Traditional value investing has run its course and it will be ineffective in a low growth, disrupted world. However, good qualitative analysis and the determination of long-term intrinsic value will always remain relevant.

Value investing can be a rational investment strategy, and the so-called 'value effect', or anomaly, has been identified in numerous academic studies. These studies found that buying portfolios of stocks with below average price to book (P/B) ratios or price to earnings (P/E) ratios resulted in alpha generation that could not be explained by the efficient market hypothesis. This hypothesis states share prices reflect all relevant information and it is impossible to beat the market or achieve above-average returns on a sustainable basis.

But times have changed

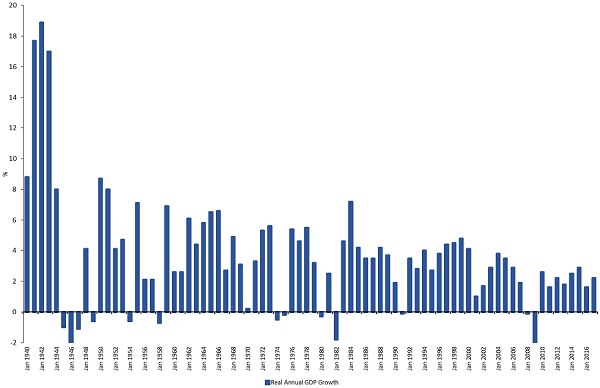

However, our base case is that traditional value investing will be far less successful in future than it has been in the past. From World War II until the GFC in 2008, we saw a period of strong economic growth in the US and most other major economies, largely attributed to a perfect storm of positive factors:

- low oil prices (except for two relatively short periods from 1974-1983 and 2006-2008)

- the commercialisation of a broad range of technological advances

- a growing middle class (in developed economies up until the late 1970s)

- increasing female participation in the workforce

- young and growing populations.

Figure 1: US real GDP growth was strong from WWII until the GFC

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Hyperion

Traditional value investing relies heavily on finding companies which are themselves heavily reliant on a strong economy to create compounding earnings growth. These types of businesses are more often average rather than high-quality businesses. Quality businesses typically trade at short term premiums to the broader market.

Strong economic growth hides a multitude of business sins

From WWII to the GFC was also a period of benign competitive intensity. Technology-based disruption was low, and average businesses were able to sell average products to middle-income consumers with reasonable success. Many of these businesses lowered their costs by outsourcing manufacturing and other services to low-wage emerging markets. Corporate consolidation was supported by declining borrowing costs, where mediocre businesses had a reasonable probability of being taken over.

On the other hand, when the economy experiences low or negative growth, average businesses tend to suffer disproportionately. Profits of average businesses are leveraged into economic growth because they can usually grow sales organically in line with nominal GDP. With the help of operating and financial leverage, these companies can then grow profits above the rate of sales growth.

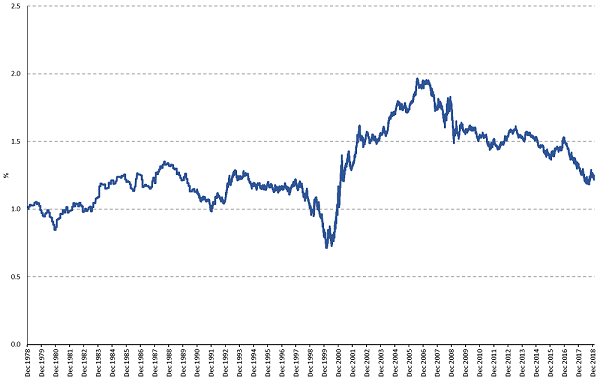

Figure 2 illustrates what has happened since the GFC. The value anomaly had largely disappeared and value has underperformed growth since 2007. Lower levels of economic growth have forced businesses to act more aggressively to boost sales, and the general level of technology-based disruption has increased substantially.

Finally, average businesses are usually capital intensive, without substantial pricing power, and therefore need to use debt to boost their return on equity. Many of these businesses were forced to undertake equity raisings during the GFC at low prices, which were highly dilutive to earnings per share (EPS) and portfolio returns.

Figure 2: Russell 1000 Value Index/Russell 1000 Growth Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, Hyperion

Growth managers have been outperforming value managers for the past decade

According to the 2019 Morningstar Australian Institutional Sector Survey, the average growth manager has outperformed its value counterparts in global equities by 197 bps p.a. (1.97%) and 64 bps p.a. (0.64%) over 5 and 10 years, respectively. The average growth manager has outperformed its value counterparts in Australian equities by 161 bps p.a. (1.61%) and 107 bps p.a. (1.07%) over 5 and 10 years, respectively.

Traditional value investing generally relies on predicting short-term P/E movements within historically observed ranges. These short-term movements determine whether a company is considered for investment when benchmarked against its comparable ‘peers’.

For historical P/E averages or ranges to be meaningful, the underlying earnings and intrinsic value of an average company needs to rise over time, and the P/E ratio needs to mean revert. But for P/E ratios to mean revert, corporate profits need to grow steadily. And for corporate profits to grow steadily, credit and consumption across the economy also needs to be growing as a result of ongoing scale and productivity benefits.

Value investing also relies on the assumption that profits will not decline permanently over time.

Investing in stocks which appear to be cheap because valuation metrics such as P/E ratios are low over an extended time period can, in fact, be what is called a ‘value trap’. The value trap springs when investors buy on the basis that profits will lift, and the opposite happens. Companies languish or drop further.

For example, if a stock is trading on a P/E multiple of 12x relative to its long-term average of 15x, a value investor would look to purchase the stock at a 20% discount to its long-term average (for a potential 25% gain), with the expectation that the multiple will ultimately revert to its historical average, and the earnings of the business will also grow in the future.

This P/E arbitrage approach is rational if:

- share prices are rising over time

- the economy is growing in real terms

- the business model, management team or industry structure have not changed structurally.

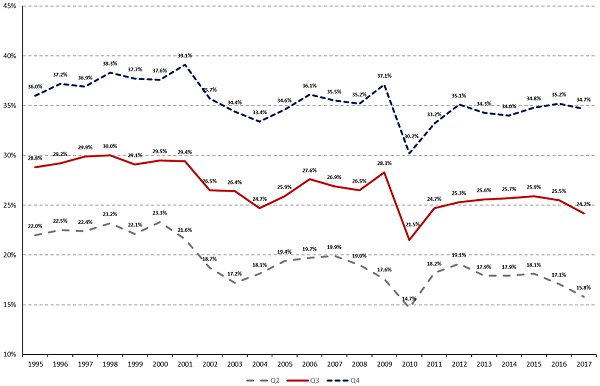

However, if earnings growth moderates or there is market disruption, mean reversion becomes harder and value traps emerge more frequently as share prices remain permanently depressed. Following the GFC, the return on equity of average and below-average companies has been declining because of increasing levels of disruption as shown in Figure 3 ('quintiles' divide data into five equal parts, so the middle three quintiles remove the best and worst companies from the data base).

Figure 3: Profitability persistence - three middle quintiles (MSCI World Index)

Sources: UBS; Hyperion Asset Management. Note: Operating profitability (OP) equals operating profits (sales minus cost of goods sold minus selling general and administrative expenses minus interest expense) divided by book equity at the last fiscal year end of the prior calendar year.

History does not always correctly inform the future

Historical P/E ranges are not relevant if the long-term earnings outlook of a company is deteriorating through time. This is because the P/E will remain depressed as the earnings outlook deteriorates, resulting in a significantly lower intrinsic value.

In our example above, the correct P/E could in fact be 9x, which would mean a 25% decline in share price rather than the anticipated 25% gain. In addition, if the earnings are declining then the capital loss will be enlarged because a depressed P/E will be applied to progressively lower EPS figures through time.

If the business has significant debt, then the equity value of a structurally-challenged business can quickly decline to zero if lenders get nervous and call in the administrators. Traditional, low P/E value stocks did not provide capital protection in the GFC. Earnings for many businesses proved to be illusionary while their high debt levels persisted. Many of these ‘cheap’ low P/E businesses never recovered.

In a structurally low-growth and disrupted economic environment, we believe simple short-term value heuristics such as low P/E or P/B ratios will not be effective.

For value investing to remain a rational strategy, mean reversion must hold true, and for this to happen, economic conditions need to be supportive or at least steady. And the reality is that historical ranges are no longer relevant to companies losing market share or with fundamentally challenged business models. This is when value traps emerge and share prices can remain permanently depressed.

We believe qualitative analysis is becoming far more important in a low growth world. Attractively-priced companies with the ability to compound earnings and free cash flows over long time periods are the only ones which will generate substantial outperformance.

Mark Arnold and Jason Orthman are the Chief and Deputy Chief Investment Officers respectively at high-conviction equities manager, Hyperion Asset Management. This article does not consider the individual circumstances of any investor.