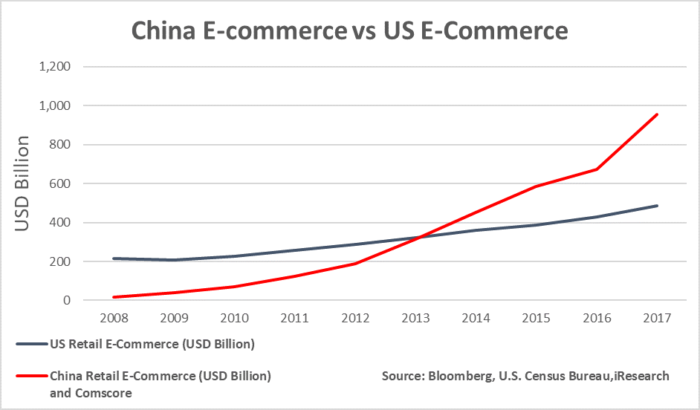

There are secular trends that will not reach their addressable market size in a single quarter but will keep expanding faster than GDP for years to come. For example, one of the strangest valuation anomalies was Alibaba, which investors thought was fully valued based on its hold on the Chinese e-commerce market. That market is already bigger than the US, is growing faster and has several years before it hits maturity, as the chart below shows. The stock has doubled since listing.

These big trends - such as energy as a technology (not a fuel), networks, connected devices (sometimes called the internet of things) and mega-data - will play out over decades. Single-period valuation methodologies such as price-to-earnings are too inexact, but it is a statistical certainty that 10-year forecasts will be wrong, too.

What has become clear is that such longer-term thinking when combined with other key metrics provides 'less wrong' valuation parameters compared with concentrating the investment horizon to one or two years, which can lead to a game of valuation catch-up. For example, there are serious problems in the world of central processor unit (CPU) chips. You shouldn’t be reading this here first, but Gordon Moore’s law that the number of transistors on a chip doubles every 18 months, is now breaking down.

It isn’t the CPU that will make computers go faster, it is graphics processor units and the like. They will not just double the speed, their advent into the data centre will mean an over 10-fold hike. Moore’s law drove disruption, but it is not fit for purpose from here. It will be different architectures that make processing speeds faster, thus increasing the pace of change.

Intel itself has acknowledged this, stating in 2015 that the pace of advancement has slowed. Brian Krzanich, the former CEO of Intel, announced: “Our cadence today is closer to two and a half years than two.”

Greg Yeric, chip designer at rival ARM, says:

“As Moore’s law slows down, we are being forced to make tough choices between the three key metrics of power, performance and cost. Not all end-users will be best served by one particular answer.”

This thematic will not play out in one year. It has already taken half a decade and is only halfway through.

Investing in global megatrends

There is an interesting line between being a disruption investor relative to that of a technology investor, meaning that it is more important to understand Moore’s law, not because it leads to smaller chips but because of what new business models arise as a consequence.

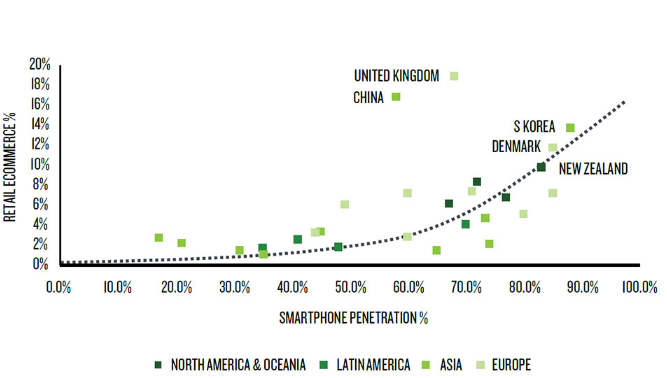

The chart below shows the growth of smartphones, a direct result of Moore’s law, but also their relationship to retail ecommerce (as a proportion of all retail), a disruptive business that was not necessarily foreseeable.

The relationship between retail e-commerce and smartphone penetration

Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company

It's not only about increasing processing speeds

It is the same with 5G. The technology itself may not be investable, but the changed business models that arise from it may be. For example, all the fancy processor power rolled out in the past 50 years could not even cope with a YouTube cat video until broadband speeds – meaning money in fibre and cell towers – caught up on a national and international scale. If self-driving cars become ubiquitous, it will be because there is 5G processing power, with the attendant massive real time data-transfer rates, to help steer them safely.

Meanwhile, Amazon has built a web services company that is at least as valuable as its US retail business and is now close to having an unassailable lead in voice, with the stock up five times in four years.

Voice is the next battleground in search, and both Google and Apple are behind Amazon in its execution here. We think about how this will impact business models on a multi-year horizon. And it isn’t because of the machine learning tools that drive voice, but the business implications of having an Alexa device in your home organising your shopping.

And so it is with Netflix. The company is not just an entertainment service, its model threatens to upend networks and pay-TV as we know them, globally. The fact that there are no real barriers to entry other than capital, for Hollywood film studios to create competitors to Netflix, has not stopped them from completely missing the point about the company and its role as a cable-TV killer.

Disney and Comcast were beating each other over the head to double down on old media by trying to buy 21st Century Fox for more than US$60 billion – a bid in which Disney won, at a cost of US$71.3 billion – presumably on the principle that scale will solve bad per unit economics, but it won’t.

What they should be spending that money on is great content, which is what’s really keeping Netflix’s share price moving. AT&T sort of gets it with the acquisition of Time Warner but is going to wind up so leveraged it will not have the additional resources to bring the fight to Netflix, content-wise.

There are other developments across sectors as diverse as energy, finance, robotics and transport. Four years after we started in this company, we believe there is still return to be had from the sharemarket, provided we continue to focus on the important trends and keep an eye on valuation. This remains our daily focus.

Alex Pollak is Chief Executive, CIO and Founder of, and Anshu Sharma is Portfolio Manager at, Loftus Peak. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.