Diversification. The word once appeared to suggest higher returns delivered with lower risk. Through the GFC however, diversification’s fabled benefits appeared to vanish just when needed most, leaving many disillusioned. So what does diversification actually promise, and what can it realistically deliver? In this trilogy of articles we’ll look at diversification through a retirement planning lens, from its earlier incarnations to its potential future applications.

Diversification through the ages – from Shakespeare to Sharpe

One of the earliest references to diversification appears in Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’. The merchant, Antonio, when asked whether his melancholy might be due to worrying about his ships at sea, says…

Believe me no. I thank my fortune for it –

My ventures are not in one bottom trusted,

Nor to one place, nor is my whole estate

Upon the fortune of this present year.

Therefore my merchandise makes me not sad.

Antonio, in owning more than just one vessel, was applying the principles of diversification. He knew that while it was possible that one of his ships might be lost on any one voyage (denting his wealth a little), it was extremely unlikely that all his ships would be lost (in different seas and weather conditions) at the same time, leaving him destitute. Thus from the earliest days, diversification was recognised as a tool better suited to avoiding financial disaster than to maximising wealth. Another 350 odd years passed before diversification’s investment benefits were quantified in a 1952 paper titled ‘Portfolio Selection’ written by a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago.

Enter the diversification engineers

In writing his doctoral dissertation on the role of risk in investing, Harry Markowitz applied the concept of variance, a statistical measure of ‘spread’ around an average outcome. He used variance as a measure of risk, with a risky investment being one with a large range of possible outcomes around its expected return. Markowitz was thus the first person to put a number on investment risk, albeit a risk metric that primarily measures the volatility of returns. Today a close relative, standard deviation, is the most commonly used measure of risk in institutional asset management.

Markowitz demonstrated in mathematical terms how investment diversification works: you can have two individually risky assets (high standard deviations) and yet combine them to produce a less risky portfolio (his choice of words) provided the two assets do not move in identical fashion in response to the same stimulus. This co-movement is known as correlation, and the lower the better. Thus a portfolio consisting of just two shareholdings, one an ice cream maker and the other an overcoat maker, should result in a less risky outcome than holding either in isolation. The seasonal variations in temperature would benefit one if not the other.

William Sharpe wrote part of his doctoral dissertation under Markowitz and took his supervisor’s ideas further in the early 1960s when he recognised that the single biggest influence on the direction of a company’s share price was the direction of the share market as a whole. He also noted that investors were, by then, able to diversify their shareholdings relatively easily and at low cost. Sharpe surmised that the benefits of diversification were available to all, and as such investors should not expect to be compensated for risk that could be diversified away by holding a broadly-based share portfolio.

Sharpe introduced the dichotomy of diversifiable (company-specific) idiosyncratic risk and non-diversifiable systematic (market) risk. He felt that investors in competitive share markets should only expect above-market returns from any systematic risk they choose to hold in excess of market risk. In short, in the absence of superior and enduring investment insight, to beat the market you have to accept more risk than the market.

Together Markowitz and Sharpe provided a theoretical foundation for diversification. These efforts saw both awarded (along with Merton Miller) the 1990 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences “for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics”. At heart however Markowitz and Sharpe were merely expressing mathematically the practical wisdom in two age-old sayings: “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” and “Nothing ventured, nothing gained”. The aim of all prudent investing is to find the right balance between these two adages.

Asset classes – Diversification grows up

Markowitz and Sharpe were concerned primarily with risk and return from a share market perspective. Investors tend to hold their wealth in assets other than just shares. Prudent investors will allocate wealth across a number of asset classes, each with its own risk/return characteristics. At the highest level these asset classes are cash, fixed interest (debt), shares (equity) and property.

The diversification principles underlying portfolio construction have changed little in the past 50-odd years. The process starts with an investment policy which states the overarching investment objective(s) and the acceptable risk/return trade-offs. Asset classes are named as are their policy weights. Taken together these form the portfolio’s ‘Strategic Asset Allocation’ (SAA). Each asset class will have a benchmark against which performance is monitored. Finally an allowable limit might be set for intentionally deviating from the SAA to take advantage of perceived shorter-term valuation anomalies (often termed tactical or dynamic asset allocation).

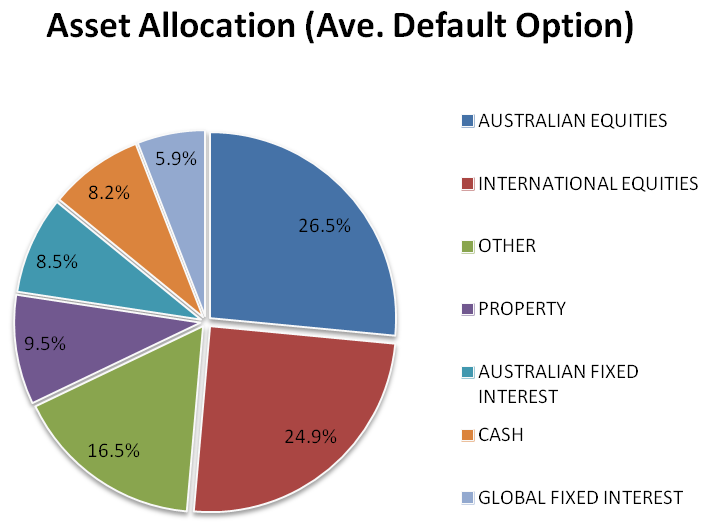

How does all the above translate into the real world? As the SAA ‘pie chart’ that has become a ubiquitous part of investing today. Below is the current asset allocation of the average default superannuation fund option, offered by Australian super funds, as compiled by global consulting firm Mercer:

Source: Financial Services Council, Asset Allocation of Pension Funds Around the World (February 2014)

As the chart indicates, some 51.4% is allocated to equities, both domestic and international. Together with property, the total allocation to ‘growth’ assets sum to almost 61%. Part of the 16.5% in ‘Other’ might also have growth-like characteristics, such as allocations to private equity, hedge funds and certain types of infrastructure.

By investing across various asset classes, superannuation funds seek to apply Markowitz and Sharpe’s principals of diversification. Pie charts tell us how capital is allocated. They tell us little, however, about how risk is allocated. In the next article we turn our attention to the risks embedded in diversified portfolios such as the one above.

Harry Chemay is a Certified Investment Management Analyst who consults across both retail and institutional superannuation, focusing on post-retirement outcomes. He has previously practised as a specialist SMSF advisor, and as an investment consultant to APRA-regulated superannuation funds.