The RBA has increased interest rates to tame inflation and there’s no shortage of knee jerk reactions. About how it hurts homeowners (of course); about what the RBA will do next, even though almost no one forecast the rate rise a mere four months ago; and about how the government is or isn’t to blame, depending on which side of politics you support.

A lot of the discussion seems short-sighted and fails to answer several key questions:

What are the real drivers behind our high inflation?

Why do many people feel worse off than the official consumer price index figures suggest?

How can we fix the affordability crisis?

What are the risks that this becomes a long-term issue rather than just a temporary one?

Here I’ll attempt to answer those questions, so let’s get to it.

We live in a structurally higher inflation world

I’m not sure about you but I look at the prices of lollies today and naturally compare them to the prices that I paid as a kid. It’s hard to get my head around a lolly which cost me 20 cents as a child being priced at $2 now.

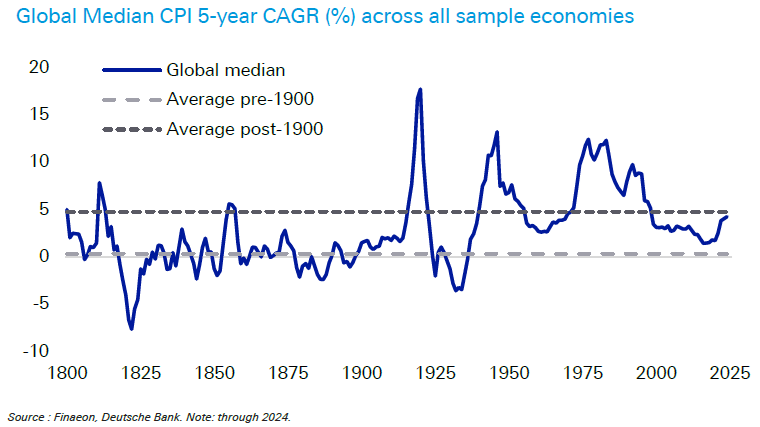

What most people don’t realise is that the price hikes that they see on a day-to-day basis are part of a broader, global trend. Over the past century, and especially since the 1970s, we’ve lived in a structurally higher inflation world.

That’s due to the world economy gradually loosening its ties to gold-based money, driven by shocks including the Great Depression, two World Wars, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods agreement.

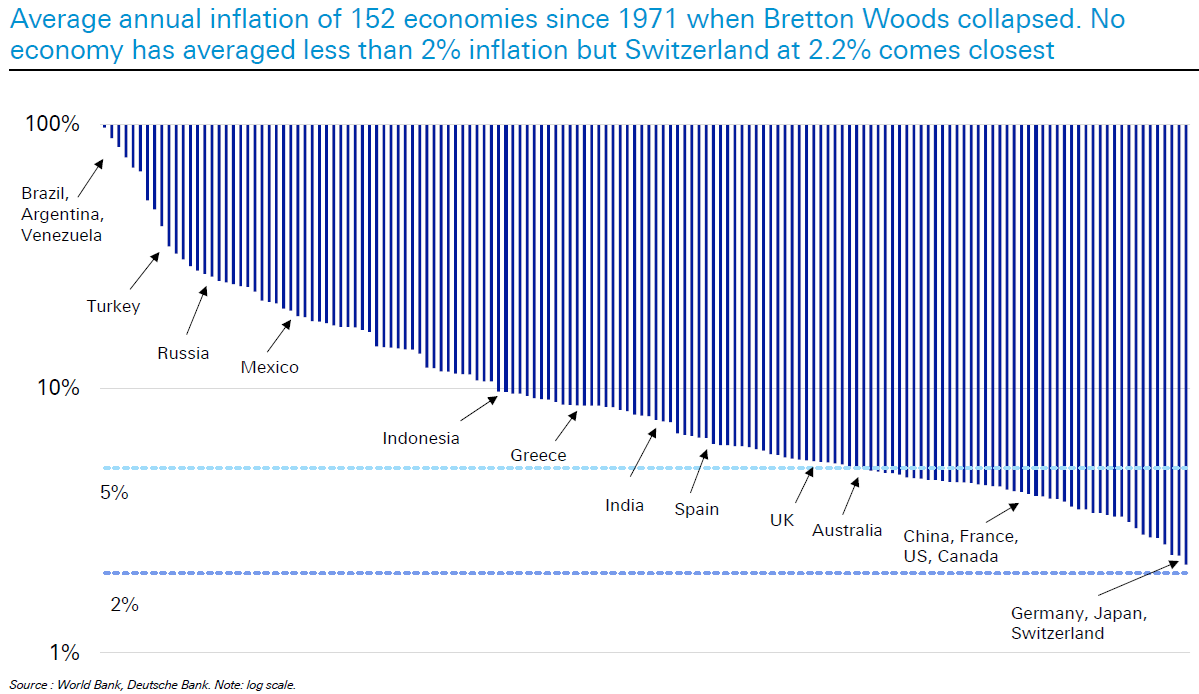

It may surprise people that since the world went off the gold standard in 1971, inflation in Australia has averaged 5%. That’s a big number – it means prices since then have doubled every 14 years or so. Which gives context to why my lolly prices have increased so much since my childhood.

The other thing that may surprise is that no country has managed to keep annual inflation below 2% since 1971. And only a handful of countries have kept annual inflation below 3% during that period.

This gives you context for the RBA’s targeted inflation band of 2-3% and how achievable that may or may not be in the long-term.

So, while the media in Australia focus on inflation here, it really is a global issue.

That’s not to diminish the fact that we do have higher inflation than many other developed countries right now and that there are idiosyncratic factors behind this.

Let’s talk about housing

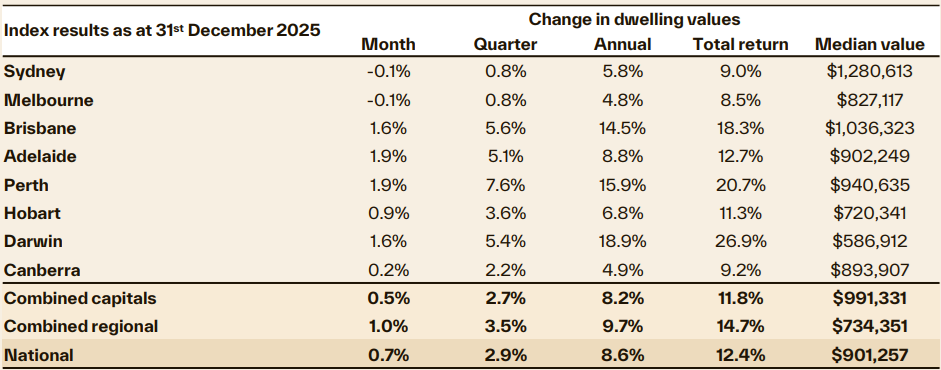

One key driver behind Australia’s affordability problems is the high cost of housing. On some metrics, we have the world’s most expensive homes.

Unbeknownst to most people, housing is largely excluded from official inflation figures. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is considered a de-facto cost of living index and, though it includes rents, it excludes the cost of land and mortgage interest payments. Given that land accounts for 75% of housing values, it means a large chunk of house price rises aren’t captured in the CPI.

Since 2000, the CPI has increased by 94%, but the median house price in capital cities has risen almost five-fold, from $200,000 to close to $1 million.

Even during 2025, the CPI increased 3.8%, while housing prices rose 12% in capital cities.

Source: Cotality

The CPI effectively ignores price changes in the single biggest purchase people are likely to make – a home. For the 37% of households that don’t own a home though wish to, the CPI is an inadequate measure of changes in the cost of living. And most of that 37% are our younger people.

It’s one of the reasons why many people feel costs are rising faster than the official inflation figures – because for them, they are.

That’s not to say that housing should be included in the CPI – there are good reasons why it isn’t. It’s just to acknowledge that the index doesn’t fully capture the cost of living for a big part of the population.

Why isn’t the “i” word mentioned?

Government spending has copped the blame for the recent inflation spike, especially from a certain financial newspaper. There’s some justification for that as public spending blowouts have helped to push up demand for goods and services and crowded out more efficient private spending.

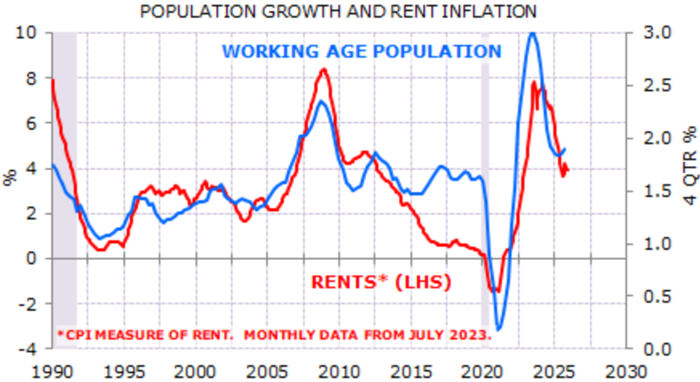

What hasn’t been mentioned nearly enough, though, is the influence of immigration on higher inflation.

As economist Gerard Minack rightly points out, housing construction and rents are the two largest items in the CPI and they contributed to the rise in inflation in the second half of last year. And both are driven in part by population growth.

Source: Gerard Minack

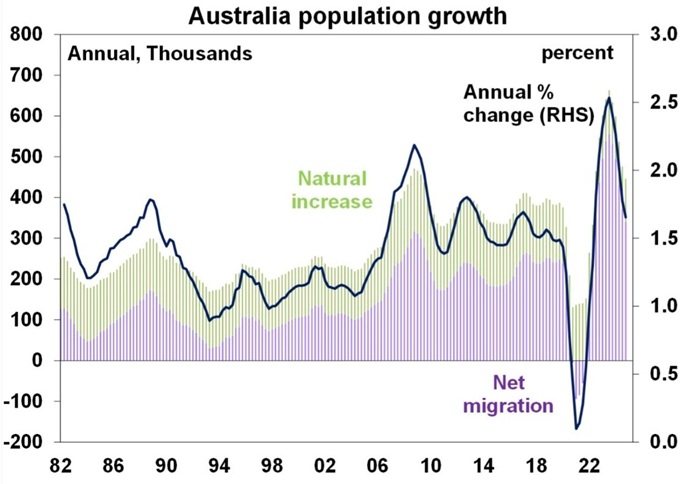

From 1945 to 2005, Australia averaged net migration around 90,000 annually.

Since then, both major political parties have advocated a ‘Big Australia’ policy that’s seen an unprecedented surge in our population.

The current Labor government has accelerated the migrant push, with net migration averaging 424,000 during its time in office.

There needs to be a mature discussion about the role that immigration has played in our cost of living crisis.

Yes, government spending isn’t helping

As mentioned, there’s little doubt that excessive government spending is playing some role in fuelling higher inflation. Government spending is now about 28% of GDP versus 21% a year ago.

Last financial year, federal government spending increased 8% after rising 9% the year before.

The problem for the current Labor government is that much of the spending appears structural rather than discretionary in nature.

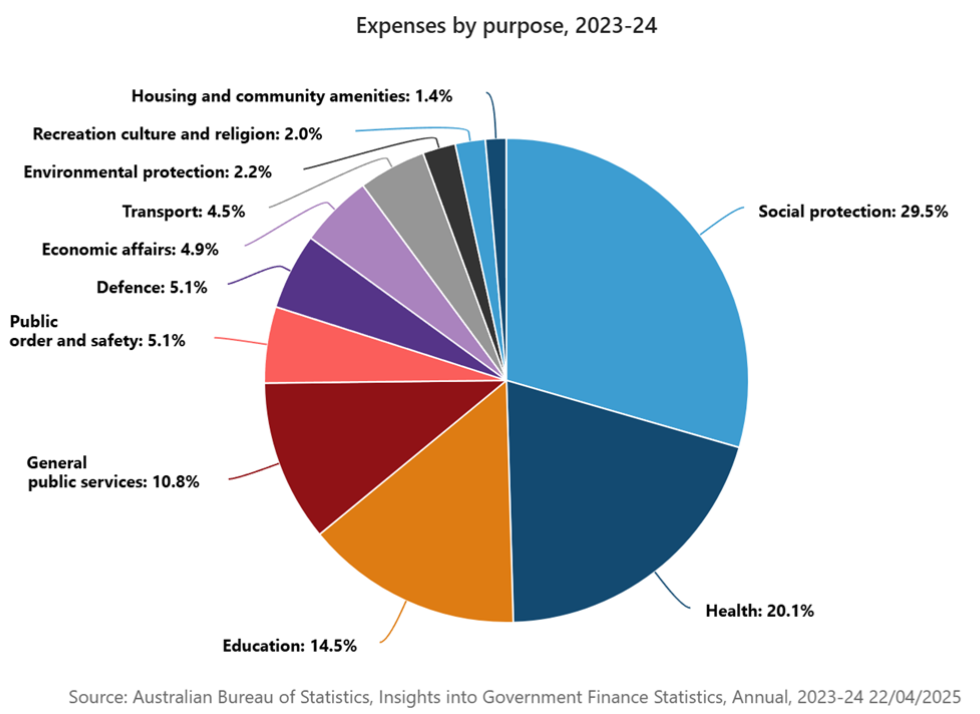

Of the $758 billion in federal government spending, about 30% goes towards welfare, 20% to health, 15% to education, and 5% to defence.

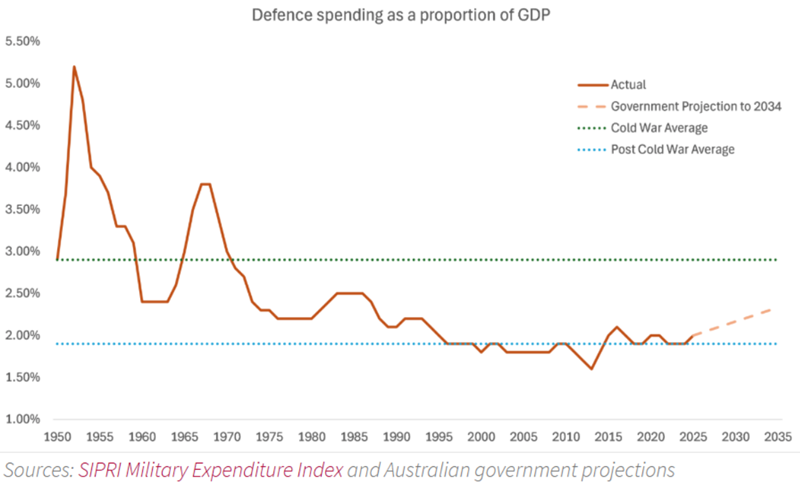

As Ben Walsh outlined in Firstlinks last week, defence spending will inevitably jump. Under pressure from the US to shoulder more of the defence burden, defence spending is projected to grow from $44.6 billion in 2026 to $56.2 billion by 2030 - a compound annual growth rate of 5.9%. As a percentage of GDP, this rises from 2.05% currently to 2.34% by 2032-33 under current government plans, with the opposition Coalition committed to reaching 3% of GDP within a decade. The US is pushing allies toward 3.5% of GDP.

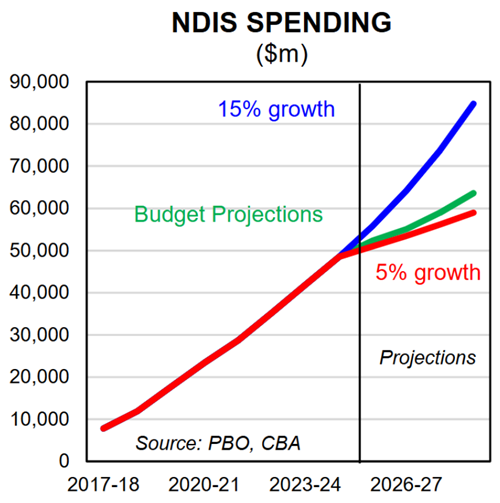

The biggest issue for the government is growth in the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). It’s gone from essentially nothing a decade ago to a $46 billion program now – about 6% of total government spending. And with forecast growth of close to 8% going forwards, that spending is on track to potentially double over the next 10 years.

Everybody, bar the government, seems to know that NDIS spending is out of control.

Over the Christmas break, I was speaking with a friend who is a chiropractor. He described how allied health businesses had restructured their practices to milk the most money from the NDIS program. He said some allied health services received little in NDIS funds, while others received quite a lot, and businesses had revamped services to make sure they raked in more NDIS money. He described the practice as widespread and very lucrative.

I believe him. I‘ve personally worked with NDIS providers in recent years and have also witnessed rorting of the system.

Fixing our affordability problem

Curbing higher inflation involves addressing the issues that I’ve mentioned.

On housing, we obviously need to make it more affordable. In a recent article, ‘A speech from the Prime Minister on fixing housing’, I outlined a host of policies to tackle the problem. However, I thought that any individual policies weren’t helpful without an overreaching goal and that the government should have a specific long target for house price growth – I suggested keeping them flat for the next decade.

Why aim for flat prices? Because if wages grew by 3% a year over the next 10 years, it meant houses would become more affordable for more people over time.

And this target would allow for a gradual adjustment in the housing market, without a big dip in prices.

In the article, I suggested a key, short-term fix to get house price growth down was to cut migration. I proposed reducing net overseas migration by half over the next 12 months. In my view, this would ease the pressure on rents, house prices, and inflation.

As evidence, I pointed to Canada which had clamped down on immigration over the past 18 months, and it’s since had a meaningful impact on house prices and inflation.

Finally, the government must get serious about cutting spending by overhauling its NDIS program. Addressing widespread rorting of the scheme could wipe billions from government spending and ease inflationary pressure. If the government can’t do this, then it needs to scrap the program and design a new one.

In sum, though we live in a structurally higher inflation world, Australia has particular issues that are making the problem worse. We need to aggressively deal with inflation lest we turn a temporary problem into a long-term one.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.