There is an alarming rise in Chinese corporate debt and a steep rise in the early warning signs of creditor distress. China’s corporate debt has been the driver of China’s overall steep increase in debt to GDP. Global debt to GDP ratios have risen since the GFC, but in most other countries it is government sector that has been behind the rise, particularly in Europe and Japan. China is a special case as the governments often own the corporations, making the use of loans between state and corporations a greater risk to China’s overall economy.

This article looks at some of the specific drivers of corporate debt in China such as property, shadow banking and local government debt. But before we do that, here’s some further context on the world debt situation.

State-owned enterprise default

The most recent default, Dongbei Special, is a little-known steelmaker, but provides a great example of significant issues for the Chinese economy and therefore for Australian investors.

Dongbei Special is a state-owned enterprise that defaulted on USD131 million in debt underwritten by China Development Bank, another state-owned enterprise, on 28 March 2016. It owes a further USD150 million in short-term notes issued outside the banking sector, through shadow banking channels. A default of a local government-owned enterprise is rare, but likely to become an increasing problem particularly amongst parts of the economy, like steelmaking, that have been artificially propped up by government support and lending.

Global context

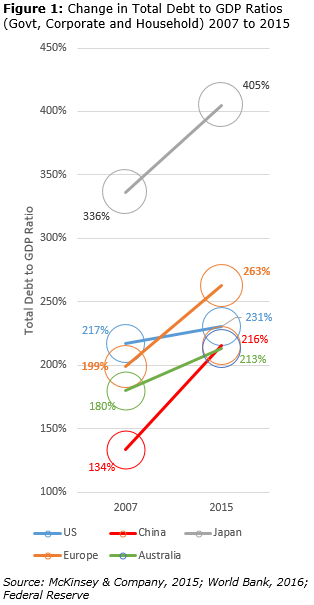

During the period 2007 to 2015, global debt (excluding banks) grew by around USD28 trillion. Nearly 33% of this was from China, and most of that was from the household and corporate sectors. A further 25% came from European governments and another 12% from the Japanese government.

The impact of these jumps in indebtedness was to rapidly increase the total debt ratios for these economies, but China’s growth in debt, albeit very steep, has only brought it in line with the US and Australia. Europe on the other hand has raced ahead of the US and China, and while still trailing Japan today, has already reached Japan’s total level of indebtedness in 2004.

Given the current pace of growth in these economies, Japan and Europe are the greatest concerns. The US has had relatively little increase in total debt despite the massive government fiscal and monetary stimulus programs run during that time, simply because households and the corporate sector deleveraged over the same period. Figure 1 shows the pace of growth in China’s indebtedness.

Chinese debt is not unusually high in terms of its Total Debt to GDP Ratio. It is more or less the same as Australia. But recent growth rates have been very high and rising, and we need to question the sustainability of that credit growth and therefore China’s overall economic growth.

If Chinese growth stalls, there will be an immediate, negative flow on to the AUD, our share market, and particularly, resource stocks.

Pace of growth in China’s corporate and household debt

There are three primary causes of the sudden growth in private sector debt in China over the past eight years:

1. Property development

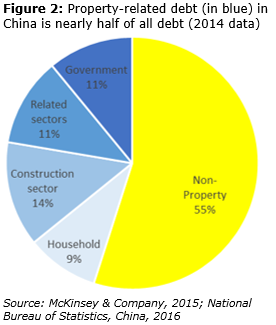

An estimated 45% of all Chinese debt is related to property. The mix is shown in Figure 2. Property construction alone represents 14% of all debt, and it is important to understand who the key lenders are to this sector.

China shows a very high level of overdevelopment, particularly in Tier 3 cities where the average time to sell developments is around 40% above historic levels.

The unusual figure in this chart is the 11% of total debt that is owed by local government entities for property or infrastructure projects, far higher than any other country.

2. Household exposure and shadow banking

Household debt has grown from USD1.0 trillion in 2007 to USD4.4 trillion in 2015. Mortgage debt makes up USD2.1 trillion of this, but small business related loans have jumped from $0.3 trillion to $1.4 trillion over the last eight years.

Again on a standalone basis this is not out of line with the rest of the world. Household debt in Australia, for example, is 113% of the GDP, in the US it is 77%, in Europe around 70%, and in Japan 65%, compared to just 38% in China.

What is more concerning is the household sector’s exposure to the property sector through ‘shadow banking’. Shadow banking simply refers to finance providers that typically take deposits from households and lend to businesses, including property developers, such as the debenture finance companies in Australia and New Zealand, such as Westpoint.

Shadow banking now accounts for USD6.5 trillion including around USD4.5 trillion from households, and is growing at twice the pace of the banking system and three times government debt growth rates. Again a slowdown in property would severely damage the economy, this time through consumer confidence and spending.

3. Local government debt

Local government debt has increased by 27% per annum since 2007 compared to 11% pa growth for central government debt. Local government debt now sits at USD2.9 trillion or around the same debt as the entire German government. More than 70% of this relates to property, as above. The key concern for these local government entities is the reliance on land sales to repay the debt, meaning that if the property cycle suddenly slows, many of these entities will be forced to refinance, placing considerable stress on the banking system, as much of this debt is via financing vehicles funded by the banks.

Strategy for investors

For Australian investors, this emerging debt situation must be watched carefully throughout 2016. It is becoming the largest threat to the Chinese economy. China’s health in turn is the largest threat to the Australian economy, its currency and its equity market. Investors looking to hedge their own wealth against a shock to the Chinese economy can either shift risky assets into safe harbour assets such as infrastructure bonds or equity; or they can place some of their Australian dollar positions into USD or GBP positions to profit from the falling AUD that would most likely follow any increase in risk relating to China’s indebtedness.

Craig Swanger is Senior Economist at FIIG Securities Limited, a leading fixed interest specialist. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.

Each year, FIIG Securities produces its Smart Income Report on the economic outlook and macro trends, and the 2016 version can be obtained on request, linked here.