How many times have you heard lately that a ‘1 in 100 year’ event has occurred? Weather and financial market events in particular seem to have occurred far more often in recent times, typically with grave consequences for people’s quality of life.

The Global Financial Crisis was described many ways, ‘a five standard deviation event’, ‘a black swan event’, ‘once in a generation’. But putting odds on this type of event is misleading. It suggests that these are predictable events, which they are not, or that they will not occur for another 100 years. That’s why for all the time finance professionals spend talking about risk, 99% of them failed to forecast the GFC. Too much of the industry looks in the rear vision mirror to assess risks, such as ‘based on the last 100 years of data, the chances of that event happening are 1 in 100’. They define this rear vision probability-based approach as ‘risk’.

But what if past performance is not indicative of future performance? What if the world has fundamentally changed, for example due to climate change, or more leverage being applied by parts of the finance sector? What if the world’s population in the future is much older than the population in the past therefore making past data irrelevant?

Looking backwards to define risks is missing a major part of the current and future risk equation. The other part of the risk equation is ‘uncertainty’.

What is the difference between risk and uncertainty?

Risk is typically defined as the chances of something happening in the future given what we know about the past. Uncertainty is the reality that some outcomes aren’t predictable just by looking at the past.

Frank Knight, a relatively unknown economist from the 1920s, described the difference very elegantly. He was the first economist to break ranks and suggest that assuming certainty was foolish, and that there were two distinct concepts of ‘risk’ and ‘uncertainty’. His assertion was illustrated by imagining an urn containing marbles, 40% of which are red and 60% are not red. If you draw one marble from the urn, you don’t know what colour the marble will be, but you know that there is a 40% risk that it will be red.

The non-red marbles are yellow and black. You don’t know how many there are of each. So when you are about to draw a marble from the urn, if you were asked what the risk is that it will be black, you have no way of really assessing the probability. It’s not 40% or 60%, it is unknowable. That unknowable is what Frank Knight characterised as uncertainty. And there is a big difference between risk and uncertainty.

Uncertainty is the most important consideration in investing

Uncertainty must be considered in planning retirement in particular. Once retired, there is typically little chance of being able to earn back any capital lost. Similarly, there is no chance of stopping your spending while you wait for markets to rebound. You either need to have enough certain income, or you will be forced to sell assets during the storm, which is never a good outcome. Uncertainty, more than risk, poses a significant question for investors: “If no-one can predict the future with any certainty, what can I do to ensure I survive the storm?”

Many investors decide the best way to survive is to simply invest in term deposits and other cash investments. In fact, the average SMSF in Australia today has around 27% of its assets in cash. If we look at ‘risks’, i.e. looking backward, this seems like a safe strategy. Inflation has been between 2 and 3% for nearly a generation and doesn’t appear to be going anywhere any time soon. But what if inflation did spike like it did in the 1970s? How would your retirement funds survive then?

“The asset class that most investors consider the ‘safest’ – cash – is actually extremely risky.” – Warren Buffett

Obviously Buffett has used ‘extremely risky’ for effect. Cash isn’t extremely risky. But it’s not risk free either, and the risk is inflation. It is not anticipated inflation (2-3% pa), it is the unanticipated inflation that is damaging. What is hard is thinking about how inflation could possibly jump to say 5% or more when it has been so benign for so long.

Investors in 1970 probably felt exactly the same. At that stage, they had seen 18 years of inflation averaging 2-3%. But retirees in 1970 would see 76% of their savings eroded by inflation over the following 13 years (their life expectancy at that time). Economists in 1970 were saying there was a ‘minor risk of inflation’. But uncertainty was about to impact retirees like never before.

Inflation risk and inflation uncertainty

Most economists aren’t predicting a jump in inflation now either, and nor are we. Our expectation is that inflation can be contained in the 2-3% range, with some risk on the upside if the fall in the AUD pushes up import prices. We can point to that risk because in the past a falling AUD has led to inflation pressures, such as due to rising petrol prices.

But there is a new uncertainty at play at the moment, quantitative easing. Will global inflation spike as a result of the cheap credit that central banks in the US and EU are providing? Five years or more of pumping cheap credit into financial institutions and the economy is unprecedented. Just like predicting the chances of pulling a yellow marble out of the urn, we don’t have any data to use to predict what impact this will have on inflation in the next 10 years. This is ‘unknowable’ because there is not much more than academic theories to guide us.

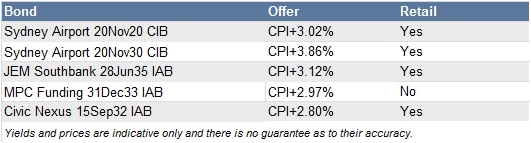

That unknowable risk is what Frank Knight characterised as uncertainty. Given that it is unknowable, all you can do is to consider whether you want to include investments in your portfolio that rise in value and/or increase income if inflation does suddenly jump. Gold, oil, farmland, infrastructure and inflation-linked bonds are historically amongst the best inflation hedges (i.e. investments that will go up in value if inflation rises). Australian investors have plenty of options for investing in these assets with many on the ASX, but also through the unlisted bond market. We've listed a few examples below:

Craig Swanger is Head of Markets at FIIG Securities. To learn more Corporate Bonds click here. This article is for general education purposes only and is not personal financial advice.