In the Future Fund’s FY25 Annual Report, Chair Greg Combet highlighted that the fund will not be paying defined benefit pensions (DBPs) until at least 2033 - some 27 years after the fund was formed and 13 years later than its original design.

The Chair stated:

"The deferral of withdrawals ensures that the Future Fund can continue to strengthen the Australian Government's long-term financial position and make sustainable contributions to the Budget.

This was a welcome decision as it provides our organisation, certainty to continue to build the portfolio and structure the Agency for a longer-term future.

By 2032-33, the Future Fund is expected to grow to $380 billion. That should enable not only all of the pension liabilities to be met over ensuing decades but also generate earnings that form the basis of an enduring sovereign wealth fund."

Let me unpack this statement and draw some conclusions:

- Deferral of withdrawals is a quaint way of saying that the Future Fund (“the Fund”) will not pay pensions. The Australian taxpayer, through the budget, is paying at least $14 billion p.a. in DBPs. This annual amount will grow in each year and until the Fund takes responsibility for payments.

- In 2033, according to the Fund Chair, it is expected that the liability of DBPs will be $380 billion. The original estimate in 2006 was $140 billion - oops!

- If the expected liability is suggested to be $380 billion in 2033, then it is $380 billion today - that is the known liability - and not the $313 billion in budget papers - oops!

- If the Australian taxpayer will pay an estimated total of $120 billion in DBPs over the next 7 years, then the true liability is actually $500 billion - oops!

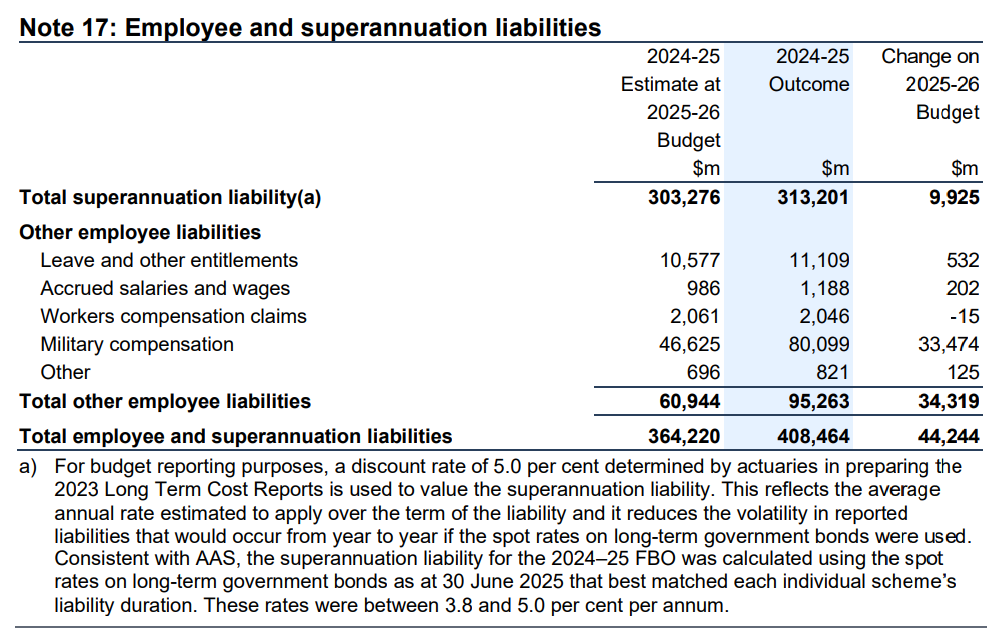

I refer readers to disclosures in the recent FY25 Australian Budget outcome statement. The following table from the budget papers shows the superannuation liability (i.e. defined benefits) of the Commonwealth as $313 billion, a $9.9 billion increase over that forecast on budget night, just six months ago, in March 2025! The movement of the liability is a work of art by the Commonwealth Actuary, and they have never been conservative in any of their estimates over the last 20 years.

The lack of transparency and the constant upward movement in the estimate of he defined benefit liability is breathtaking. The lack of critical questioning of these points by Senators in Committee or by the Opposition in Question Time, suggests the cover up is bipartisan, with beneficiaries of DBPs having considerable influence.

Further, it has now become standard practice for the budget papers to understate the net debt of the Commonwealth by excluding DB labilities. Again, I refer readers to the following snippet from the FY25 Budget outcome.

So where to for the Future Fund?

Simple observations and mathematics suggest that there is much hidden from the taxpayer concerning the true size of the DB liabilities, and the true amounts of the annual pension payments over the next 30 or so years.

For instance, if the Fund reaches $380 billion in 2032 and it then has cash earnings of 5% (investing as pension fund), then the $19 billion p.a. of income should ensure that the Fund’s capital will never run out. Of course, that assumes that the Fund Chair has accurately forecast the liability, based on correct forecasts from the Department of Finance and the Commonwealth Actuary.

I wonder how confident these public servants are with their forecast because the current earnings of the Fund appear greater than the current annual pension payments being made by taxpayers. Thus, if the Fund had paid its pension liabilities in FY25, then the Commonwealth would have turned a $10 billion deficit into a fiscal surplus. So why didn’t it?

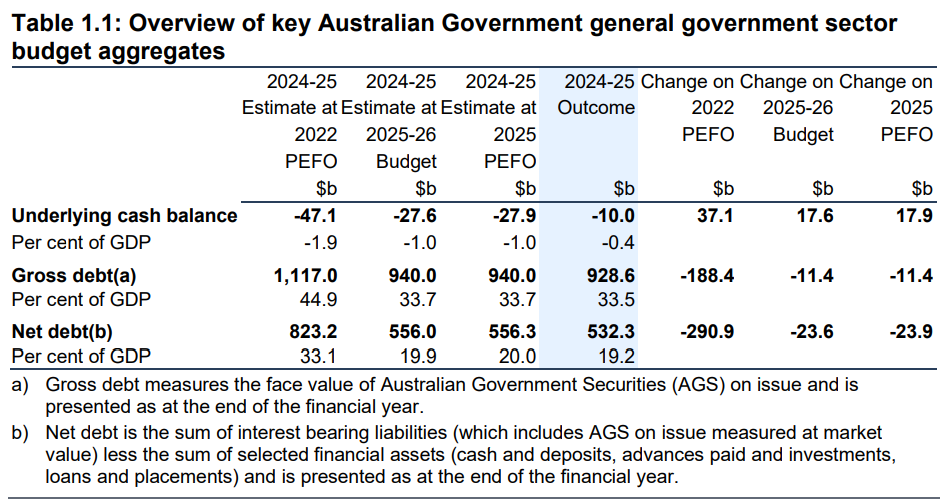

The next table highlights the extraordinary misforecast in March of the June year ended budget outcome. Treasury got it wrong by $17.8 billion or about $4 billion per month! Therefore, can taxpayers believe any forecast in the budget papers?

The Future Fund may be needed to solve a financial calamity

Here is a prediction that flows from Australia's immense and growing housing price bubble.

By 2030 it may become a social imperative to deal with the significant cohort of indebted households who have a mortgage that has either negative equity, or which cannot be paid back during the working lives of the borrower. Any house price correction will create an urgent need for a solution as it will risk a financial system calamity for our banks. Provisioning for negative equity could eat up profits and pull-down bank capital.

The Fund sits with a bundle of capital and a growing pension liability that will surely need a predictable and secure income source from Australian assets by 2033. Mortgage capital and interest fit the bill. Further, the banks may be asked to top up the yield to the Fund if they are averting provisioning by transferring vulnerable mortgage assets.

Based on current growth rates the size of Australian mortgage debt will exceed $3.5 trillion in 2030. If 10% of that debt is classified as in stress, then it may be appropriate to transfer those loans from the banks to the Fund (the Commonwealth).

Therefore, the Fund could be turned in to a "bad mortgage" fund, allowing the banks to relieve themselves of problem loans, in conjunction with the reintroduction of qualitative controls, needed to regulate credit for housing. That is, a proper reset to minimum deposit ratios. The benefit will be that the Fund will acquire assets whose cashflow will meet its pension payout needs.

Importantly, proper regulation of the provision of debt will mean that “5% deposit schemes” proposed by the government for "first home buyers" will not be necessary because residences will become more affordable under a housing policy that acts to limit leveraged demand.

The likely pain, represented by housing price declines, will be shared with the Fund that has abundant taxpayer capital. Indeed, the most vulnerable borrowers will be protected from lenders who will surely panic when the inevitable housing correction occurs.

John Abernethy is Founder and Chairman of Clime Investment Management Limited, a sponsor of Firstlinks. The information contained in this article is of a general nature only. The author has not taken into account the goals, objectives, or personal circumstances of any person (and is current as at the date of publishing).

For more articles and papers from Clime, click here.