The retail property landscape has faced a number of challenges over the past five years, from e-commerce to pandemic lockdowns, squeezed household wallets, and weak consumer sentiment. But one centre type has stood tall through it all – Neighbourhoods. These convenience-oriented centres are the cornerstones of local communities and offer a compelling investment proposition underpinned by several advantageous characteristics.

Income security

Neighbourhood shopping centres are supermarket-based and heavily weighted to blue chip tenants such as Woolworths, Coles and Aldi. These brands are strong, providing exceptional credit quality and security of income. Their leases are also long, typically 20 years with multiple options to extend, further reducing the variability of income received.

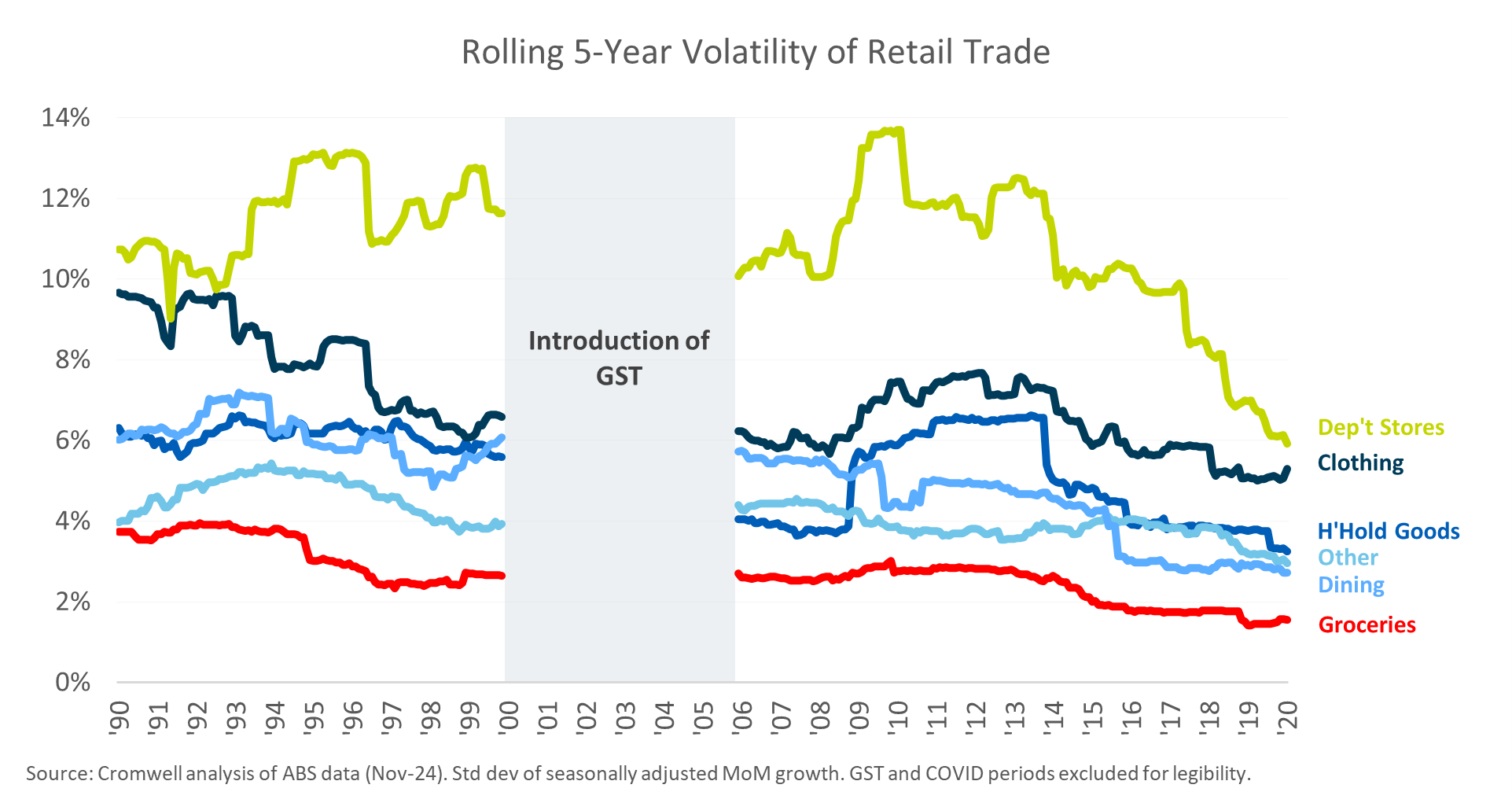

Demand stability

A selection of specialty tenants complements the grocery offer. These smaller shops often span essential categories such as food, services and healthcare, rather than non-essential items such as fashion. This tenant mix means Neighbourhoods are largely focused on meeting basic, long-term human needs rather than fleeting style or brand preferences. As a result, these assets benefit from steady demand and foot traffic, regardless of the business cycle or economic conditions, evident in the lower volatility of grocery sales.

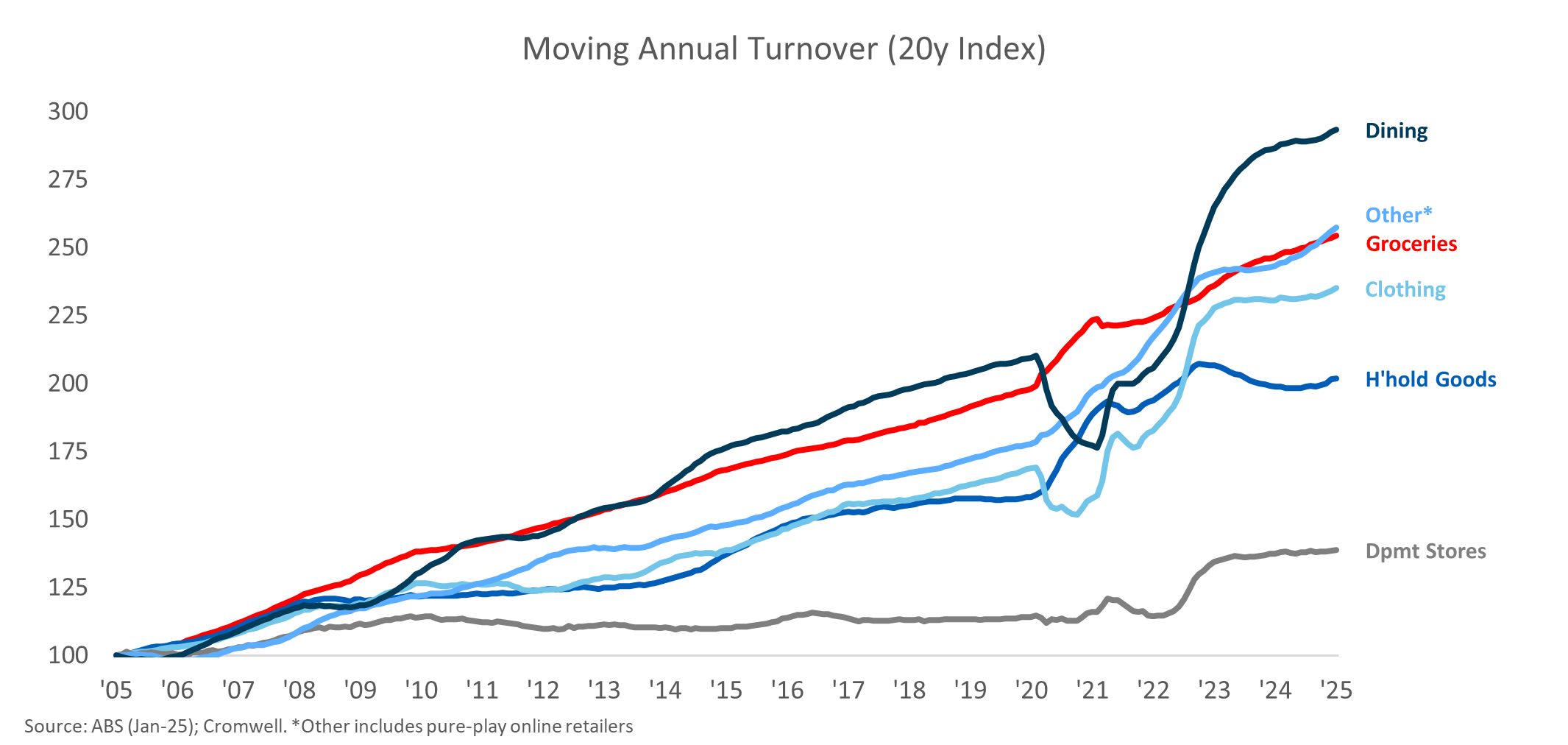

Growth tailwinds

Positively, the lower volatility of grocery spending doesn’t come at the expense of growth. The category has recorded growth of 4.9% p.a. over the last 20 years, behind only Dining and Other (which includes online-only retailers) [1]. One of the factors underpinning headline grocery trading performance is inflation. Since groceries are essential and demand is inelastic, price increases can be more readily passed on to consumers compared to non-essential items. Deflationary effects from technology advancement or cheaper offshore sourcing also apply to a lesser extent than in the case of categories such as electronics or clothing. Stronger headline sales growth supports sustainable rent increases, which escalate on a nominal basis.

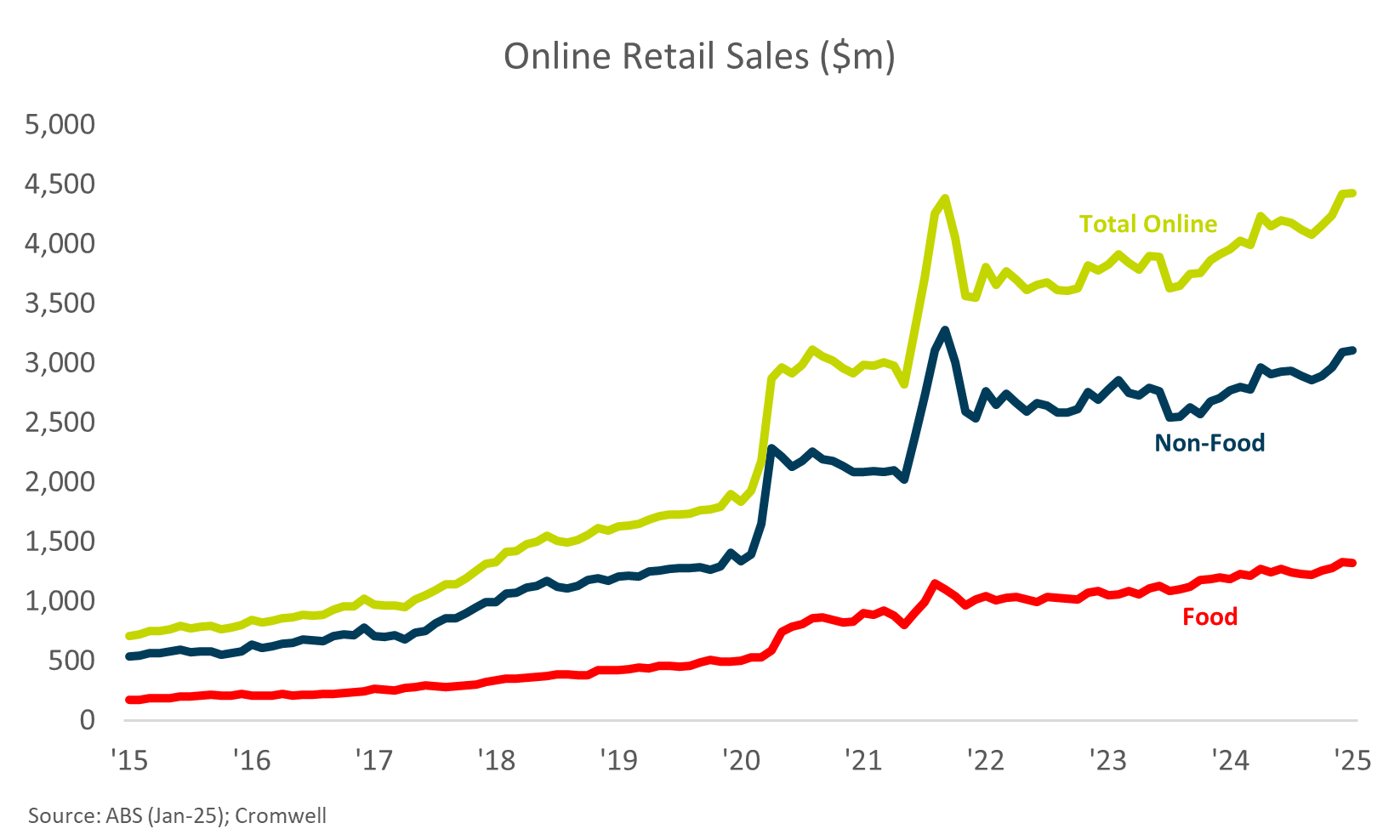

E-commerce resilience

Growth through physical stores, rather than online, is most relevant for the performance of shopping centres. Over the last ten years, for every extra dollar spent on food (like groceries and dining), 16 cents went to online purchases. Meanwhile, non-food items lost 43 cents to online sales [1]. In this regard, Neighbourhood centres have a favourable retail mix which is heavily weighted to food spending through supermarket and specialty grocery exposure. They also have a healthy weighting to categories which consumers must shop in-person, such as personal services (e.g. hairdressing). We also believe the shopping experience small local centres provide, underpinned by convenient carparking and wayfinding, further defends against loss of market share to e-commerce.

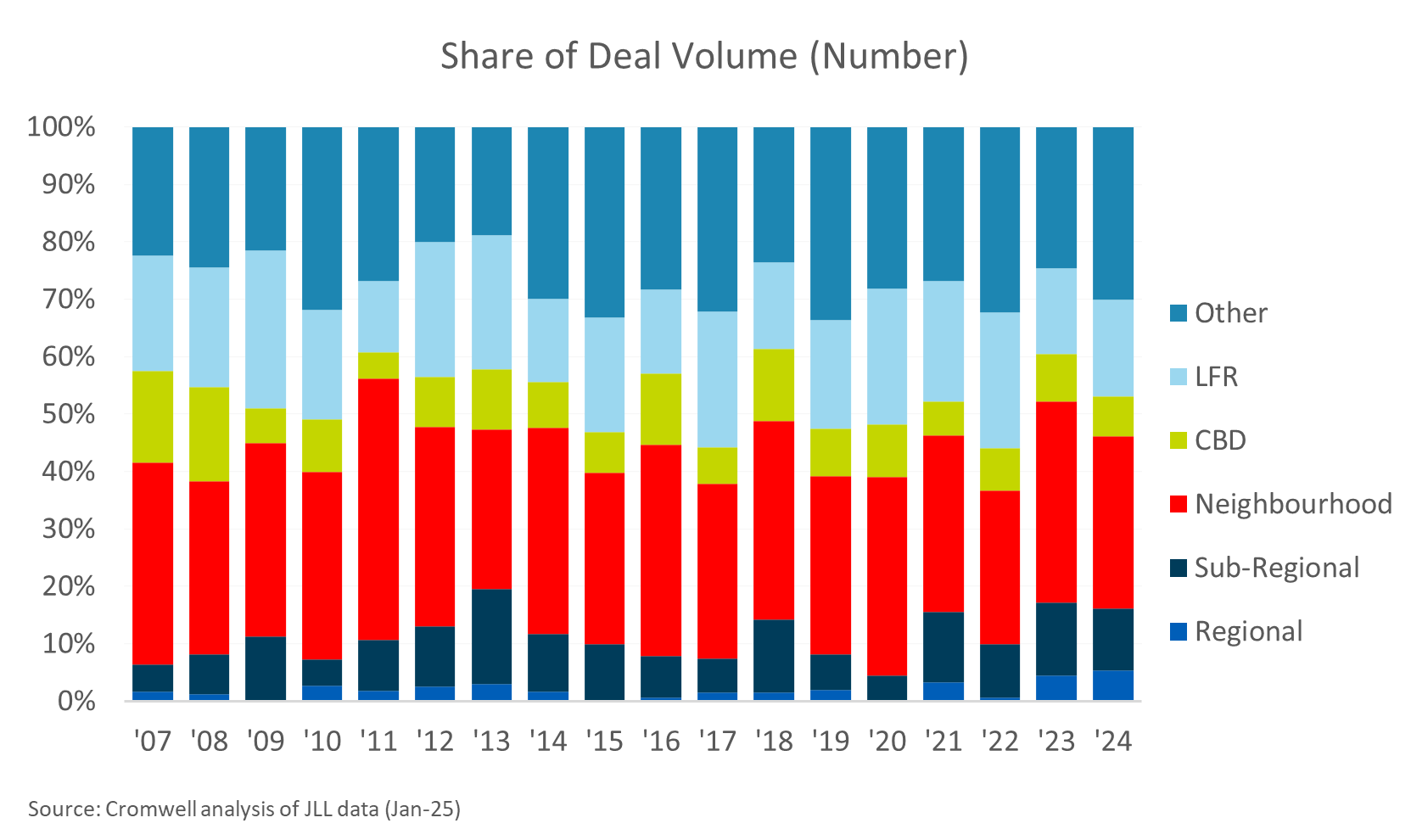

Bigger investment universe

Larger forms of retail investment, such as Regional shopping centres, can only be sustained in catchments with sizable populations (i.e. major metropolitan hubs). In contrast, Neighbourhood centres are found in cities and towns all across the country. This provides investors with a less constrained and more diverse investment universe which is around 30 times bigger (by number of assets). It allows exposure to a wider range of regions/catchments and their associated drivers of economic performance.

Investment liquidity

The Neighbourhood investment market is broader than other retail centre types, offering increased liquidity and supporting a competitive bidding process (and outcome) regardless of position within the economic or real estate cycle. Over the last decade, an average of 51 Neighbourhood centres transacted each year compared to 15 Sub-Regionals and four Regionals. Trading was most constrained in 2020, at the height of the pandemic. In that year, there was still 38 Neighbourhoods sold, while only five Sub-Regionals and no Regionals changed hands.

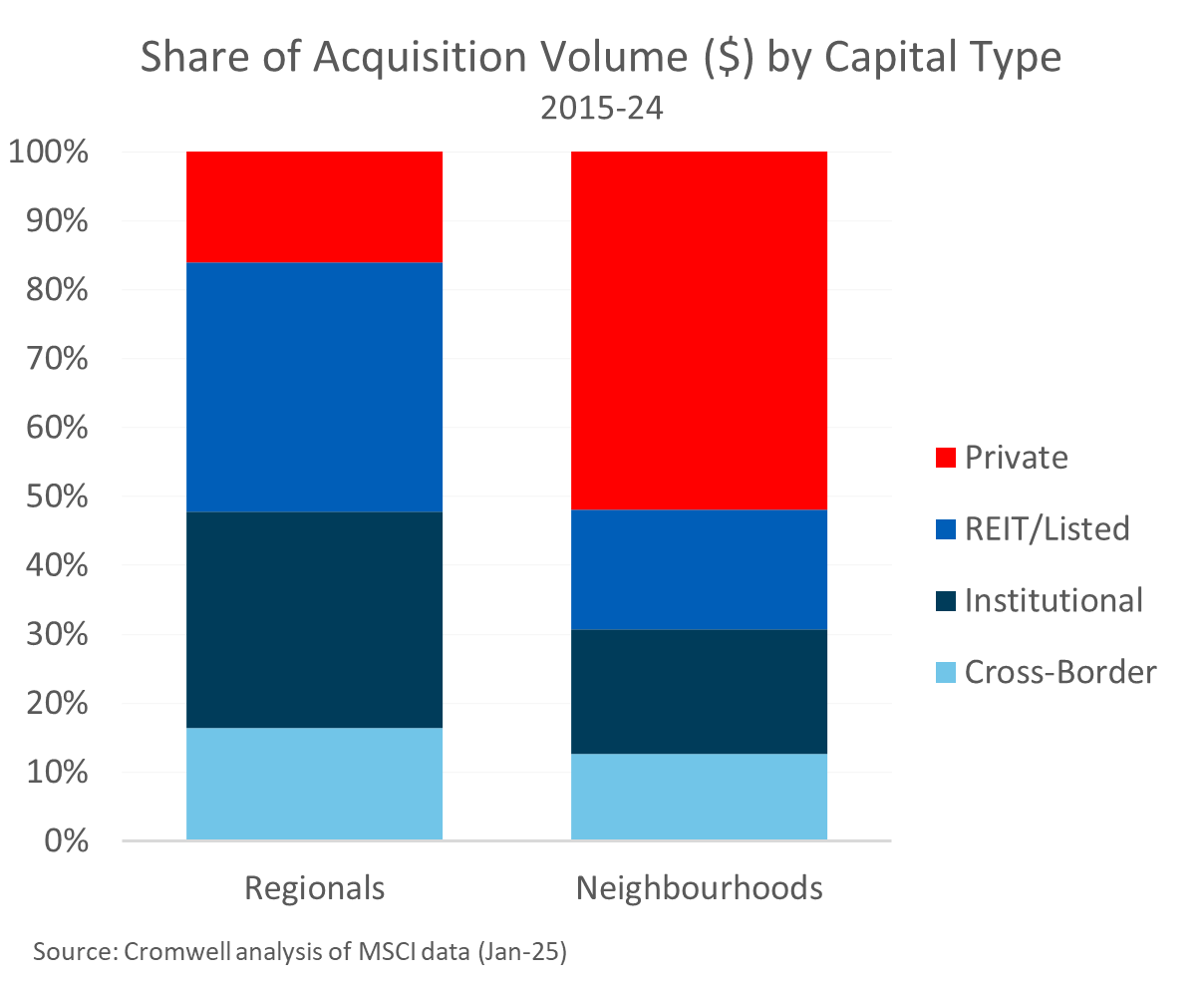

Fragmented sector

Ownership of Neighbourhoods is more fragmented than other retail centre types. While Regional shopping centres are typically owned by a small number of institutional investors, private investors are the dominant holders of Neighbourhoods. These private investors have different skills, goals, and priorities, which can affect how well the centres are maintained and managed. In our opinion, this presents opportunities for experienced managers to “add value” to assets through capital projects, leasing and operations, and increases the likelihood that an asset can be acquired and sold at favourable pricing.

Bringing home the bacon

Retail conditions are expected to improve over 2025, with consumer sentiment becoming more optimistic and real disposable household incomes increasing as inflation moderates and rate cuts materialise. Stronger retail conditions are a positive for Neighbourhoods, but these shopping centres will also benefit from their unique characteristics and advantages. The combination of strong, long-term leases to blue-chip tenants, consistent bricks and mortar demand for essential goods and services, and resilience to changing economic and capital market conditions has positioned Neighbourhood centres as a robust and attractive asset class.

[1] Cromwell analysis of ABS data (Jan-25)

Colin Mackay is a Research and Investment Strategy Manager for Cromwell Property Group. Cromwell Funds Management is a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is not intended to provide investment or financial advice or to act as any sort of offer or disclosure document. It has been prepared without taking into account any investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Any potential investor should make their own independent enquiries, and talk to their professional advisers, before making investment decisions.

For more articles and papers from Cromwell, please click here.