Last December, the Federal Government discarded its oft-repeated promise of delivering a budget surplus this year. In April, it ’fessed up to the deficit being a big one. And instead of a run of surpluses as our economy returns to good health, we’re now told we’ll ‘fail our future’ if we don’t run budget deficits for a while. The Government is only beginning to tell us how grim the budget outlook really is. The risk is that we’ll run a substantial budget deficit over the whole cycle in varying economic conditions.

It’s timely to consider what this abrupt switch in fiscal strategy might mean for the economy and for investors, particularly those planning for, or already in, their retirement years.

The long-held promise of a budget surplus

The promise of a budget surplus in the financial year that’s now ending was made back in 2010. The Government wanted to reassure voters that the large budget deficits it would be running during the global financial crisis would soon be wound back and reversed; there’d not be a sustained build up in government debt. Also, the Cabinet had wanted a way of restraining some of their big spending colleagues and backbenchers (older readers might recall the ‘trilogy’ adopted by the Hawke-Keating government to impose fiscal discipline).

On many occasions, the Gillard Government took the commitment to deliver a budget surplus too far, arguing the surplus would be delivered ‘come hell or high water’ and Australia running a budget surplus this year would stand as ‘one of the eight economic wonders of the modern world’.

The deterioration in the budget numbers

The deterioration in the budget numbers for the current financial year mainly reflects the fact that the Government and Treasury have now moved to more realistic numbers for tax revenues, replacing the highly optimistic numbers they’d earlier employed both for the current financial year and for the forward estimates.

Also, the Government is committing to, but is only partly funding, significant new spending programs such as the Gonski reforms to schools policies and DisabilityCare (formerly called National Disability Insurance Scheme). There’s no doubting these policies’ appeal and there’s a good deal of bi-partisan support for them. But they will have to be paid for one way or another.

Government revenues from income taxes haven’t collapsed. Instead – and has been apparent for some time - growth in tax revenues has slowed because of modest growth in nominal incomes. However, from the start, projected revenues from two new taxes had been fancifully high.

The Minerals Resource Rental Tax, which the Government rushed through in 2010 after the debacle of the Resources Super Profits Tax, included revenue forecasts based on commodity prices that, though never made public, were extremely ambitious. They must have assumed that prices for coal and iron ore would stay near record highs for three or four years.

Forecasts for receipts from the carbon tax were built on expectations of a carbon price of $29 a tonne in 2015 – and were not downgraded even when Australia first tied its carbon price to the European price, which was always likely to be weak because of the over-supply of permits and sluggish economies there. The amended forecast is a carbon price of $15 in 2015 (still more than three times the current European price).

Why the structural deficit or surplus is important

Both major parties have long expressed the view – shared, I think, by a majority of voters – that the budget should be balanced over the economic cycle. This enables the budget to be used to moderate the business cycle via both its ‘automatic stabilisers’ and through discretionary changes to revenue and spending, while still avoiding excessive build up of government debt over the medium-term and longer. This anchor for fiscal policy has served Australia well for many years.

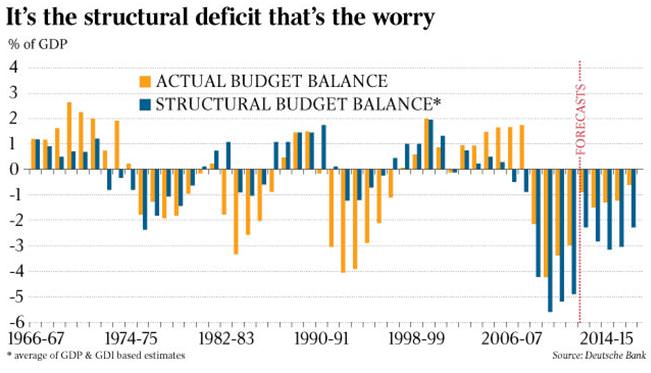

For this reason, the budget deficit or surplus has to be looked at in structural (or cyclically-adjusted) terms as well as in cash terms. Deutsche Bank ran the numbers prior to the release of the 2013 budget numbers, and concluded that “the structural deficit (ie abstracting from the impacts of higher commodity prices and the economic cycle) will be around 2¼% of GDP in 2012-13. Looking forward we estimate the structural deficit will still be around 2¼% come 2016-17 … we see the structural deficit averaging more than was seen under either the Whitlam or Fraser governments.”

Of course, most other western countries have structural budgets and levels of government debt on issue significantly higher than ours, although Canada and New Zealand are likely to return to surplus before we do. And the Coalition Government didn’t run surpluses as large as the prosperous times before the global financial crisis really dictated they should have. Norway’s larger surpluses, fed in that country’s sovereign wealth fund, suggest the route we should have followed.

The worry about persistent deficits

In the words of the Grattan Institute, persistent budget deficits “incur interest payments, and limit future borrowings … they can unfairly shift costs between generations, and reduce flexibility in a crisis”. In my view, the problems facing Europe, where the global financial crisis morphed into a sovereign debt crisis, demonstrate the pain that comes from persistent budget deficits (aggravated of course by the common currency). Deutsche Bank adds, “given the budget will be in deficit … the Federal Government is now contributing to the current account deficit”.

A balanced budget over the economic cycle is generally favourable for investors, because it improves prospects that real returns in assets will be more stable, predictable and attractive than they’d otherwise be. Similarly, a balanced budget over the economic cycle generally helps to restrain inflation which, when tolerated, creates pain and uncertainty for investors, particularly for self-funded retirees living from savings.

Deutsche Bank also reminds us that “to the extent that unaffordable policies drive dire projections of the budget position, such policies will not see the light of day in unaltered form” - and, I’d add, they can cause the government to cut deeply into current programmes, even popular and efficient ones. When governments live beyond their means, uncertainties build up and costs are imposed because the bills still have to be paid somehow.

Don Stammer is an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund, Altius Asset Management and Philo Capital. The views expressed are his alone.