Investment professionals need to communicate as clearly as possible, and some classifications which market experts think are obvious can be confusing. This is a short piece with a few simple ideas on some investment descriptions. Anyone expecting a great piece of gravitas from me here will be disappointed.

In my view, many institutional investors follow herd-type thinking, without robust logic, because everyone before them followed the same line of thought. My many years of experience in investment markets have caused me to dismiss some of this traditional thinking. Much of what is preached is not robust enough in my view and I am not alone in my skepticism, though certainly in a minority. The investment community is prone to putting concepts into neat little boxes, which does not work because investing is more of an art than a science, despite the continued attempts to make it a more predictable subject.

Thinking about risk and return

A good example of what I am talking about is the distinction between defensive assets and growth assets and their relationship to risk and return.

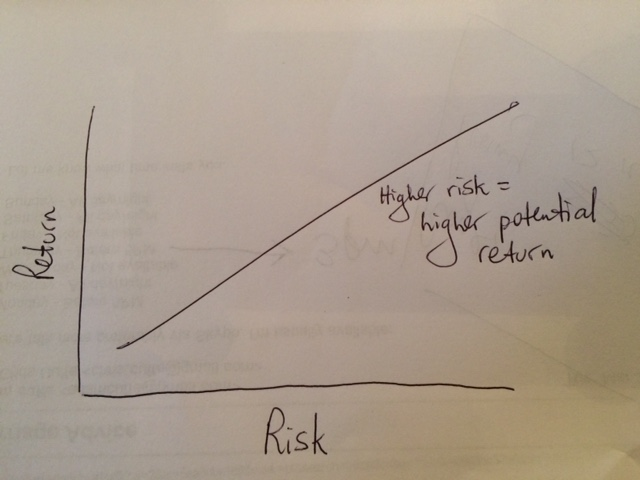

Like many, I think a good and simple way to think about investing is to visualise a line graph with risk on one axis and return on the other and with an arrow pointing from lower left to upper right. It represents the range of possible investment outcomes. This basically depicts the view that the greater the expected return from an investment then the greater the risk. This is a sensible way to think of investing within a framework of no free lunches.

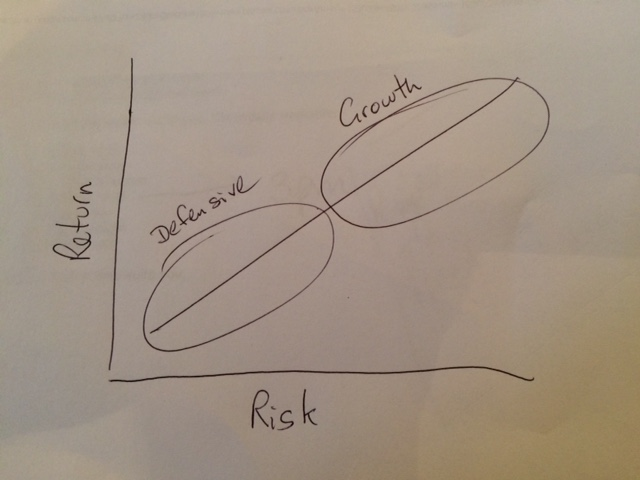

Many investment professionals then segment this risk/return line into two sections. The bottom part comprises ‘defensive’ assets and the top part comprises ‘growth’ assets.

And most think of defensive assets as comprising cash and fixed interest, with growth assets comprising shares and property.

It’s neat, simple and convenient but in my view, these classifications are likely to mislead.

Avoid the word ‘defensive’

The largest option category run by institutional superannuation funds is their Balanced Accumulation option. Such investment products are usually classified as having approximately 30% in defensive assets and 70% in growth assets. And if the manager is feeling bearish about equity markets, they will proclaim that they are increasing their allocation to defensive assets.

The language is wrong. If we must use a two basket classification, then I prefer the terms ‘income’ and ‘growth’ which is a reference to where the majority of the return of a security or asset class is predicted to come from. Generally speaking, assets whose returns are largely from income (on the assumption the income is relatively secure and predicable) are considered less risky than assets whose returns are largely from growth (and hence dependent on many variables, mostly on future prospects).

I dislike the term ‘defensive’ because it is subjective and makes no reference to current valuations, timeframes or investment objectives. Defensive against what? And if I look in the dictionary the word ‘defensive’ has positive and comforting connotations like defending, guarding, safeguarding, protecting and shielding. So if the term is used, we need to be sure we know what we are talking about.

Some simple examples to illustrate the point:

- You will lose a lot of money from holding a 10-year government bond (regarded as a risk-free asset and hence one of the more defensive of all assets) if interest rates move up materially and you are required to sell it before maturity, or if your performance and measurement are judged on a quarterly basis.

- Cash is considered a very defensive asset. But if my investment objective was, say, to achieve a return in excess of CPI over the medium to long term, then cash may be a high risk asset. Many investors who went into cash after the GFC saw their incomes fall significantly, with real returns now below zero. Similarly, holding a portfolio of high quality equities over the long term gives a high probability of beating inflation, and dividends from shares and rents from property usually fall only 20-30% in a recession. But ‘cash’ is usually the lowest risk (and most appropriate) asset if your investment time frame is very short (say less than one year).

- If the spread (margin above a government bond) on the debt of blue chip company is much tighter than the long-term average, then it may be a high-risk investment. Spreads can easily widen in different economic climates with resultant capital losses.

My point here is that hard-wired classifications can be misleading. It’s better to think of defensive as a relative concept, not the absolute that the word implies to most people.

Cash does offer certainty of capital value and immediate liquidity, and those are fine ‘defensive’ qualities, while bonds offer certainty of capital value and interest income if held to maturity (and assuming no defaults).

What do we really mean by ‘risk’?

What does the term ‘risk’ mean when we are trying to look at the risk/return characteristics of a security on the assumption we have a long-term time frame?

Most investment professionals (and non-professionals) equate risk to the degree of volatility in asset prices, usually measured as some variance around a mean return. However, I don’t believe this tells us much at all. In my article titled ‘We need to talk about risk’ I state that, like Howard Marks (a renowned US investment manager and investment author), I think the possibility of a permanent capital loss from owning an asset is at the heart of what investment risk is truly about. Then follows the possibility of an unacceptably low return from holding a particular asset. Marks believes much of risk is subjective, hidden and unquantifiable and is largely a matter of opinion. He makes the point that investment risk is largely invisible before the fact – except perhaps to people with unusual insight – and even after an investment has been exited.

No less an investor than Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s investing partner, said:

“In thinking about risk, we want to identify the thing that investors worry about and thus demand compensation for bearing. I don’t think most investors fear volatility. In fact, I’ve never heard anyone say, ‘The prospective return isn’t high enough to warrant bearing all that volatility.’ What they fear is the possibility of permanent loss.”

I agree with him. Market professionals like the traditional measure of risk, volatility, because they can measure it and sound intelligent. But if I am confident about the long-term prospects of a company, and I plan to hold its shares over the long term, then I don’t care about the short-term volatility. In fact, I try to ignore the share price except when I’m forced to do my accounts.

Like the word ‘defensive’, let’s also be careful how we think about and use the term ‘risk’.

Chris Cuffe is co-founder of Cuffelinks; Portfolio Manager of the charitable trust Third Link Growth Fund; Chairman of UniSuper; and Chairman of Australian Philanthropic Services. The views expressed are his own and they are not personal financial advice.