“More than any other time in history, mankind faces a crossroads. One path leads to despair and utter hopelessness. The other to total extinction. Let us pray we have the wisdom to choose.” – Woody Allen

The ‘news’ as presented to us has always had a negative bent, but one could be forgiven for thinking that it’s become even more negative with constant stories of disasters, conflict, wrongdoing, grievance and loss. This was an issue prior to coronavirus – with trade wars, social polarisation, tensions with China, worries about job loss from automation and ever-present predictions of a new financial crisis. Since the pandemic higher public debt, inflation, geopolitical tensions and rising alarm about climate change have added to the worries.

These risks can’t be ignored yet when it comes to investing, the historical track record shows that succumbing to pessimism doesn’t pay.

Three reasons why worries might seem more worrying

Some might argue that since the GFC the world has become a more negative place and so gloominess or pessimism is justifiable. But given the events of the last century – ranging from far more deadly pandemics, the Great Depression, several major wars and revolutions, numerous recessions with high unemployment and financial panics – it’s doubtful that this is really the case viewed in the long-term sweep of history.

There is no denying there are things to worry about at present – notably inflation, political polarisation, less rational policy making and geopolitical tensions - and that these may result in more constrained investment returns. But there is a psychological aspect to this combined with greater access to information and the rise of social media to magnify perceptions around worries. All of which may be adding to a sense of pessimism.

Firstly, our brains are wired in a way that makes us natural receptors of bad news. Humans tend to suffer from a behavioural trait known as ‘loss aversion’ in that a loss in financial wealth is felt much more negatively than the positive impact of the same sized gain. This probably reflects the evolution of the human brain in the Pleistocene age when the key was to avoid being eaten by a sabre-toothed tiger or squashed by a wholly mammoth. This left the human brain hard wired to be on guard against threats and naturally risk averse. So, we are more predisposed to bad news stories as opposed to good. Consequently, bad news and doom and gloom find a more ready market than good news or balanced commentary as it appeals to our instinct to look for risks. Hence the old saying “bad news and pessimism sells”.

This is particularly true as bad news shows up as more dramatic whereas good news tends to be incremental. Reports of a plane (or a share market) crash will be far more newsworthy (generating more clicks) than reports of less plane crashes this decade (or a gradual rise in the share market) ever will. As a result, prognosticators of gloom are more likely to be revered as deep thinkers than optimists.

Secondly, we are now exposed to more information on everything, including our investments. We can now check facts, analyse things, sound informed easier than ever. But for the most part we have no way of weighing such information and no time to do so. So, it’s often noise. As Frank Zappa noted “Information is not knowledge, knowledge is not wisdom.”

This comes with a cost for investors. If we don't have a process to filter it and focus on what matters, we can suffer from information overload. This can be bad for investors as when faced with more (and often bad) news we can freeze up and make the wrong decisions with our investments. Our natural ‘loss aversion’ can combine with what is called the ‘recency bias’ – that sees people give more weight to recent events in assessing the future – to see investors project recent bad news into the future and so sell after a fall.

Thirdly, there has been an explosion in media competing for attention. We are now bombarded with economic and financial news and opinions with 24/7 coverage by multiple web sites, subscription services, finance updates, dedicated TV and online channels, chat rooms and social media. This has been magnified as everything is now measured with clicks - stories (and reporters) that generate less clicks don’t get a good look in. To get our attention news needs to be entertaining and following from our aversion to loss, in competing for our attention, dramatic bad news trumps incremental good news and balanced commentary. So naturally it seems the bad news is ‘badder’ and the worries more worrying than ever which adds to a sense of gloom. The political environment has added to this with politicians more polarised and more willing to scare voters.

Google the words “the coming financial crisis” and it’s teeming with references – 270 million search results at present – and as you might expect many of the titles are alarming:

- “A recession worse than 2008? How to survive and thrive.”

- “Could working from home cause the next financial crisis?”

- “Economic crash is inevitable.”

- “Three men predicted the last financial crisis – what they’re warning of now is terrifying.”

- “How China’s debt problem could trigger a financial crisis.”

The danger is that the combination of the ramp up in information and opinion, combined with our natural inclination to zoom in on negative news, is making us worse investors: more distracted, pessimistic, jittery and focused on the short-term.

Three reasons to be optimistic as an investor

There are three good reasons to err on the side of optimism as an investor.

Firstly, without a degree of optimism there is not much point in investing. If you don’t believe the bank will look after your deposits, that most borrowers will pay back their debts, that most companies will see rising profits over time supporting a return to investors, that properties will earn rents, etc, then there is no point investing. To be a successful investor you need to have a reasonably favourable view about the future.

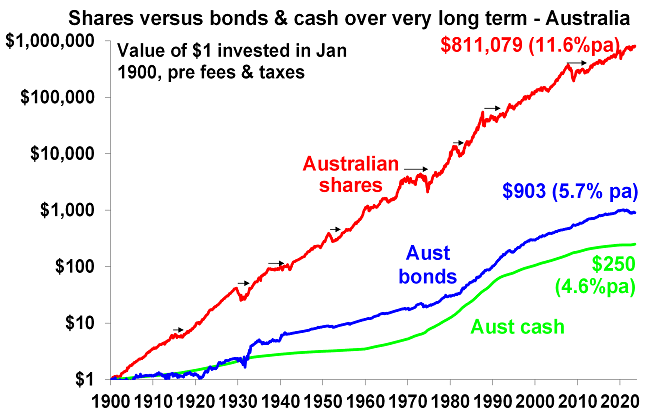

Secondly, the history of share markets (and other growth assets like property) in developed well managed countries with a firm commitment to the rule of law has been one of the triumph of optimists. Sure, share markets go through bear markets and often lengthy periods of weakness – where pessimists get their time in the sun - but the long-term trend has been up, underpinned by the desire of humans to find better ways of doing things resulting in a real growth in living standards. This is indicated in the next chart which tracks the value of $1 invested in Australian shares, bonds and cash since 1900 with dividends and interest reinvested along the way. Cash is safe and so fine if you are pessimistic but has low returns and that $1 will have only grown to $250 today. Bonds are better and that $1 will have grown to $903. Shares are volatile (and so have rough periods – see the arrows) but if you can look through that they will grow your wealth and that $1 will have grown to $811,079.

Source: ASX, Bloomberg, RBA, AMP

This does not mean blind optimism where you get sucked in with the crowd when it becomes euphoric or into every new whiz bang investment obsession that comes along (like bitcoin or the dot com stocks of the 1990s). If an investment looks too good to be true and the crowd is piling in, then it probably is - particularly if the main reason you are buying in is because of huge recent gains. So, the key is cautious, not blind, optimism.

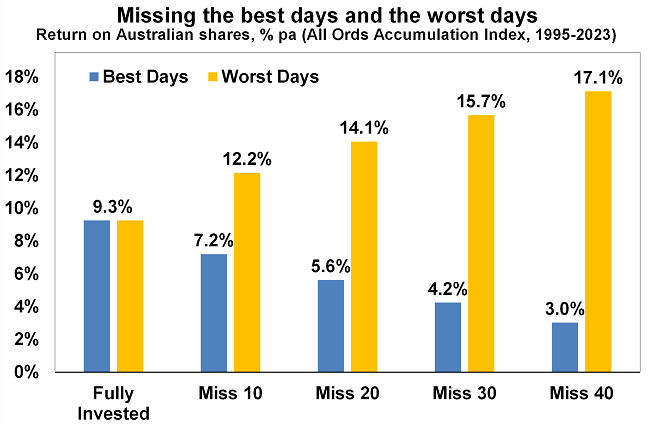

Finally, even when it might pay to be pessimistic and hence out of the market in corrections and bear markets, trying to get the timing right can be very hard. In hindsight many downswings in markets like the GFC look inevitable and hence forecastable and so it’s natural to think you can anticipate downswings going forward. But trying to time the market – in terms of both getting out ahead of the fall and back in for the recovery - is difficult. A good way to demonstrate this is with a comparison of returns if an investor is fully invested in shares versus missing out on the best (or worst) days. The next chart shows that if you were fully invested in Australian shares from January 1995, you would have returned 9.3%pa (with dividends but not allowing for franking credits, tax and fees).

Covers Jan 1995 to March 2023. Source: Bloomberg, AMP

If you were pessimistic about the outlook and managed to avoid the 10 worst days (yellow bars), you would have boosted your return to 12.2%pa. And if you avoided the 40 worst days, it would have been boosted to 17.1%pa! But this is very hard, and many investors only get really pessimistic and get out after the bad returns have occurred, just in time to miss some of the best days. For example, if by trying to time the market you miss the 10 best days (blue bars), the return falls to 7.2%pa. If you miss the 40 best days, it drops to just 3%pa.

As famed investor Peter Lynch has pointed out “More money has been lost trying to anticipate and protect from corrections than actually in them.”

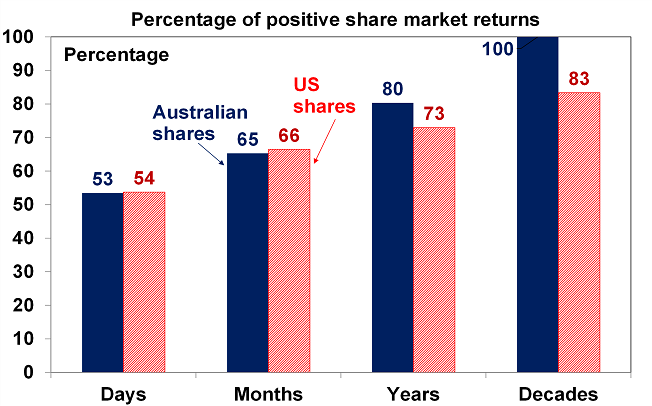

On a day-to-day basis it’s around 50/50 as to whether shares will be up or down, but since 1900 shares in the US have had positive returns around seven years out of ten and in Australia it’s around eight years out of ten.

Daily & mthly data from 1995, data for years & decades from 1900. Source: ASX, Bloomberg, AMP

So getting too hung up in pessimism on the next crisis that will, on the basis of history, drive the market down in two or three years out of ten may mean that you end up missing out on the seven or eight years out of ten when the share market rises. Here’s one final quote to end on:

“No pessimist ever discovered the secrets of the stars, or sailed to an uncharted land, or opened a new heaven to the human spirit.” – Helen Keller

Dr Shane Oliver is Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist at AMP and AMP Capital. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs.