This article examines credit spreads, how they relate to share prices and what they can reveal about where we are in the stock market cycle.

What is a credit spread?

The ‘credit spread’ on a company bond is the extra yield demanded by investors over and above the yield on a government bond for the same term, to compensate the investor for the higher risk of loss if the borrower were to default on payment of interest or principal.

The ‘riskier’ the bond, the greater the extra yield (spread) demanded by investors. For example, a 5-year government treasury bond may trade on a yield of 2.0% per year (in early May 2016), but a 5 year ‘investment grade’ company bond might trade at 3.5%, a 1.5% credit spread above the yield on government treasuries. A sub-investment grade ‘high-yield’ (‘junk’) bond might trade at 7%, a 5% credit spread above treasury yields, because of its greater risk of default.

The extra yield return on a high-yielding bond might look attractive to investors at first sight, but if the company defaults during the term of the bond, the investor might only recover say 70% of their capital in a liquidation, creating a 30% capital loss, so the higher perceived return via higher yield may be illusory. Although bond markets are far from efficient and rationally priced, there is a good chance that the higher income yield on a risky bond will be offset by a capital loss on the principal and/or loss of interest, leaving the investor no better off than they would have been with a treasury bond.

How credit spreads change over time

Credit spreads do not remain static over time. They rise (widen) and fall (tighten) with the changing level of pessimism or optimism about the health of the corporate sector. This same pessimism or optimism is also a major driver of company share prices.

Shares tend to do well when spreads are declining (tightening), and shares tend to do poorly when spreads are increasing (widening). One does not cause the other – they are both measures of investor sentiment about the health of the corporate sector. This phenomenon has been evident over the past century of market data but here we focus on the past couple of credit cycles to highlight where we are at the moment.

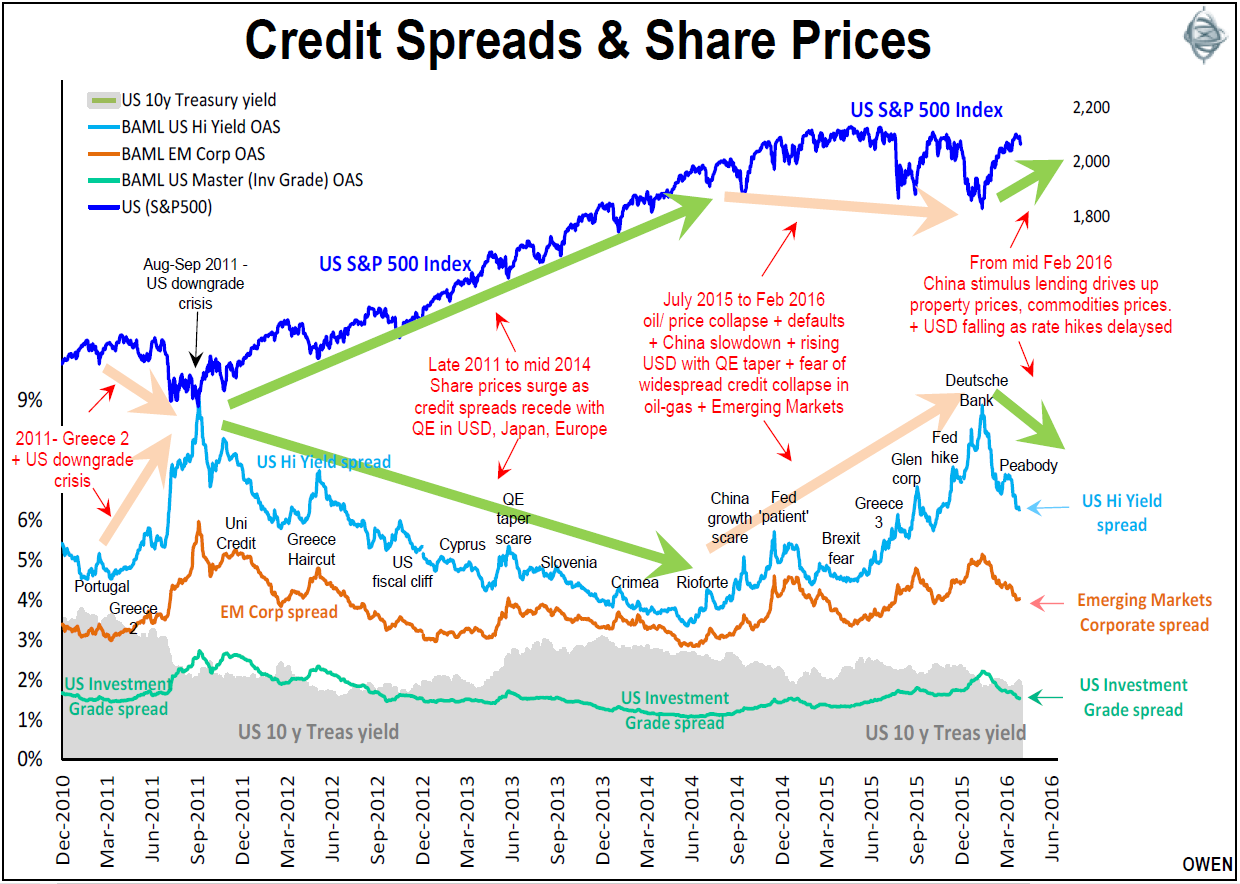

The first chart shows the US S&P500 share price index from 2011 (top of chart) and three different credit spread measures (bottom section).

Credit spreads tend to move in parallel paths, but credit spreads and share prices have tended to move in opposite directions, as illustrated by the pairs of green and orange arrows on the chart. The chart highlights the key events that have driven market sentiment, credit spreads and share prices through the past couple of credit spread cycles.

What about Australia?

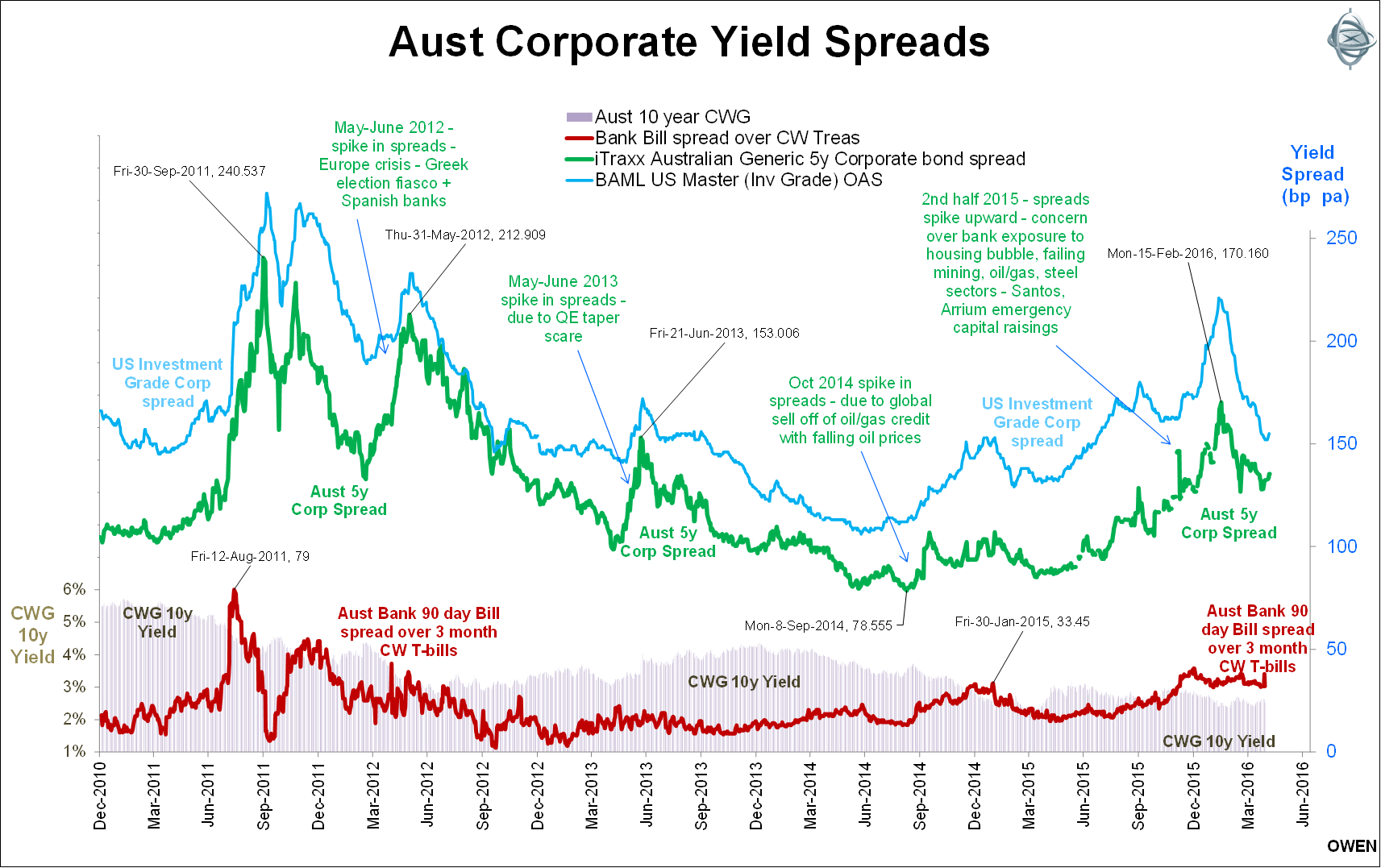

Since the Australian bond and stock markets are mostly owned and driven by foreign money, our local markets tend to follow global trends. The next chart shows average 5-year Australian corporate bond spreads (green line) following the same ups and downs as US investment grade spreads (light blue) over the same period as the first chart.

The peaks and troughs in US credit spreads are echoed consistently in Australian spreads.

The above chart also shows Australian bank spreads (maroon line), which is the spread between the 90-day Australian bank bill yield and Commonwealth 13-week Treasury bill yields. This bank spread represents the perceived degree of short term credit risk of banks. Yes, Australian banks are risky! (This bank spread pattern is also useful in helping determine when securities priced off bank bill yields – e.g. floating rate securities like bank hybrids – are expensive or cheap).

What lessons can we learn?

Both the charts show that spreads widened rapidly in early-mid 2011 as the banking crisis escalated in the European PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain) and in particular during the Portuguese bailout and as Greece headed toward its second bailout. Spreads widened further and peaked in August-September 2011 with the US credit downgrade crisis when rating agency Standard & Poor’s took the radical step of stripping US government debt of its AAA rating. There was a fear the US government would default on its debts. The US government did indeed have to close down the government for a month in 2012 because it could not pay its bills. Credit spreads were at their highest since the 2008 sub-prime crisis.

The most recent peak in credit spreads and trough in share prices was in February 2016. Several factors were causing the general market pessimism, such as:

- worries over the pace of US rate hikes and their possible impact on company profits and share prices

- a possible hard landing in China, exacerbated by the crash in Chinese share prices

- the escalation of oil/gas/steel bankruptcies

- cracks in the European banking system led by fears of possible default by Deutsche Bank.

February 2016 compared with 2011

To me the level of fear and pessimism (measured by spreads) in 2016 was significantly over-done as conditions were not nearly as severe as they were in 2011. In mid-2011 we under-weighted shares in portfolios before they sold off heavily during the US downgrade crisis. This time, we did not take evasive action because it appeared that spreads (fear) had over-shot reality, and shares had been sold down too far.

Three key factors are likely to see spreads fall from their February 2016 levels and share prices stabilise and even recover:

- the renewed resolve of the Chinese government to fund investment and credit to support growth (this was subsequently formalised at the National Congress in March)

- the continued dominance of Fed Chair Janet Yellen over the ‘inflation hawk’ dissenters, and the resultant ‘go-slow’ on US interest rate hikes

- the ECB’s continued commitment to negative rates and broadening QE in Europe.

These factors led to a degree of confidence that the sell-off in stock markets would probably not continue much longer or further, unlike in 2011 and 2008. Since mid-February, share prices have recovered a little while credit spreads have eased (tightened).

Credit spreads represent only one factor, but they can be a barometer that helps determine where we are in the share market cycle.

Ashley Owen (CFA, BA, LLB, LLM, Grad. Dip. App. Fin) has been an active investor since the mid-1980s, a senior executive of major global banking and finance groups, and currently advises HNW investors and advisory groups in Australia and Asia. This article is general information only and does not consider the personal circumstances of any individual. Readers should obtain their own advice before taking action.