Following the RBA’s November meeting and its decision to hold the cash rate target at 3.60%, there's been no shortage of commentary about what's coming next. One more rate cut by May? Two more rate cuts by August? Rate increases? Some even incorporate predictions about AI adoption and productivity gains – but can we rely on these long-range forecasts?

Economic forecasting is as much an art as it is a science, and a forecast is almost always wrong. As economist Rudi Dornbusch put it – “in economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could”.

The RBA’s 2021 forecast on interest rates

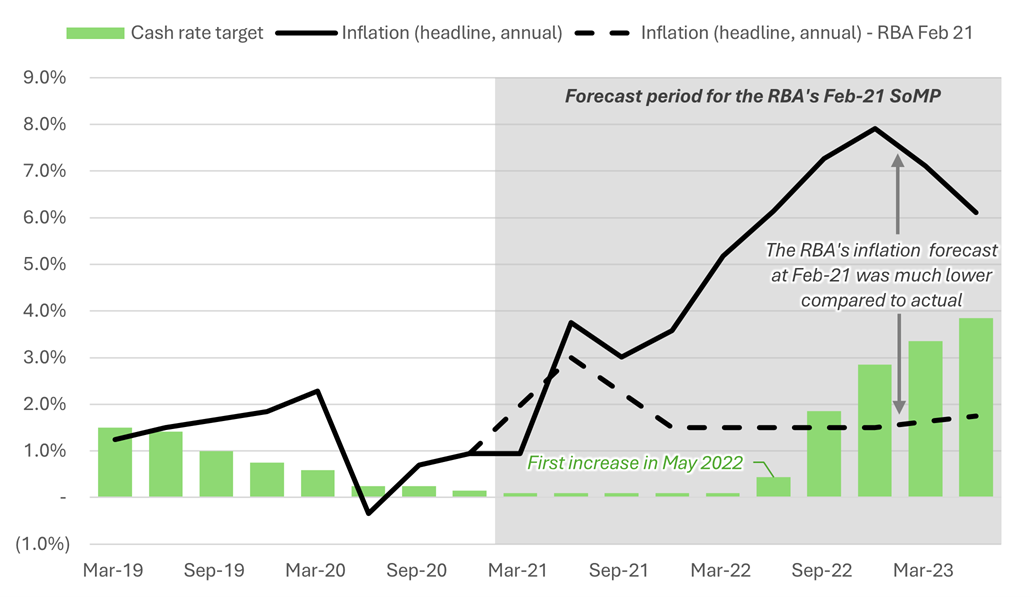

At its February 2021 meeting, during the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic, the RBA decided to keep the cash rate target at a record-low 0.10%. While noting Australia’s early economic recovery was “stronger than was earlier expected”, the RBA believed the economy would still face high unemployment and low wage growth for some time, keeping the overall economic recovery (and, subsequently, inflation) subdued.

In fact, the RBA specifically considered that conditions in the labour market wouldn’t turn favourable “until 2024 at the earliest”.

Dr. Philip Lowe, then Governor of the RBA, reiterated this judgment in March 2021 at the AFR Business Summit, stating that “the cash rate is very likely to remain at its current level until at least 2024”.

As Figure 1 shows, this prediction turned out to be very wrong.

Figure 1: Inflation and the cash rate target in Australia following the RBA’s Feb-2021 meeting

Source: ABS, RBA. Values measured on a quarterly basis. RBA forecast interpolated to quarterly values. ‘SoMP’ refers to the RBA’s Statement on Monetary Policy.

After the first increase to 0.35% in May 2022, the RBA increased the cash rate target another 12 times to 4.35% by the start of 2024. Many were quick to point the finger at the RBA (or, specifically, Dr. Lowe) for ‘misguiding’ them on what would happen to interest rates.

I think instead that there was misunderstanding about how to both communicate and interpret forecasts, particularly in the complex world of economics.

Despite all the science, there is still an art to forecasting

Dr. Lowe, in his final speech as RBA Governor, said of that infamous 2021 prediction: “that guidance was widely interpreted as a commitment, rather than a conditional statement”.

“Conditional” is key here – most economic forecasts are conditional on something else happening. Think of the classic YT=A+BXT model – our estimate of Y in any period T is based on what X is. If X turns out to be very different to what we thought it would be, then our forecast of Y won’t be very accurate.

In the RBA’s case, its February 2021 forecast that interest rates would remain low until 2024 was based on unemployment remaining elevated and wage growth staying low. Obviously, that didn’t transpire.

Without knowing all the details of the RBA’s forecasting process, I’m sure that its forecasts of persistently high unemployment and low wage growth were also based on forecasts of other outcomes that are embedded in the RBA’s economic models – each expectation building on another.

Figure 2: Forecast complexity compounds in economic models

All those other forecasts could have their own data-driven models, but at some point, the ‘science’ of forecasting (the models, the data, the maths, etc.) can only tell us so much. Forecasts are therefore usually a combination of science with ‘art’ – judgment and expertise.

Using the example of our simple model, it may be possible to forecast what X is, perhaps using its own model. But one could make a guess based on judgment or expertise – if X has historically been growing at 1%, then perhaps it’s reasonable to assume that X in T+1 is 1 per cent more than X in T.

In the case of the RBA, its forecasts were based on a judgment about how long the pandemic would last – as Dr. Lowe put it, “we were being told that it would take many, many years for vaccines to be developed, that people could be locked down for a long period of time”.

A good forecast, in my experience, appropriately balances ‘science’ with ‘art’ – a forecast that is based purely on data may over-simplify reality, while a purely ‘gut feeling’ forecast is subjective and prone to personal bias.

Forecasts are point-in-time – and things can change quickly in economics

Of course, even with the best models and data, and the most refined expertise and judgment, what we expect to happen rarely transpires exactly as planned.

The RBA isn’t alone in experiencing this. Just ask NAB, which believed back in May 2025 that the cash rate would decrease from 4.10% to 2.85% by November.

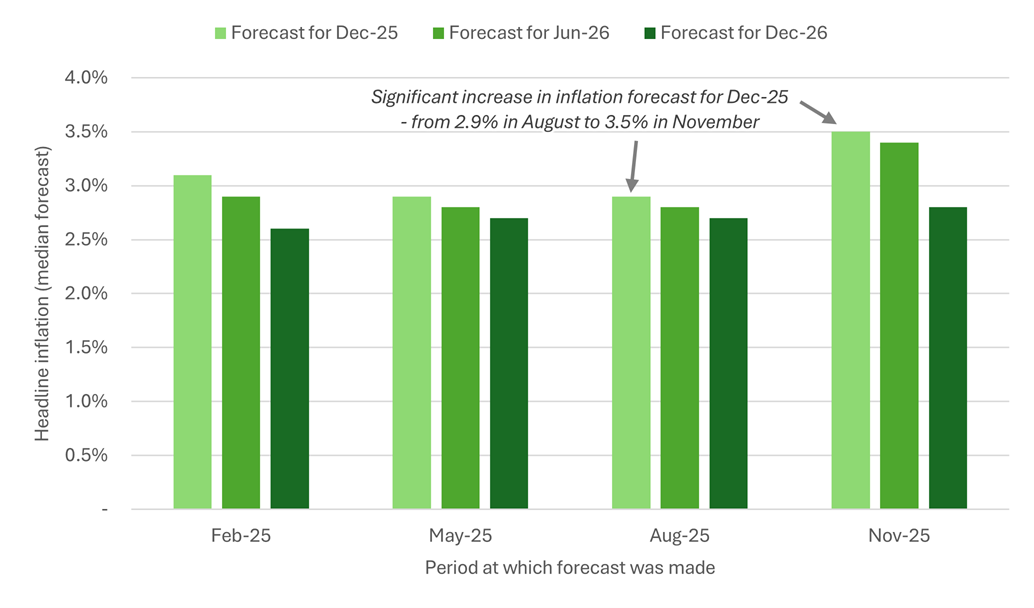

Any of the economists confidently calling for a November rate cut before inflation data for the September quarter was released would also now know this to be true. It was only in August that economists believed inflation by the end of the year would be 2.9%. Come November, that forecast increased by 60bps to 3.5%!

Figure 3: Economist expectations of inflation throughout 2025

Source: RBA.

To be clear – this isn't a criticism of economists or forecasting techniques. It's simply the reality of trying to predict the future in an increasingly complex and volatile economic environment.

What makes forecasting so challenging is that predictions are fundamentally point-in-time assessments. They represent a 'best guess' based on the ‘science’ and the ‘art’ available at the time – current data, current models, current expertise and current expectations.

The interest rate forecasts of NAB and the November inflation forecasts of many economists were all based on some underlying expectations made at the time about what the future economy would look like – that unemployment would be higher, or that inflation would be lower. This is, of course, no different to the judgments made by the RBA back in 2021.

Think of forecasts as the ‘central’ case within a range of potential outcomes

With all these caveats, it’s essential that forecasts are communicated and interpreted correctly, especially when many simply state a belief about what the cash rate is going to be, for example, without offering any other information about what that forecast is based on (or, how wrong their forecasts have been in the past!).

When it comes to communicating or interpreting a forecast, it should be viewed as the ‘most likely’ or ‘central’ outcome expected by the forecaster, based on the forecaster’s use of data, models and judgment.

A forecast should be considered within a range of other possible outcomes that sit around it – they ‘fan’ out from that central case, with the width of the ‘fan’ a function of probability or confidence. Forecasts with lower prediction confidence would have a relatively wider fan of possible outcomes, reflecting inherent volatility and uncertainty.

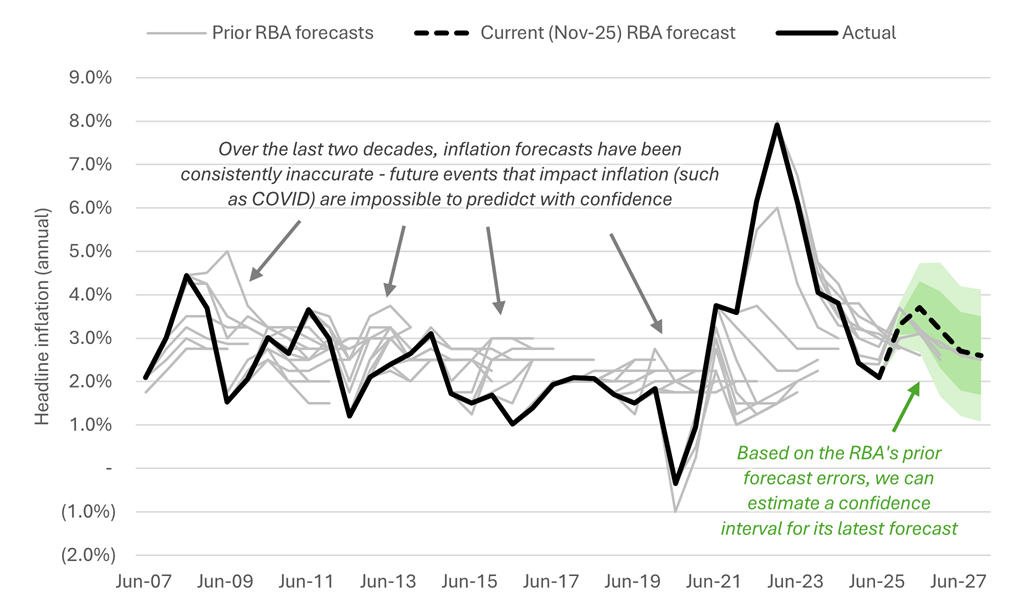

Take the RBA’s current inflation forecasts as an example. In its November Statement on Monetary Policy, the RBA expects, based on current economic conditions and expectations for the future, inflation from December 2025 will rise from 3.3% to 3.7% by mid-2026, before falling to 2.6% by the end of 2027.

This is the RBA’s ‘central case’ for inflation. And while it doesn’t explicitly provide a range, we can still manufacture one based on the RBA’s historical error in forecasting inflation.

Since 2007, the RBA's median absolute error in forecasting headline inflation one period in advance has been around 20bps.1 That error increases to 60bps for forecasts over two periods and 90bps for forecasts over three or more periods.

We can reasonably expect that, based on previous forecast error, the RBA’s forecast of inflation being 3.7% by mid-2026 could have a range of between 3.1% and 4.3% (see Figure 4). If we take the 75th percentile absolute error instead of the median, that range extends to between 2.7% and 4.7% by mid-2026, and between 1.7% and 4.7% by end-2026.

Either side of that range represents a starkly different inflation outcome, with starkly different monetary policy responses. If inflation drops to 1.7%, we'd likely see aggressive rate cuts to stimulate the economy and bring inflation back toward the target band. If it climbs to 4.7%, the RBA would probably be increasing the cash rate to cool things down.

Figure 4: Actual and forecast inflation in Australia

Source: ABS, RBA, author’s calculations. Confidence interval based on median and 75th percentile absolute percentage error in the RBA’s headline inflation forecasts since February 2007.

If forecasts are rarely right, why do we need them?

Despite inaccuracies (especially, in the case of interest rates and inflation, for anything longer than 6 months in advance), good forecasts still give us valuable guidance for thinking about possible scenarios and help us prepare for different outcomes. The RBA's forecasts in particular offer crucial insights into the central bank's thinking and priorities, which may influence how they'll respond to new data as it emerges.

But treating any single prediction as gospel (even those from the RBA itself) is probably a little too narrow-focussed. The economy is influenced by countless factors that, despite all the ‘science’ and ‘art’ we can employ in our forecast models, we simply cannot accurately predict – global events (the COVID-19 pandemic), domestic policy, supply chain disruptions (remember the Ever Given?), and geopolitical developments.

The key isn't to forecast perfectly – it's to understand the range of possibilities and plan accordingly. And for all those possibilities, understanding the confidence intervals, assumptions, data and approach are critical.

So, the next time someone tells you when the RBA will cut rates, or by how much, remember: forecasting is educated guesswork, not fortune-telling. Even the experts with the best data and most sophisticated models regularly get it wrong – it's simply the nature of predicting economic outcomes in an uncertain world.

1 As an aside, the RBA has fared better than economists in general in forecasting inflation, particularly in the shorter-term – a median absolute error of 20bps vs. 35bps.

Jackson Hrbek is an economist and data analyst with ConnellGriffin. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information.