From day to day, we are barely conscious of our own ageing, never mind the long term trends in Australia or the world. You might receive a sudden jolt when you see an old friend after a 30 year absence, all wrinkles and paunch, and wonder if you have also changed as much. Or you look back and realise you’ve had the same job for 30 years, or lived in the same house for 20.

The one time we all consider the passing and future decades is when we approach retirement, and think about how long our money needs to last. However, we cannot plan our own financial outlook without considering an economic or global context. For example, if we retired at a time when the number of retirees was small in proportion to workers (the so-called ‘dependency ratio’), then we could be more confident that rising tax revenues and economic growth would support age pensions, health systems and public transport. Notwithstanding the introduction of compulsory superannuation over 20 years ago, the majority of Australians will continue to access at least part of the age pension, and this reassurance about future services is crucial for their retirement plans.

But what if that low dependency ratio is in the past? In recent weeks, Treasurer Joe Hockey and other Federal Government ministers have made it clear that the budget deficit cannot be allowed to blow out to sustain the levels of support traditionally provided. We have a pension system which exempts the family home, and a couple sitting in a multimillion dollar house with $1 million in other assets and annual income of $60,000 can draw a part pension with all the associated health benefits (hearing aid cost $5,000, supplied for free, come back for another next year). The current debate on increasing the pension age from 65 to 70 is scratching the surface on likely changes.

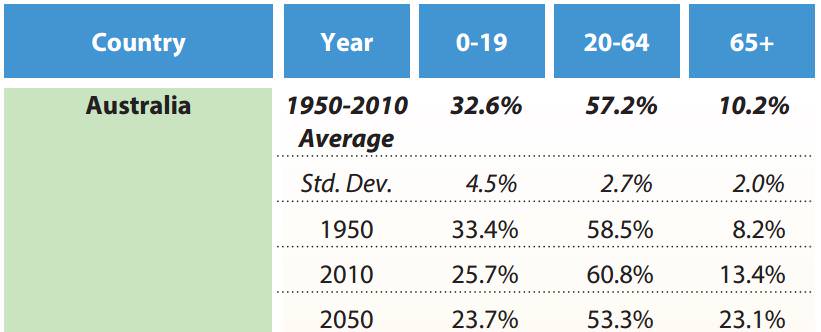

Consider the following table, showing the proportion of the Australian population in each age group: the younger people up to 19 years of age; the large bulk of the working population from 20 to 64; and the older people (currently pension age) of 65 years and older.

Source: Journal of Indexes, September/October 2013, ‘A New ‘New Normal’ In Demography and Economic Growth’, by Robert Arnott and Denis Chaves, page 25.

In 1950, only 8.2% of the population was over 65, but by 2050, it is expected to reach 23%. At the moment, two-thirds of people aged 65 to 69 are retired. For a person aged 65 expecting to live at least another 20 years, the majority of their remaining years will involve some level of disability or dependency. The costs of such services in Australia are a massive drain on public resources, as well as the age pension. There’s no doubt future entitlements will reduce, and we need to focus on the demographic changes that are coming, and not think as 2030 or 2040 as the never-never.

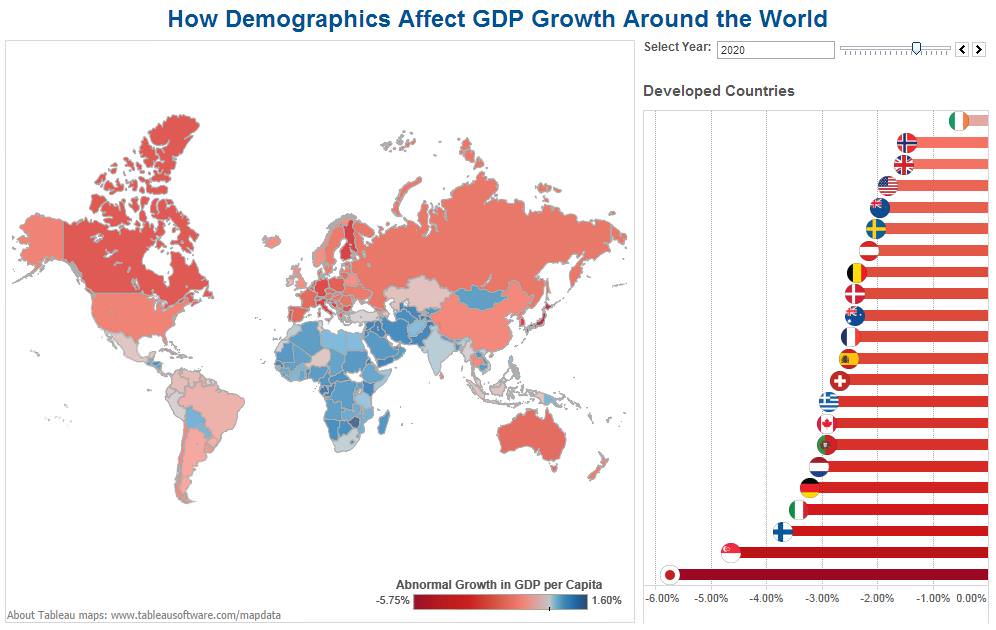

The Californian research and investment strategy company, Research Affiliates, has produced interactive maps which show the likely effect of demographic change on GDP for major countries around the world, including Australia. In addition, Robert Arnott and Denis Chaves have written extensively on the economic and social implications of these changes, as shown in the following article.

The first ‘infographic’, linked here, allows the user to select the year by moving the tab in the top right corner, and see the effect on GDP growth of demographic change in that country. For example, the figure below shows the year 2020.

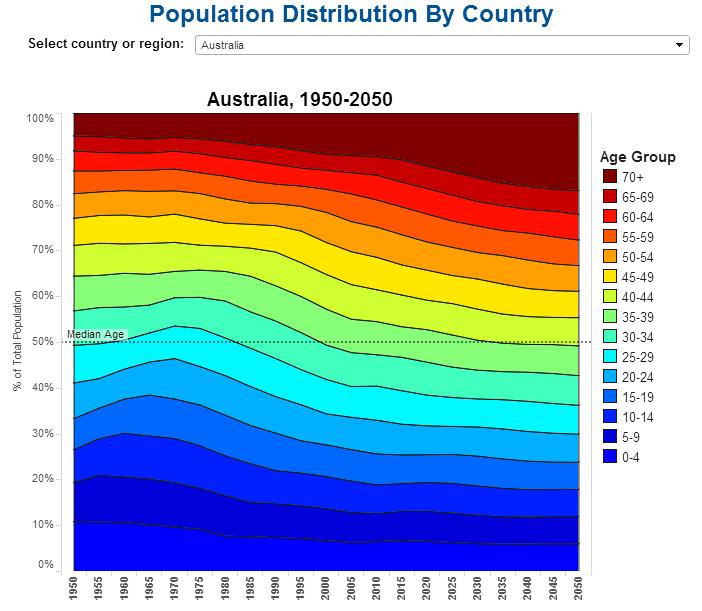

The second ‘infographic’, linked here, shows population distribution by country, with Australia shown below. The most notable increase is in the 70+ age group, accompanied by a rapidly rising median age.

Introduction to the Arnott and Chaves paper

This is background to the following paper by Rob Arnott and Denis Chaves of Research Affiliates. They argue there is a disconnect between what we take for granted given our recent experiences and what we should anticipate given simple arithmetic. We are not automatically entitled to fast-growing prosperity and ongoing high growth.

In recent decades, we have been blessed by the favourable demographics of a younger, more productive workforce which provided a growth tailwind. The reversal towards an older population will create more of a headwind, and our policies cannot simply spend our way out of trouble for as long as it takes. How we manage the transition will determine the quality of retirement for the majority of Australians.

(Note that the infographic reflects changes between demographics and GDP per capita growth based on the percentage size of each age group. This method results in more extreme forecasts as the size of each age group, especially retirees, continues to grow, while the following article uses an average of two methods that results in a smoother result).