Tariff wars, emerging markets in crisis, and the US economy overheating … where does one start when trying to work out what it all means?

Well, as always I like to start with history. Have we seen this before? Pretty much. We have many historical examples to ponder, and so many possibilities, but for me the 1960s and the 1990s come to mind.

Let’s start with tariffs. Is it simply brinkmanship, where Trump’s true desire at the end of the day is to force the Chinese to lower tariffs? Or is it something more pernicious, perhaps a multi-decade turning point in globalisation?

If brinkmanship, how will it end? The market assumes rather gently, with the US stock market generally happy to look through the shenanigans and assume a positive end result. Perhaps that will be the case, but key to securing large concessions through brinkmanship is not only threatening large repercussions, as Trump is currently doing, but convincing your combatant that you are deadly serious about following through. More often than not, deadly serious means actually following through.

Kennedy knew this. For a perspective on successful brinkmanship, one can’t go past 13 days in October, 1962 – the Cuban missile crisis. In August 1962, the Soviet Union snuck nuclear missiles into Cuba (in response to the US placing nuclear missiles in Turkey three months earlier) and assembled launch pads before the US noticed. Despite some suspicions, the US did not realise that a nuclear arsenal had been deployed until 14 October when aerial reconnaissance confirmed launch pads and missiles ready to go in Cuba.

Kennedy threatened to invade if they were not removed. The Soviet Union protested. The missiles in Cuba were purely for Cuba’s defence, and any invasion by the US of Cuba would trigger a war with the Soviet Union. Kennedy publicly moved to DEFCON 2 and said that the United States will:

" ... regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response against the Soviet Union."

After some rather tense exchanges, they took his threat seriously, and agreed to remove the missiles. Pretty heavy brinkmanship when the consequences of escalation were so high for both parties. See: http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/history/cold-war/cuban-missile-crisis/timeline.htm

Of course we are not talking about the same consequences here. But we are talking about the same game, namely the game of brinkmanship. To get big concessions, big threats need to be made convincingly. Which as we are seeing, needs some follow through. Sometimes the outcomes aren’t as intended. Beyond brinkmanship, there are a few other examples that come to mind.

Perhaps inflation breaking out, like in the late 1960s when the Fed allowed unemployment to breach new lows? Or can the US economy handle stronger growth, like the productivity surge Greenspan embraced in 1996-97 to forestall rate hikes? Or does none of this matter, because we are about to repeat an EM crisis like 1997-98? Perhaps there is no historical analogue? After all, we don’t have a historical analogue of 10 years of zero to negative interest rates in the major economies of the world, combined with 18 trillion dollars of bond purchases by their central banks! (But we do have analogues of low interest rates generating financial bubbles) Do you have a conviction? If you are highly convicted, perhaps you should heed Alexander Pope’s famous phrase, “A little knowledge is a dangerous thing”! Nonetheless, I think one can have conviction in how scenarios might play out. So let’s start with the scenarios.

The scenarios

1. Tariff escalation. If Trump imposes a tariff of 25% on US$200 billion of US imports from China, and particularly if he follows it up with another US$267 billion of tariffs, that is all that will matter for markets in the next 6 months. With the latter, one can’t escape both a significant growth and inflation impact in coming months. EM equities will fall a further 10-15%, and US equities will likely fall 5-10%. The USD would soar 5-10%, at which point the Fed stops hiking.

2. Tariff de-escalation. If the US agrees a resolution with China, the focus turns back to the current status of the US economy. It is too strong. Initially equities rally, the USD likely falls as emerging market equities outperform, and bond yields rise markedly. At some point in the next 6-12 months the market realises the Fed needs to take a restrictive policy to slow the economy and quell inflation, and a recession gets priced in.

3. A bubble bursts. What bubble? As I wrote in June, after 10 years of zero interest rates and low bond yields, money has poured into any bonds that give a little extra yield. We have seen the wobbles already.

At the moment, with the unresolved tariff war, it is impossible to be emphatic. But the time is nigh when it will pay to be very decisive indeed. And conversely, a disaster, potentially, if you are not.

Am I being too alarmist? Or even too simple? Let me give you some facts, after which you can decide.

How bad can a tariff war be?

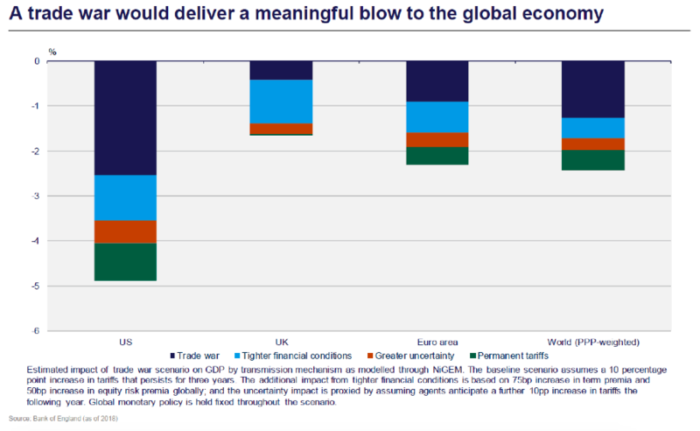

Well I could start with the Bank of England’s prognosis:

Wow, 5% off US growth …

However, note there are some pretty dire assumptions in there. Firstly, they assume every country imposes a 10% tariff. The impact of that is shown in the dark blue (about half the overall impact). The rest of the impact comes predominantly from higher bond yields, lower equity markets, and greater uncertainty. There is no assumption of stimulus, either from rate cuts or fiscal policy (which has just had a windfall from the tariff ‘tax’).

So it is fair to say that the impact would be much less than this. But how much? Well the first point is we don’t know what the final tariffs are yet. But if Trump proceeds with tariffs on all Chinese imports (about $500 billion), as he is threatening, reasonable estimates would see a growth impact of 1-2% for each economy. And that will hurt.

Of course, many assume this is nothing more than brinkmanship. A game of chicken. As John Cirace argues, to win the game of chicken, the individual must “create the impression that nobody is crazier or badder than me”. [Law, Economics and Game Theory. John Cirace, page 120]. Ipso facto, Trump will win!

Or crash ... I’m not sure he realises crashing is a possibility. So he just might not see it coming. What does a crash look like? US stocks down 10%. That would get his attention, though not necessarily a reaction.

Will it happen? Well, by the time you are reading this, the answer might be clear. But I strongly believe as I write, one cannot hold a view on the evolution of the confrontation with conviction. We pay many consultants who are experts on Chinese and US politics. The more you know, you realise the less you can be sure.

Brett Gillespie is Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital and has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. This article is for general purposes and has been prepared without taking account your objectives, financial situation or needs.