Share prices around the world have divided sharply since the advent of COVID-19, with some on-line businesses rocketing in value while more traditional businesses are struggling to regain earlier lustre. Are the on-line darlings massively over-priced or are some of those currently in the doldrums significantly under-valued?

The impact of low rates on share values

Adding to the debate are arguments that the elevated valuations are justified because the cost of capital is at historically low levels. In share valuing terminology, as discount rates are lower, 'terminal value' multiples should be much higher.

The following is a brief explanation of a standard discounted cash flow model and why the assumptions used can generate massive variability in share value outcomes.

The underlying principle is that the current price of a share is the sum of all future net profits of the business, divided by the number of shares on issue, discounted by the estimated cost of capital of that business. Valuation models are constructed on forecasts of the estimated profits of the business for the next 5-10 years, followed by an estimate of the so-called terminal value of the business (ie summing the balance of sustainable growth in profits to eternity discounted back to that date). Usually, this terminal value represents at least 60% of the estimated value of the business and is much higher for high growth start-ups.

Estimating what discount rate should apply starts with the assumption that the current long term government bond yield is the so-called risk-free rate and margins are added for:

- the estimated relative riskiness of the industry in which the company is operating

- the expected volatility of company performance through economic cycles (beta), and

- the likely debt gearing the company will aim to operate with

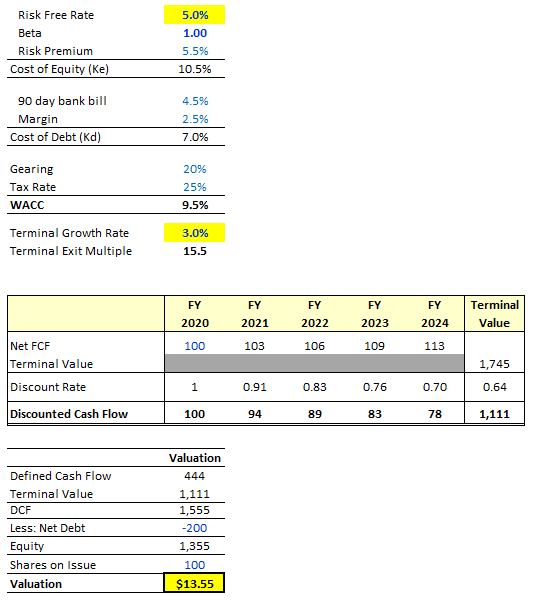

In the tables below, we have used a risk premium of 5.5%, a beta of 1 and 20% as a 'standard' industrial company gearing ratio, producing a weighted average cost of capital of 9.5%.

High growth rates and low interest rates are incompatible

It is our contention that many current valuations are assuming that real economic growth rates will resume back to what they were when interest rates were significantly higher. The fact that interest rates are close to zero right along the bond curve indicates that neither the market or central banks believe this to be the case. As such, these lower growth rates also need to be reflected in valuations to ensure a sensible outcome.

Working through the mechanics of a simple DCF we can see how these distortions play out.

We start with an 'old' set of assumptions whereby the risk-free rate is set at 5% and the terminal growth in net profits rate at 3% pa. This leads to a terminal value multiple of 15.5x and a notional valuation of $13.55 for our theoretical company.

What happens when we collapse the discount rate and keep all else equal?

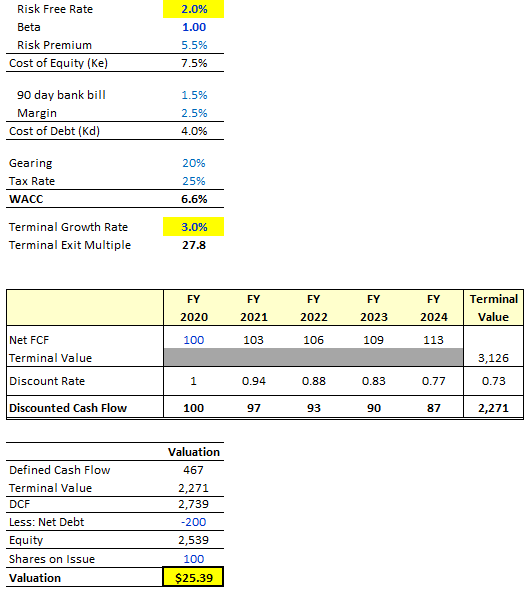

Taking the risk-free rate down to 2% leads to the terminal value multiple increasing to 27.8x and the valuation for our theoretical company rising 87% to $25.39. Financial alchemy at its finest!

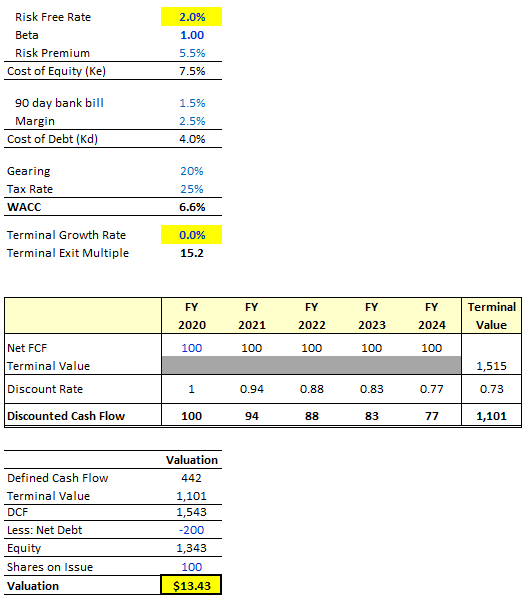

But now let’s reflect the lower growth rate implied by the lower risk-free rate. Central banks around the world aren’t setting short-term funding costs at 0% and below because the outlook is rosy. Taking the growth rate down to reflect an environment that justifies a lower risk-free rate lands us approximately back where we started in valuation terms.

Need a meaningful link between rates and growth

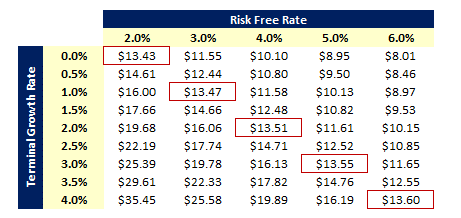

These workings highlight how critical not only the setting of the risk-free rate and the terminal growth assumption are in deriving the DCF, but in ensuring that there is a sensible linkage between them.

For our theoretical company, the table below demonstrates how a valuation can be completely overpowered by these two key assumptions; assumptions that tend to get far less attention than the detailed work that goes into deriving the cash flows of the business.

Even in secular growth companies, a recognition of the lower growth outcomes associated with a lower discount rate is essential. Apple will still sell lots of phones, Amazon lots of products and Google lots of advertising but not as much as they would have in a world that justified a higher risk-free rate.

And it is in high growth companies that the impact becomes even more pronounced. Given the lack of profits in the short term for some high growth companies (think Tesla, Netflix or even our own Afterpay) a lower discount rate provides greater weight to the distant future cash flows while also pushing an even greater proportion of the valuation into the terminal value. In these high growth companies, upwards of 90% of the valuation can sit within this terminal value.

Valuations must focus on more than cash flows

There have been many instances throughout my investment career where cash flows have broadly aligned with sell-side assumptions but the resultant company valuations have differed wildly. The explanation invariably comes down to the set of assumptions and linkages (or lack therefore) between the risk-free rate and the terminal growth rate.

My first question when comparing company valuations moved from “what are your assumed through cycle cash flows” to “what discount rate and terminal growth rate are you using” because that was where the bulk of the valuation dispersion was hidden. But in finance, as in life, if things appear too good to be true they invariably are.

The magical value creation through lowering discount rates while assuming growth is untouched is one such example that falls into this category.

Trent Masters is the Founder and CIO of Global Evolution Capital, a global absolute return fund shaped around key industrial evolutions. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.