Residential property constitutes by far the largest asset class in Australia, and on average, property accounts for over two-thirds of Australian households’ net worth. If you include investment in the bank shares, which are themselves heavily exposed to property, the average Australian household has about 70% of its net worth ‘at risk’ exposure to residential property.

What does this mean for the share market?

Various commentators have recently warned that the market valuations of the four major domestic banks are high. But instead of analysing P/E multiples, low credit losses or high payout ratios, in this article we apply a ‘big picture’ outside view of the banks.

Australian banks have been outstanding performers from both a revenue and share price perspective. Currently all four major Australian banks (ANZ, Commonwealth, National Australia Bank, Westpac) are among the largest 14 banks in the world by market capitalisation, which is extraordinary given that no German, French, Italian, or domestic British bank is in that top 14. There is one Japanese bank in the top 14, whereas 25 years ago, when the Japanese property bubble was at its peak, nine out of the top ten banks were Japanese. This is not just a question of market concentration — the entire Japanese banking sector value is 20% less than the big four Australian banks together.

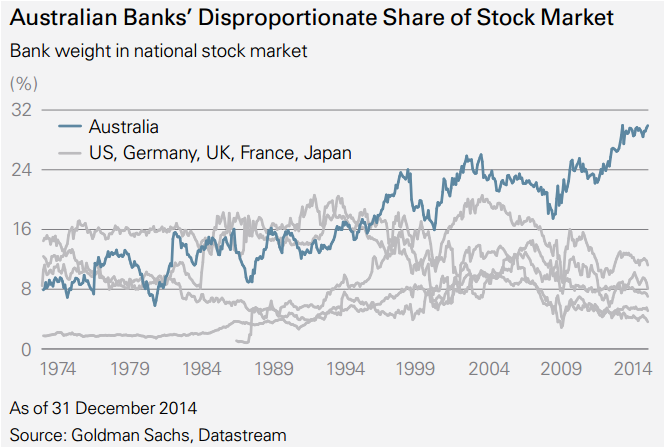

Another useful comparison across countries and history is the size of the banking sector relative to the value of all the other listed companies in (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

The Japanese banking sector accounted for just above 20% of the market at the 1990 peak of the Japanese debt and property bubble. A similar level of 20% was reached by the UK banking sector at the peak of the pre-global financial crisis boom in the 2000s (though this was enhanced by non-domestic banks, such as HSBC and Standard Chartered, being listed in London). The index weight of Australian domestic banks is over 30%, a level not even reached during lending and property bubbles in markets overseas. It seems reasonable that the value of a nation’s (listed) bank sector should bear some relationship to the value of its (listed) national economy. Across the world this ratio is about 1:10; in Australia it is 1:2.

Australian banks do well because there is a lot of debt

Why are Australian banks so highly valued? Put simply, Australian banks earn very high profits. However, this is not because, in our view, they are better run, enjoy better margins, or use more advanced technology, but because there is a lot of debt in Australia. This debt is effectively the top line of a bank’s P&L — the more debt, the more net interest and fee income.

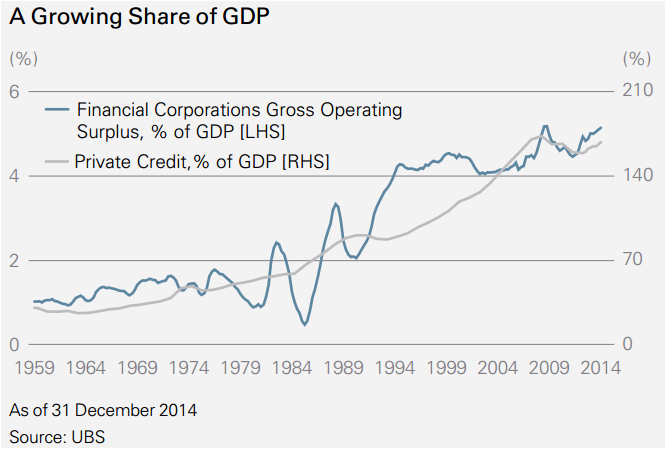

Figure 2:

This relationship is illustrated by Figure 2, which shows financial sector profits (which are dominated by banks) relative to GDP and outstanding credit to GDP. As both quantities are expressed as a percentage of GDP, one might expect a steady ratio. Instead we find that since the late 1950s credit has grown about five fold relative to GDP and so have financial sector profits. In this sense the high valuations of Australian banks have been driven by the same drivers as in the United Kingdom before the global financial crisis, and in Japan before the bust.

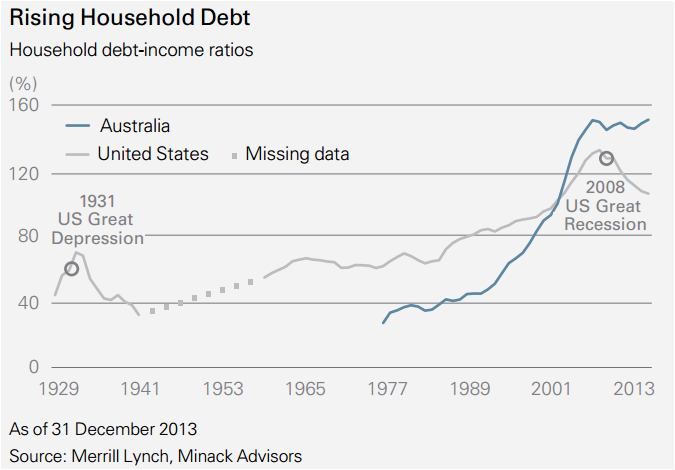

Figure 3:

The household sector has primarily been responsible for this growth in debt, as individuals have increased borrowing to purchase residential property. Figure 3 shows the household debt to income ratio over time for the United States and Australia. We note three features of these developments. Australian household gearing, previously much more conservative than that in the United States, rose very rapidly between 1990 and 2008 and exceeded US debt levels. US households have de-geared since 2008 while Australian households have not, and indeed the latest data show new record highs in Australia. The gap to the United States has thus widened further.

This data is not encouraging, but we note that there have been some positive lessons learned from the US crisis. ‘Low-doc’ lending, which the banks were just ramping up in the lead-up to 2008, seems to have mostly disappeared, liquidity levels at the banks have improved dramatically, and regulators have insisted on them holding significantly more capital. This does help but to what extent, if the lending and speculative investing continue unchecked? One is inevitably reminded of George Santayana’s well-known aphorism that ‘those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it.’

What to do?

These risks are real, in our view, but we do not know when and how these distortions will be remedied. We are more confident that, in a decade hence, this distortion will be obvious, like so many others before it. In the meantime, however, we face difficult choices. Given the uncertainties, and in particular our lack of information about the timing of any adjustment, how can investors sensibly and prudently proceed?

We describe two actions that can be taken within the context of the Australian stock market:

- Investors around the world have sought out stocks with sound yields and defensive earnings, focusing on the utility, infrastructure, health care, and telecommunications sectors. However, in Australia (and only in Australia, it seems), this focus has included banks. Given their gearing and exposure to the domestic economy, we do not subscribe to this local view of banks as defensives.

In our view, however, there are genuine defensives within the Australian market, in the sense that a sharp economic downturn would affect such companies less. These companies may have their own idiosyncratic problems at times, but they can mitigate macro-economic sensitivity within a portfolio. In our view, not all yields are created equal and some are safer than others.

- There are, furthermore, successful Australian companies that have expanded globally and now run competitive businesses offshore or export to other nations. These companies can act as hedges to the Australian residential/bank exposure because a decline in the Australian dollar, lower wage growth, and spare capacity in Australia would raise the value of these companies. We believe the value of these companies would be enhanced in local currency in the event of a recession finally ending Australia’s remarkable run of 24 years without a downturn and its associated 24-year run of increasing household leverage.

In closing, we would like to stress that we are not predicting an imminent crash in Australian property prices. However, investors should be aware of the enormous exposure Australians have to this risk and that property and banks are likely to be highly correlated in any downturn. And while we can’t predict when these market distortions will start to unwind, we suggest that investors consider treating banks less like defensive holdings and consider domestic companies with global exposure in their portfolios.

Dr Philipp Hofflin is a Portfolio Manager at Lazard Asset Management. This article is general information and does not address the personal needs of any individual. This article is an extract from the longer version and is reproduced with permission.