When we talk about Australia’s housing crisis, the focus tends to fall on two things: supply versus demand. This article looks at one aspect of supply which is often (well frankly almost always) overlooked – spare bedrooms.

Now the headlines cry “Build more homes,” and yes - in many cases, that’s the right answer.

But what if – just what if – we already had a massive, underutilised stockpile of housing hiding in plain sight? Not in paddocks, not in construction pipelines, but behind closed doors. But in homes already built.

Bedrooms already plumbed, insulated, and sitting idle.

The latest estimates suggest Australia has over 13 million spare bedrooms – across both occupied and unoccupied dwellings. It’s the biggest untapped housing asset in the country - and it’s been quietly ignored for decades.

Let’s take a closer look.

The scale of the surplus

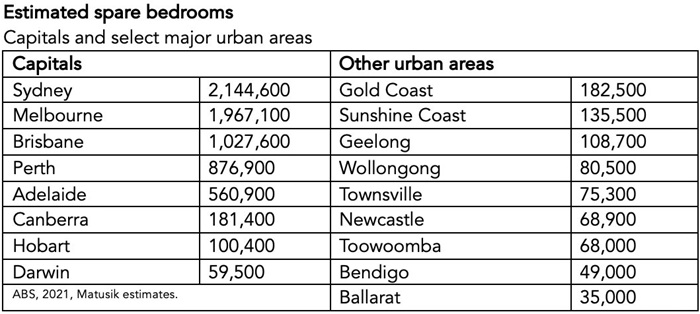

Let’s start with the numbers. From the 2021 Census:

- There were 10.85 million private dwellings across Australia

- Of these, 1.04 million were completely unoccupied on Census night

- The remaining 9.81 million were occupied - and more than 75% of those had at least one spare bedroom

Using a conservative benchmark – that households only ‘need’ one bedroom for every two people (rounded up) – we estimate that between 9.8 and 11 million bedrooms in occupied homes are surplus to need.

Now let’s add in the unoccupied homes. Here we have assumed that the unoccupied stock on average holds two bedrooms on average. Why? Because most unoccupied dwellings are apartments, holiday lets, or modest second dwellings – not suburban homes or even townhouses.

So: 1.04 million unoccupied dwellings × 2 bedrooms = 2.08 million spare bedrooms

That brings our revised national total to between 11.9 to 13.1 million ‘spare’ bedrooms across Australia.

That’s one empty bedroom for every two people in the country.

We don’t have a housing shortage. We have a housing misallocation problem and one that’s literally hiding behind closed doors.

How does this happen?

The short version is that we’ve built our housing around a vision of the nuclear family that no longer reflects how we live.

- Older Australians are staying put in large homes long after their children have moved out.

- Young people are priced out of renting anything beyond a share house, let alone buying.

- Solo living is rising, but zoning and planning rules still prefer traditional housing solutions.

- Empty nesters with 3 or 4 bedrooms often want to downsize – but can’t find or afford anything nearby to move into.

And so, we end up with one part of the population rattling around in too much space - while others (too many) can’t find a place to sleep.

Why aren’t spare bedrooms being used?

It’s not as simple as blaming homeowners. There are real barriers to putting those rooms to work:

- Tax disincentives – Rent out a room, and you might affect your pension, trigger CGT, or face complex ATO reporting.

- Legal uncertainty – Residential tenancy laws are geared toward full leases, not shared arrangements.

- Safety/privacy concerns – Homeowners are wary about inviting strangers into their personal space.

- Insurance and liability issues – Many home insurers don’t cover shared arrangements without premium hikes.

- No trusted platforms – There’s no national, vetted service to match up homeowners and renters safely.

So even where the will exists, the system says: “Too hard”.

What’s been tried — And what’s worked?

Let’s look at some real-world examples, here and abroad:

- Bathurst, Orange & Parkes (NSW)

A 2022 pilot project mapped ‘spare room capacity’ in these regional centres. It found over 60,000 spare bedrooms - enough to house an entire workforce. But uptake was blocked by concerns about trust, risk, and the lack of enabling regulation.

- Homeshare Programs (UK, Germany, Australia)

Homeshare initiatives pair older people with a spare room with younger people needing affordable accommodation. In exchange for cheap rent, the renter helps with tasks like shopping or gardening. These schemes have run successfully in the UK, Germany, and parts of Australia (e.g. Anglicare trials in Queensland), improving wellbeing and extending ageing-in-place.

- The UK’s Bedroom Tax (2013)

In a more hardline move, the UK cut housing benefit for social housing tenants with spare rooms. While it did free up some properties, it also pushed vulnerable people into hardship – particularly where smaller homes weren’t available. Lesson: penalties without options don’t work.

- Victoria’s Short-Stay Levy (2024)

By slapping a 7.5% levy on Airbnb-style short-stay rentals, Victoria is hoping to shift some properties back to long-term use. It won’t affect spare bedrooms directly, but it sends a signal: housing is for living in, not just profiting from.

Five things Australia could do and now

Unlocking just 5% of the country’s underused bedrooms would yield over 650,000 new sleeping spaces. That’s more than all the new homes Australia is forecast (dreaming) to build in the next two years!

Here’s how we do it:

- Tax incentives for micro-letting

Offer tax-free thresholds for renting a room – say, up to $10,000/year – and remove CGT triggers for part-use of the home.

- Create a ‘micro-tenancy’ legal category

We need a simple, low-risk legal structure – partway between a tenancy and a licence – to allow flexible, low-commitment rental agreements.

- Subsidise retrofit upgrades

Grants or low-interest loans to install locks, private entries, or minor conversions could turn awkward spare rooms into viable living quarters.

- Nationally backed matching platforms

Think ‘Airtasker meets Airbnb meets Homeshare’ – with government-vetted profiles, insurance coverage, and dispute mediation.

- Permit internal subdivisions without full rezoning

Allow larger homes to be split into dual-occupancy dwellings (internally), provided safety, fire, and access requirements are met – but without full subdivision or title separation.

The bigger picture

I am not saying stop building new homes – far from it. But I am saying: don’t ignore the elephant in the spare room.

Housing is a system – and right now, it’s running with gross inefficiencies. The mismatch between household sizes and dwelling sizes is one of the biggest – and easiest to fix – distortions in the market.

Every spare bedroom we unlock is a bed for someone instead of sleeping on a couch, in their car, or in a motel paid for by the state. This isn’t just a housing issue – it’s a productivity issue, a wellbeing issue, and a moral one.

End note

Australia doesn’t just have a housing shortage. It has a housing distribution problem.

Our cities are full of three- and four-bedroom homes with one or two people inside. And our tax settings reward sitting on assets – not sharing them.

And my suggested solutions aren’t radical. They’re simple, human, and working elsewhere but we need to be creative and do something.

The housing crisis isn’t just about what we haven’t built. It’s also about what we’ve built and aren’t using.

Michael Matusik is an Australian housing market specialist, providing commissioned housing and demographic market reviews, updates and outlooks for over 30 years, and shares his thoughts in his blog, Matusik Missive.