Accounting losses from a pandemic inspired bond buying spree has wiped out the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) equity and more, pushing its balance sheet into negative equity territory.

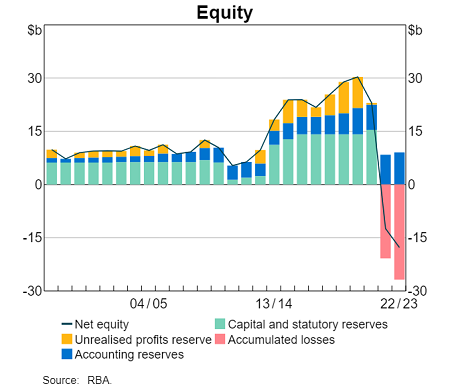

Its 2022/23 annual report shows a loss of $6 billon for the financial year, which following the $36.7 billion loss in the previous year, now has the bank’s liabilities $17.7 billion in excess of its assets (see chart). But being a government entity that can create money to pay its bills, it remains secure.

How it happened

How did the RBA get into this predicament? To understand why the RBA is losing money, we need to follow the flow of money building up to the losses.

When the pandemic exploded in early 2020, the federal government commenced fiscal support packages such as JobKeeper, raising government debt significantly. At the same time, the RBA introduced unprecedented monetary stimulus including ultra-low interest rates and increased commercial bank reserves via quantitative easing (QE).

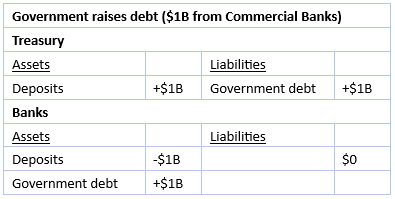

When the federal government raises debt, it is a loan to the government from the private sector via commercial banks. The banks transfer deposits to Treasury, and a matching liability of government debt arises. That debt is recorded as an asset for the banks, offset by the loaned funds it transferred to Treasury. Treasury pays interest on the government debt to the banks. The resulting balance sheet movements are depicted:

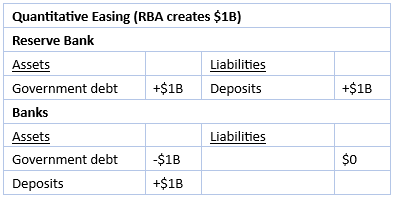

When QE occurs, it is mostly seen as money creation. But it could also be construed as a loan, this time from the private sector to the RBA. Being the “borrower", the RBA gains an asset and a liability, in the form of government debt and commercial bank deposits respectively. The deposits having been created electronically by the RBA, which only central banks can do. The RBA pays interest on those deposits to the banks. Again, the balance sheet movements:

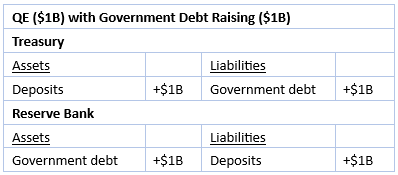

When QE and government debt raising occurs simultaneously, the commercial banks' balance sheets net out, leaving:

If Treasury then transfers its deposits to the private sector to fund say a JobKeeper scheme, then the RBA will have effectively financed that fiscal spending via electronically created deposits. That financing will remain in place until such time that the RBA pays back the government debt it “borrowed” from the banks, and its self-created liabilities are extinguished.

The impact of interest rate rises

The illustrative RBA balance sheet built above reveals a double whammy when interest rates rise. On the assets side, the value of the debt it holds falls with rising interest rates. And on the liabilities side, higher interest rates translate into higher servicing costs on the commercial bank deposits created in the QE process.

With the RBA purchasing some $330 billion worth of government bonds during the QE program at a coupon of around just 0.25%, a rapid rise to 4.1% in the official cash rate has wreaked havoc on the mark-to-market value of its portfolio. And what began as a cost of just 0.1% on the increased bank deposits, has blown out substantially with 4.1% now being paid.

With less than ten per cent of its bonds holdings having matured thus far, the RBA at this stage does not plan to actively sell bonds to wind down its portfolio faster, which would realise capital losses. All the while recognising the risk of further losses if interest rates continue to rise.

This situation is not confined to Australia, with central banks in other advanced economies suffering extensive losses with their QE programs.

The lessons

The question might therefore be asked, did central banks go into the QE caper with eyes wide shut, given the poor financial outcomes of high inflation, rapidly increasing interest rates, and impaired central bank balance sheets?

Many would say that losses should have been expected when buying low-yielding bonds, and when interest rates can really go only one way, up. And that it was not such a good idea after all. While others would say that the stimulus kept businesses afloat, unemployment low, and that it was all for the greater economic good.

In the fullness of time, governments will need to balance whether significant monetary stimulus is appropriate in times of global turmoil, being mindful that there really is no such thing as a free lunch.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.