Australia enters 2026 with its three largest cities each having an average house price of over $1 million. It’s frustrating for young Aussies like me looking to buy their first home. But it’s also the unsurprising outcome of a persistent, decades-long myth: that falling house prices are electorally fatal.

Prime Minister John Howard set the tone in 2003, when he dismissed rapidly rising prices, quipping that no one complained to him about their home gaining value. Housing Minister Clare O’Neill repeated the same sentiment before the last election, promising “sustainable growth” in house prices.

Both parties have, as a result, repeatedly put their faith in announcement-friendly demand-side subsidies, like first home-owner grants and shared equity schemes. These counterproductive schemes are the result of a political straightjacket that’s shackled housing policy for most of my life: record high prices are locking out young people, but any hint of falling values seemingly terrifies homeowners.

That fear, though understandable, is misplaced.

The economics of property have quietly shifted over the last year. Thanks to mass-upzoning by state governments, our housing market is no longer limited to allocating quarter-acre blocks. Now, it’s about considering the new value that can be created on each block. This may frustrate some NIMBYs who fret about preserving their suburbs’ “unique character”, but it’s the emerging paradigm that’s, thankfully, taken over Australian urban policy.

This new paradigm enables increasing prosperity to exist alongside falling prices. When one $3 million house is replaced by four $1 million apartments, the average price on that lot drops by two-thirds. But, the total value of housing rises by a million. The seller walks away with a windfall gain, and three new families gain a foothold in the market. Put simply: existing land being used more efficiently delivers us more affordability.

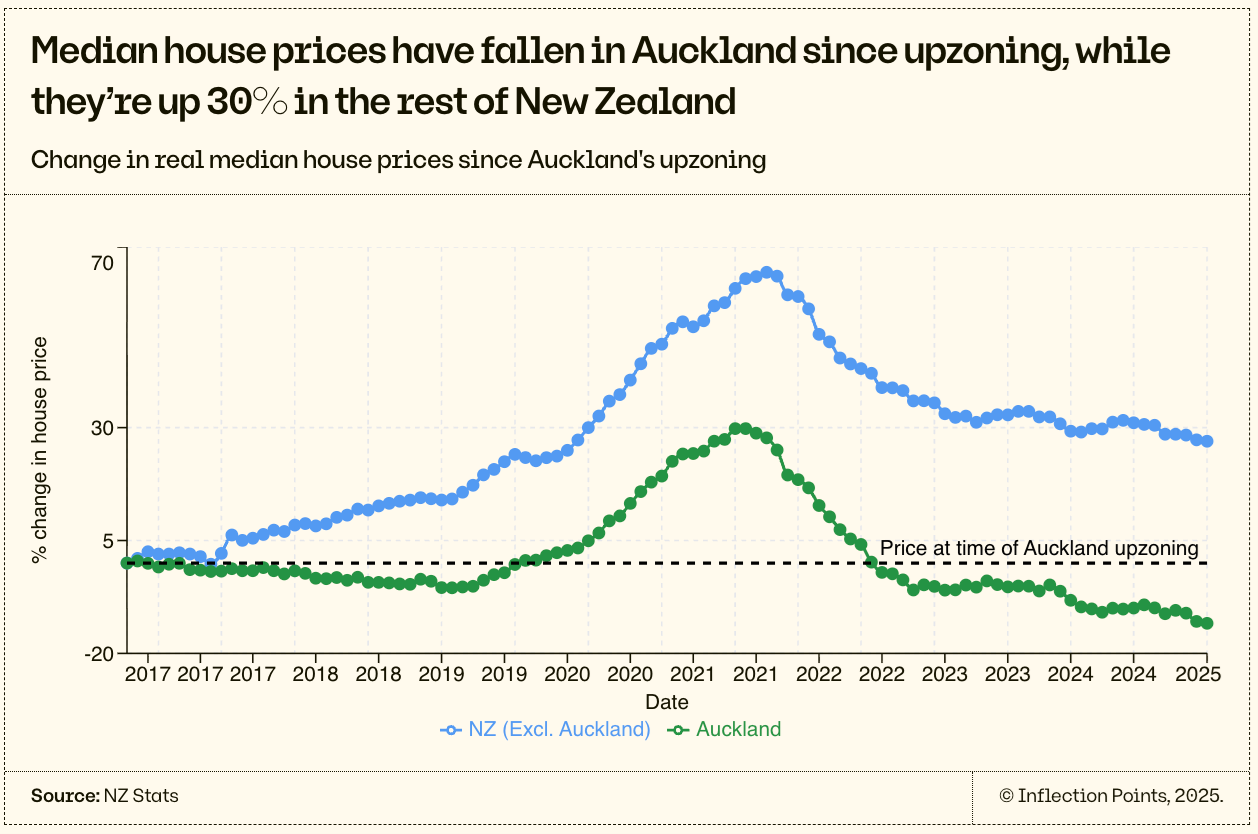

Scaled across a city, that delivers more homes, lowers prices and increases aggregate wealth. We’ve seen that very dynamic play out in Auckland, whose prices fell 13% relative to other kiwi cities as new construction boomed. Replacing just a small fraction of Australia’s detached houses with apartments could unlock billions in housing wealth.

Of course, part of this value will be captured by developers, and there are genuine constraints on how rapidly we can expand supply (like, for example, construction sector capacity). While there will be some spillover that will lower the prices of existing homes, this could be more than offset by more dwellings.

Importantly, these falling prices shouldn’t be as daunting as they seem. Housing wealth largely stays within a closed system: when someone sells their home, the proceeds are typically spent on buying another. When one home sells for less, the next one they buy also costs less. While seniors downsizing into cheaper homes will take a hit, our generous superannuation system should be more than enough for their retirement.

In the end, most owner-occupiers never realise their illusory paper gains. Instead, they hold onto their homes until they die, leaving the proceeds to their estate. That might be a trade-off that some parents are willing to make for their children. But it’s a decision that all too often drives those very same kids out of their home cities and delays grandchildren.

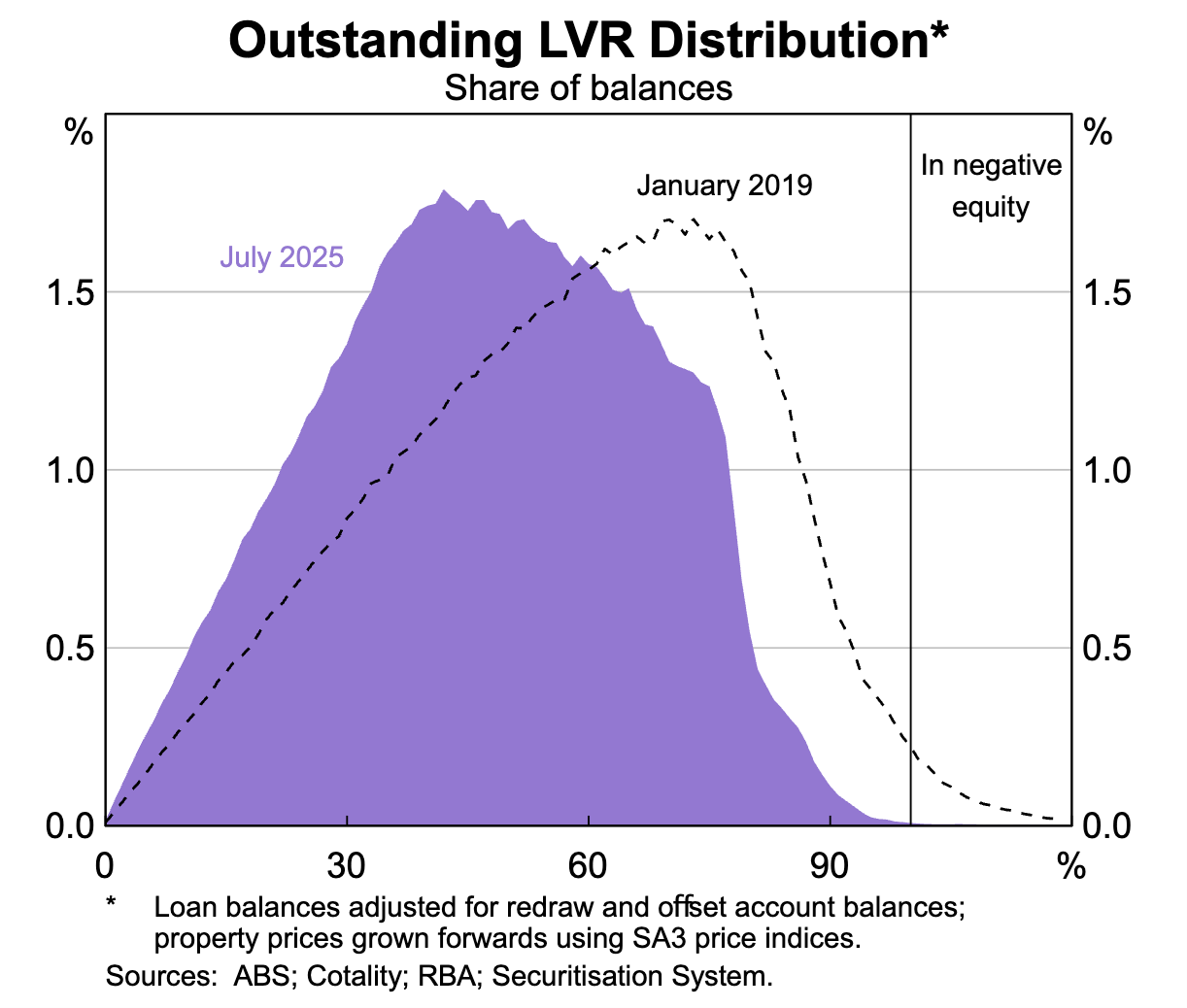

The bigger concern is the financial system, as banks’ balance sheets are built on property. But, because most loans are well above water a moderate correction wouldn’t sink the system. That’s because of our steel-clad financial regulations, which ensure banks have large serviceability buffers and strong balance sheets.

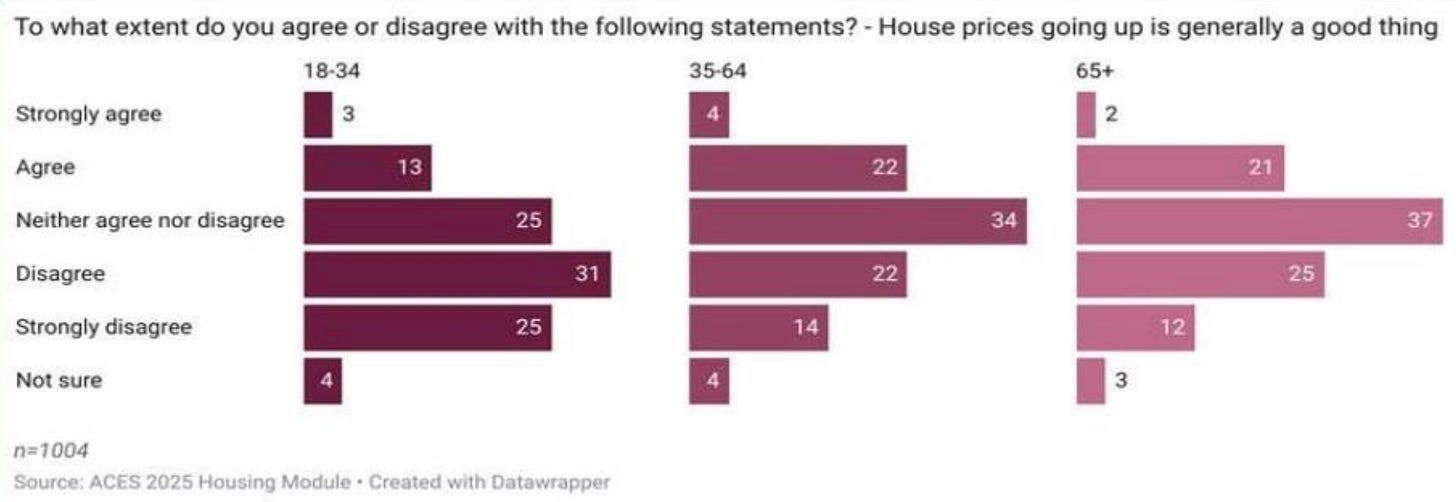

But I’m optimistic. In what might shock nervous political staffers, less than a quarter of boomers believe that rising house prices are a good thing. Andrew Bragg’s recent call for the 'Death of NIMBYism' has departed from the historical script. And Grattan Institute modelling shows that, with the right policies, we could shave $100,000 off the average home.

While state and federal governments have taken steps in the right direction, more can be done. They should scrap minimum floor-space ratios, which make it uneconomical to densify smaller plots of land. They should follow New Zealand’s lead by more aggressively upzoning parts of our cities. They should stop delivering counterproductive demand-side schemes. And they should help consolidate our fragmented construction sector to boost its productivity, which has gone backwards since the 1990s.

Few people stopped to talk about housing with John Howard as he strolled around Kirribilli in his green and gold tracksuit in the early 2000s. Back then, our housing crisis felt manageable. Today, as Sydney edges toward becoming a city without grandchildren, these same neighbors might have a few choice words.

Australia’s housing market can be both fair and prosperous, but only if we stop treating housing affordability as a zero-sum game. The real political poison would be pretending, for yet another generation, that we can have affordable homes without prices falling.

Manning Clifford is the editor of Inflection Points, home of long-form Australian policy writing, focusing on housing policy, financial regulation, institutional reform and community building. This article is reproduced with permission from Manning’s Substack blog Inflection Points.