“Fellow Australians, I want to address our most pressing national issue: housing. For too long, governments have tiptoed around the problems from escalating prices, but for the sake of our younger generations, that stops today.

First, let me run through what our housing issues are and how we got here.

The biggest problem we face today is that property prices are out of reach for many younger Australians. That’s only a recent thing.

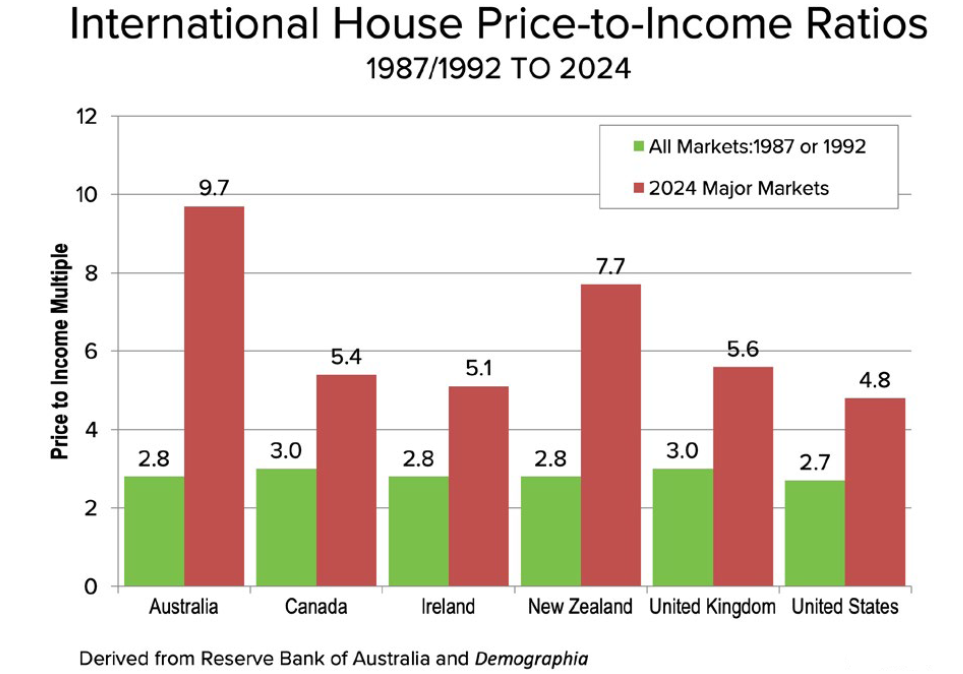

Back in my youth – in the 1980s and 1990s - housing was more affordable. Yes, interest rates were a lot higher then, but those rates consistently fell through those decades, and right up to the Covid-19 period.

In 1987, house prices were the equivalent of 2.8x the annual income of households. Today, that multiple is 9.7x and rising.

According to consultants, Demographia, we now have five of the 15 most expensive cities in the world when measured on a house price to income basis. Adelaide, Brisbane, and Melbourne are pricier than cities like New York and Greater London.

What house prices have done is to increase inequality between generations, and that has increased tensions between those generations.

Some might argue that the young will always have the Bank of Mum and Dad, though let’s not forget that many of them don’t have access to this.

And the broader issue is whether we want to be a society where wealth is passed down from one generation to the next, making it harder for people to move up the income and wealth ladders.

I’d like to think not and that we are still a country that can offer a ‘fair go’ for all.

Unaffordable house prices aren’t just a problem for our younger generations. They’re also an issue for our economy too.

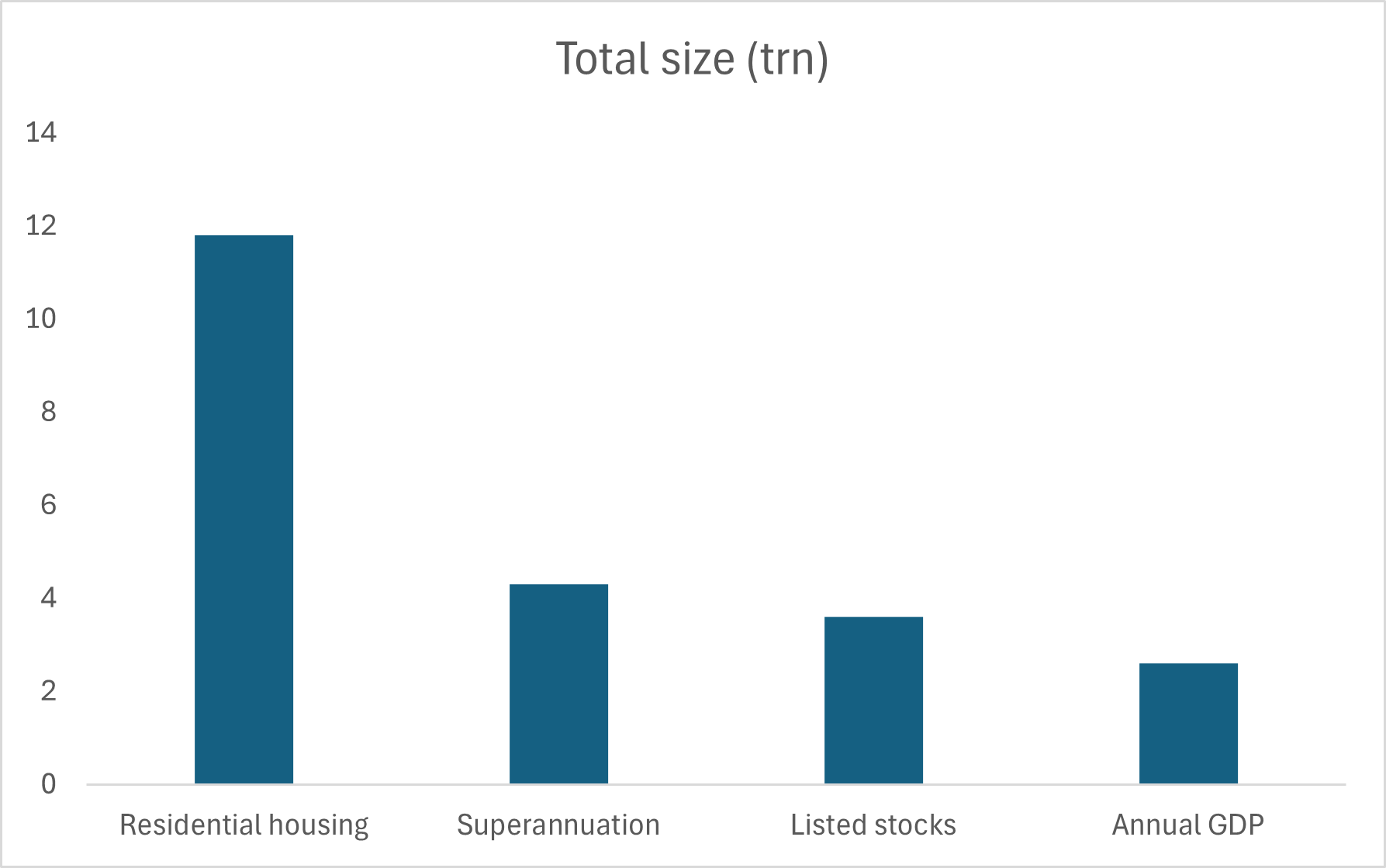

Property is so large compared to our economy that it is almost our economy these days. The latest figures show that residential housing is around 4.5x the size of annual GDP.

Source: Cotality, World Bank, Firstlinks.

We’ve become so reliant on housing that any fall in prices would have a major impact on our economy. That makes our economic prospects increasingly fragile.

Not only that but housing’s dominance means there’s too much money flowing into property and not enough into other areas that have the potential to drive our economy.

More money going into innovative technology, health and other fast growing industries could do wonders for our productivity and living standards going forwards.

So, they are the main problems. You may ask: what’s caused them?

It’s a combination of a lot of things. On the supply side of the equation, it’s obvious not enough housing has been built to keep up with demand. People have blamed NIMBYs, planning regulations, construction costs, and a host of other factors.

However, I think there’s a bigger, neglected issue at play. For decades, Australia and many developed countries have had an overreaching strategy of making cities denser – that is, building more in inner city areas. Yet, that has made only land scarcer and driven up land prices.

When it comes to demand for property, I admit that governments including ours haven’t helped on this front. Tax breaks, first homeowner grants, and increased immigration numbers have juiced demand and prices.

Governments are well intentioned though sometimes what helps people in the short run isn’t always what’s best for the country in the long term.

The mismatch in supply and demand has led to ever-rising prices and it’s got to the stage where housing is treated as much as an investment as it is a place of shelter.

Recent figures show that investors account for around 40% of new housing loans. That doesn’t seem like a sign of a healthy property market.

No doubt you’ll be eager to hear about how my government intends to fix the housing issues.

Well, I don’t think any individual policies are helpful without an overreaching goal. So today, I’m announcing our target to keep house prices flat across the nation for the next decade. You can judge my leadership on how close we get to this goal.

Why aim for flat prices? Because if wages grow by 3% a year over the next 10 years, it means houses will become more affordable for more people over time.

And this target will allow for a gradual adjustment in the housing market. We don’t want a big dip in prices because that would impact current owners and it would put a big hole in consumer spending and our economy. A gradual adjustment seems more sensible.

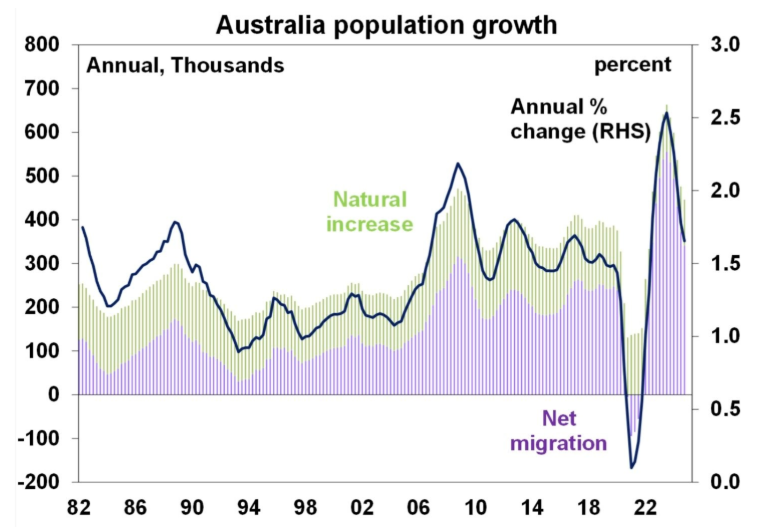

How are we going to achieve this? First, we’re going to address demand by cutting migration.

Last financial year, we had 667,000 migrants come to our shores, up from 464,000 a decade ago. Those high figures have put all sorts of pressure on house prices and rentals.

Source: AMP

We are going to cut that migrant number in half from January for 12 months. This measure should ease demand for both housing and rentals.

Our focus will be on primarily bringing in skilled migrants and temporary ones who have building skills and can help ease construction work shortfalls. Other areas of migration will be cut.

A similar policy has recently worked in Canada, which late last year implemented significant cuts to migrant numbers. Since then, both house and rental prices have marginally fallen across the country.

Don’t get me wrong, immigration has been wonderful for our country for a long time. But, the numbers, especially coming out of Covid, have been high, and it’s time to act on this.

If cutting migration doesn’t work to flatten house prices, then we reserve the right to take further action to reduce demand, and target tax breaks, first homeowner grants, and even bank lending, especially to investors. We’ll roll out more policies until we achieve our aim.

On the supply side, we’re going to continue to increase the building of new homes but we’re going to do it in a smarter way.

The new strategy will emphasise development in outer urban fringes. This is going to be a major task because we’re first going to have to build the infrastructure on these fringes. Especially transport, principally fast trains.

We don’t want people to live in these areas and be forced to commute 90 minutes to get to jobs in the city. We need faster transport to connect homes to employment opportunities. And that’s not to mention building the facilities, schools, shops and so on, to make these areas livable.

We’ll still increase housing in inner city areas though the emphasis will switch to expanding our city boundaries and housing.

There will be plenty of critics to this new planning strategy, though let me reiterate that densifying cities, like we’ve been doing, hasn’t worked to tame house prices.

It’s worth noting that our counterparts across the Tasman have had some recent success with greenfield development in outer urban areas, which has contributed to falling house prices in recent years.

To help with this strategy, we’re going to tie state government funding to quotas for land release, and we’re going to tie government funding for councils to quotas for housing approvals.

Undoubtedly though, increasing supply is a slow burn. That’s why we need to take immediate action to reduce demand, first by reducing migration numbers and then with other policies if needed.

Outside of these housing specific policies, we’re going to ramp up incentives for businesses in fast growing industries. In AI, biotechnology, IT services and infrastructure, and renewable energy. We’ve become too reliant on housing to grow our wealth and we need businesses to pick up the slack. We want to help businesses succeed not only locally, but globally. Hopefully, this increases the flow of money into businesses, at the expense of the housing sector.

All told, I expect to get plenty of feedback about the new measures. From businesses aggrieved by the reduction in migration, which will impact demand for their goods and services. From current homeowners and investors who’ve been used to consistently rising home prices. From people employed in the real estate industry, who’ve benefited from decades of soaring house prices. From universities, about decreasing international student numbers.

What I would say to them is this: the country can’t be run to satisfy a segment of the population; it must be run for what’s best for the whole country.

The situation with property prices is out of control and major action is needed. Making housing affordable for younger generations is this government’s number one priority and we won’t stop it until we make it happen.

Thank you for your attention and good day.”

*To be clear, Anthony Albanese did not make this speech, though I wish he did. It's purely the work of my imagination.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks, aka Prime Minister for a day.