Italy’s 66th post-war government collapsed in January 2021 when a coalition led by Prime Minister, Giuseppe Conte, crumbled. President Sergio Mattarella encouraged the parties to revive the alliance so he could avoid calling a snap general election during a pandemic.

But the talks failed. As concerns grew that any election might usher right-wing populists into power, Mattarella pulled off a masterstroke. He unexpectedly contacted Mario Draghi; yes, ‘Super Mario’ who saved the euro in 2012 with his ‘whatever it takes’ comment. Mattarella asked the Chief of the European Central Bank to form a ‘national unity’ government. Within days, Draghi become Italy’s 29th prime minister since 1946.

The bellwether of European risks

Investors were pleased. On 13 February, when Draghi became Italy’s fourth unelected premier since 1993, the ‘lo spread’ – the yield at which Italian 10-year government bonds trade over their German equivalents, a number that is judged the bellwether of EU economic and political risks – had narrowed to a five-year low of just under 1% (100 basis points).

Draghi’s government retains the confidence of investors yet the lo spread has widened to 200 basis points. What malfunction occurred that widened the gap towards the 300 basis-point level that is seen by many as the tripwire for a crisis?

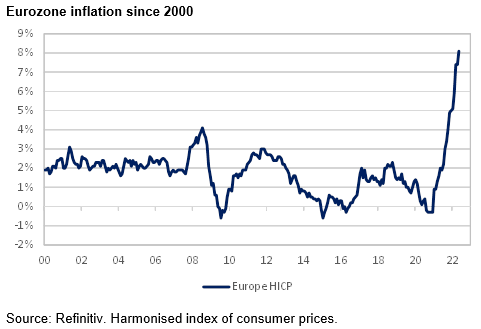

The culprit, like elsewhere in the world, is inflation. Eurozone consumer prices surged a record 7.4% in the 12 months to April 2022 due to promiscuous monetary and fiscal policies, rising energy prices, pandemic-related supply blockages and Ukraine-war related disruptions.

The ECB has one objective; to maintain price stability, which is interpreted as keeping inflation below 2%. The central bank has little choice but to tighten monetary policy by raising rates and ending its asset buying.

Rising rates bring more worries

Many central banks are doing likewise to tame inflation. For most countries, the main threat is the resultant slowing in economic growth boosts the jobless rate to worrying levels if economies slump into recession.

For the eurozone, the ramifications of tighter monetary policy are more concerning for three reasons.

The first is the ECB is poised to stop acting as the buyer of last resort for its almost-bankrupt ‘Club Med’ members such as Italy, where gross government debt stood at 151% of GDP at the end of 2021. That cessation could trigger a bond sell-off that puts the finances of debt-heavy governments on an unsustainable footing. National government and commercial lenders holding their government’s debt might become entwined in a downward spiral. The ECB would be exposed as lacking any credible way to quell such a government-bank suicide bind.

The second problem with tighter monetary policy is the resultant downturn will remind indebted euro-users that they have no independent monetary policy to help their economies, nor a bespoke currency they can endlessly print to meet debt repayments or devalue to export their way out of trouble. The only macro tool domestic policymakers possess is fiscal policy but that is maxed out. Populist Italian politicians are bound to talk of readopting the lira.

The third means by which higher inflation is poisonous is it creates a fissure between the area’s creditor and debtor nations that would make it harder to find durable solutions for the euro. Inflation-phobic but inflation-ridden Germany and other creditor countries will battle with debt-heavy France (government debt at 113% of GDP), Greece (193%), Italy, Portugal (127%) and Spain (118%) over how far the ECB should go to rein in inflation and how it might help the strugglers.

To maintain its inflation-fighting credentials, the ECB must tame inflation even if that stance crushes economic growth. The core concern of such tight monetary policy is that it would expose how the euro’s flawed structure – that it is a currency union without the necessary political, fiscal or banking unions – has become explosive due to the large debts of southern eurozone governments.

Whither Europe?

To be sure, policymakers are likely to once again thrash out some last-minute fudge that defers a denouement on the euro’s fate. But temporary solutions are only, well, temporary and the euro needs a durable resolution. The indebted south could win the political tussle such that the ECB never makes a serious attempt to tame inflation. But that path might only delay tighter monetary policy and subsequent detonations. The cost of servicing public debt, while rising, is still historically low, which reduces the likelihood of missed debt payments and a crisis.

Eurozone governments are restarting efforts to create a proper banking union but success is not assured. The lo spread is well short of the post-euro record 556 basis points it reached in 2011 during the eurozone crisis that was triggered by the current-account imbalances among members. But Rome’s debt was only 120% of GDP then, and that gap narrowed only due to ECB support that is now waning because the problem today is inflation.

Germany’s economic slump and dislike of inflation will ensure Berlin pressures the ECB to prioritise inflation. The lo spread could widen enough to threaten a flawed currency union, especially if member countries are squabbling over solutions. While Draghi ‘the central banker’ could bluff investors, Draghi ‘the politician’ has no similar obvious masterstroke. To all the world’s problems, be prepared to add elevated doubt about the euro’s long-term future.

Michael Collins is an Investment Specialist at Magellan Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is for general information purposes only, not investment advice. For the full version of this article and to view sources, go to: https://www.magellangroup.com.au/insights/.

For more articles and papers from Magellan, please click here.