Our clients are getting older. I guess we all are. But in an SMSF, older clients face different challenges. One we’re being asked about a lot at the moment in particular goes something like this:

An example

Ted is 80, a widower. He’s the only member of his SMSF and it owns a property worth $2.4m (the fund bought it a while ago for $1.7m). It has been a strong performer for him in terms of growth (around 5% pa over the long term) and income has typically been around 3% pa (after costs).

He’s in pension phase (his pension balance is $2m) and until now, he’s been able to fund his pension payments from existing cash reserves (the income from the property alone isn’t enough). But now the fund only has $300,000 in cash (earning 3% pa) and he can see that approach won’t last for much longer.

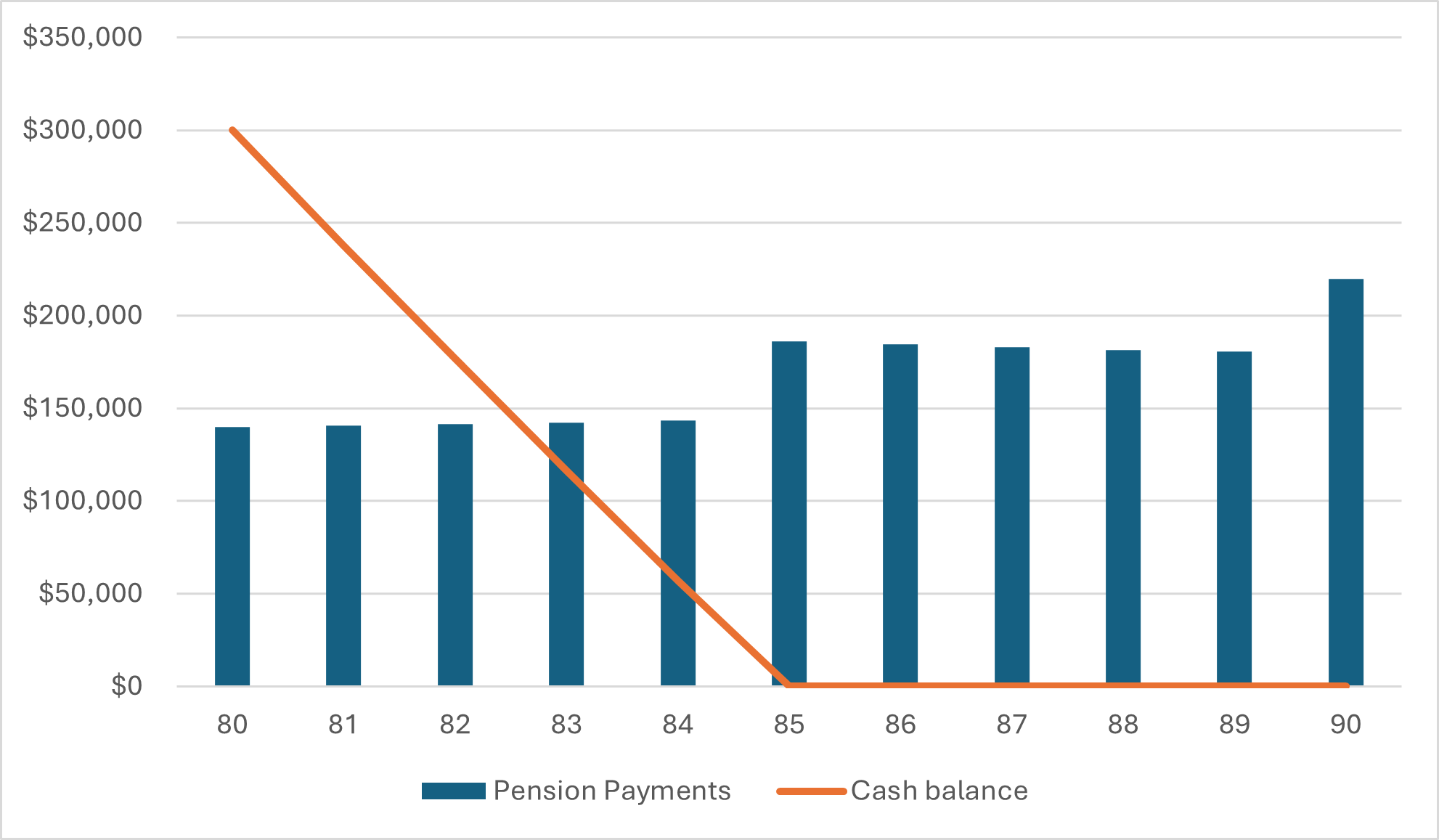

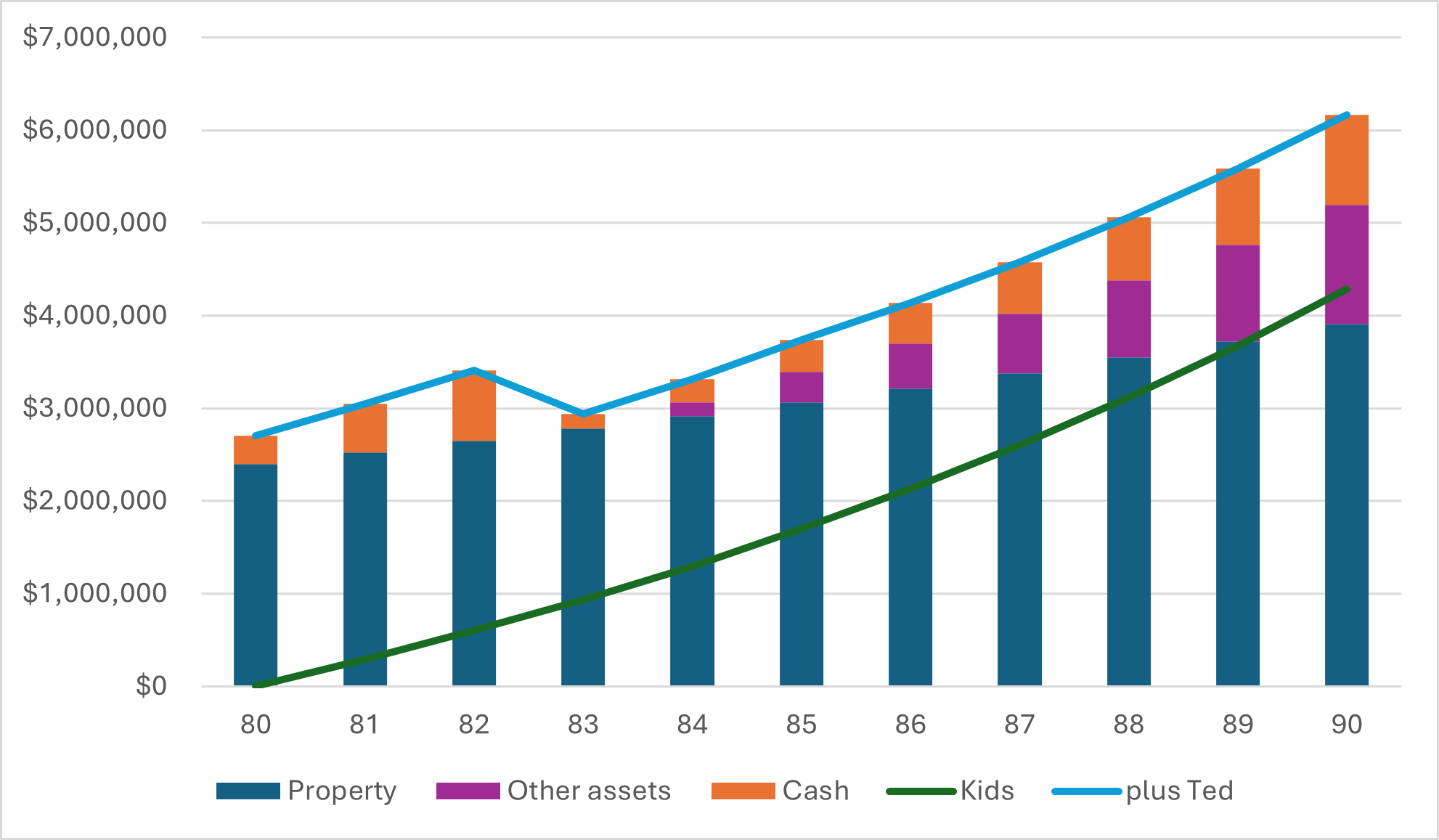

A simple projection looks like this:

Ted’s fund won’t have enough cash in a few years to keep paying his pension.

Note – in this graph, and all the subsequent ones, I have completely ignored the impact of inflation (ie, $1 in 10 years is not comparable to $1 today). Normally I would present all these figures adjusted for inflation so they are directly comparable to amounts “today”. But the key issues I’m considering in this article are things like cash flow and the size of Ted’s balance relative to the property. This is something it’s probably easier to see without allowing for inflation.

What other problems does Ted have?

He’s 80 and would ideally like to start running down his super a little bit to avoid death benefit taxes for his two children (sole beneficiaries).

In particular, he’d like to take his accumulation balance out of super – it’s quite large. While his pension is $2m, his super fund has $2.7m overall ($2.4m property plus $300,000 in cash). So his accumulation account is around $700,000.

But drawing down his accumulation account would make things even worse – even if he did it in a complicated way and transferred a 'partial' share of the property to himself.

At the moment, he’s taking advantage of a unique feature of SMSFs : the rental income for the whole property is available to provide cash flow for his pension even though his pension account only “owns” part of it.

As soon as he transfers some of the asset out of super, he will have to split the income between the SMSF and the new owner of 'part' of the property. His fund’s cash inflows will be even lower.

Could his kids help?

The good thing about Ted’s kids is that they’re both in their mid 50s and ready to really double down on their super contributions. They expect to maximise their concessional contributions for the next few years.

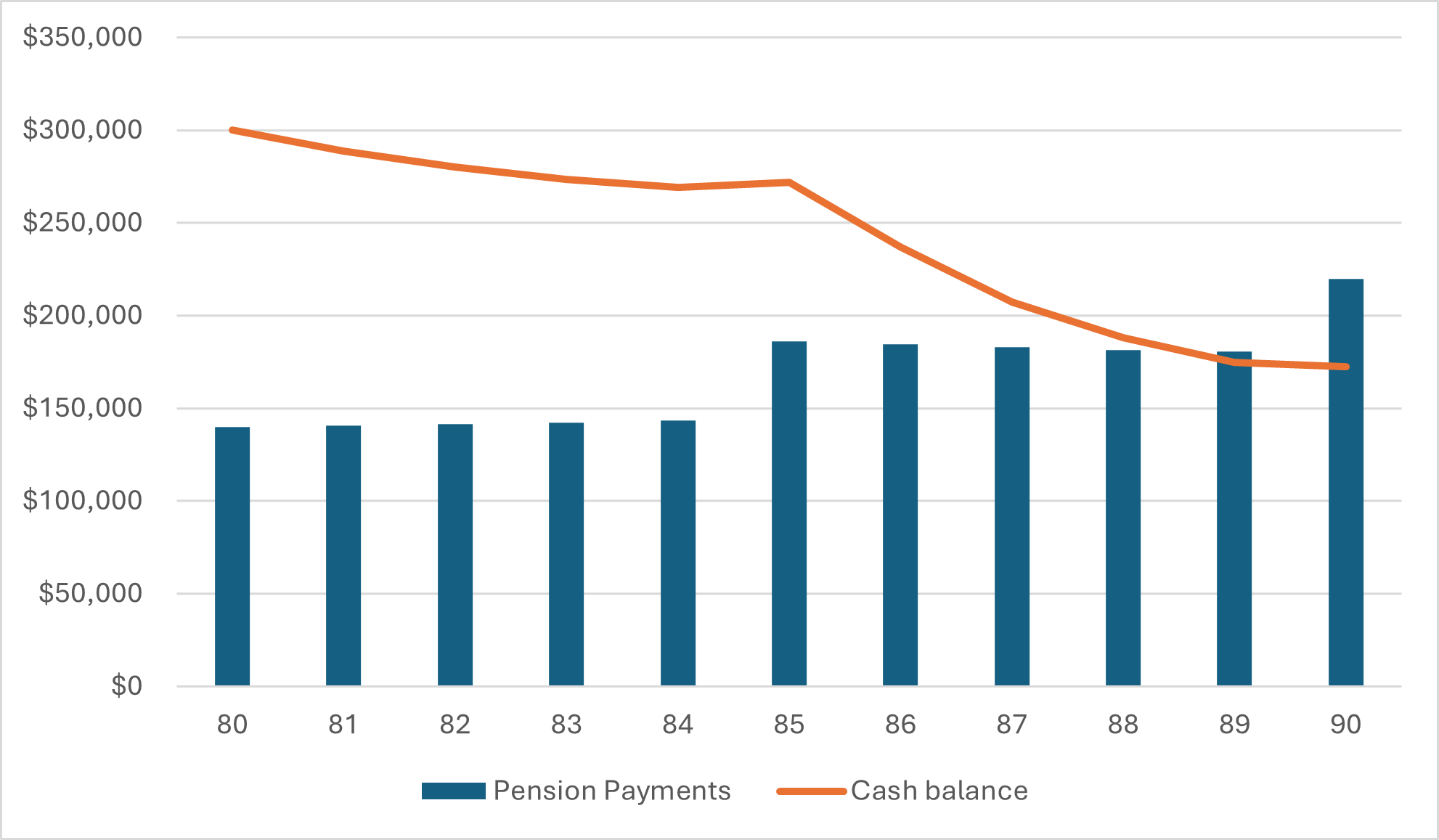

If they were to re-direct the contributions to Ted’s SMSF, would they be able to provide the additional cash flow needed to continue Ted’s pension?

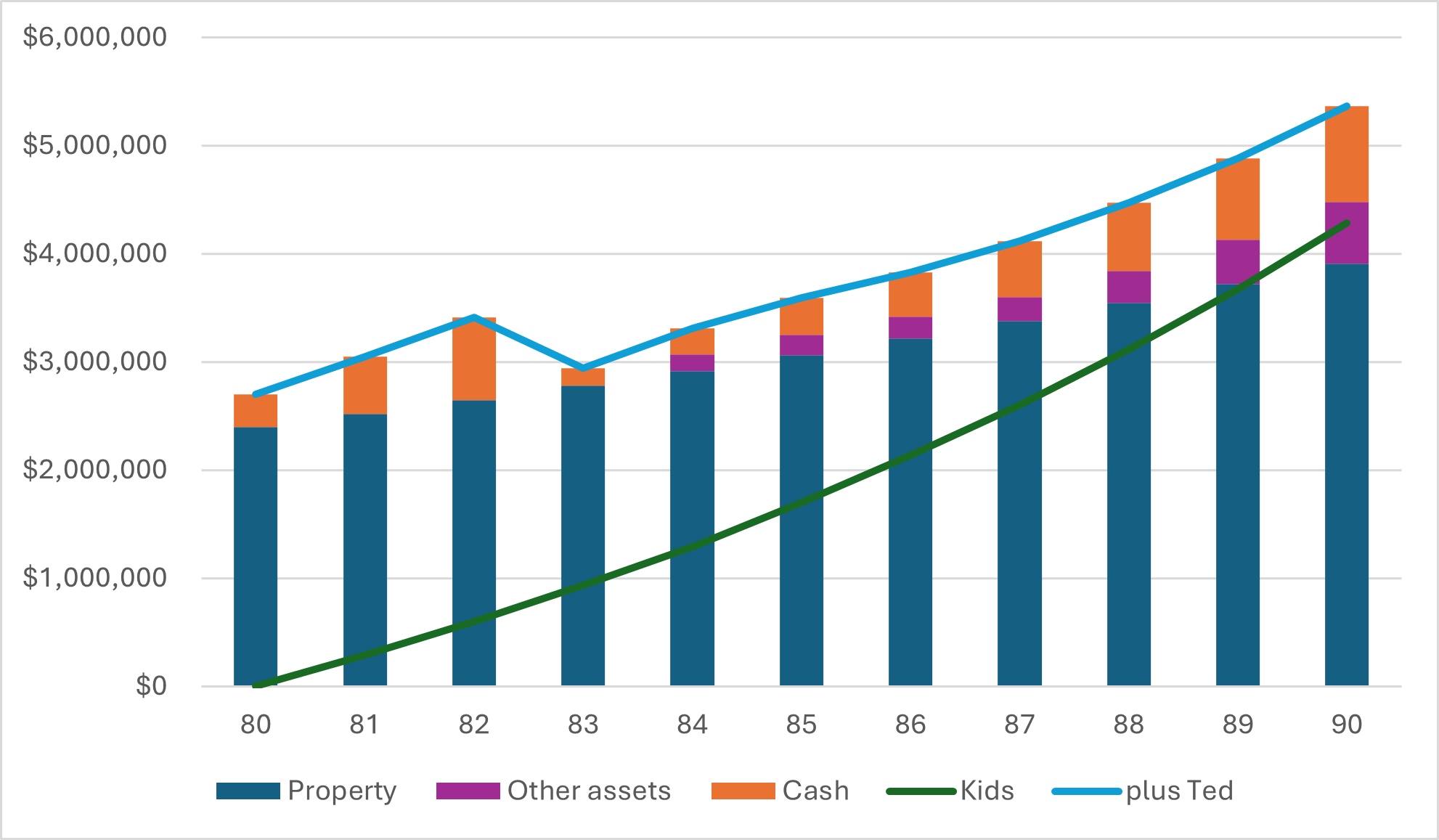

That looks a bit better.

That said, it’s creating another issue. Now the property is shared between the children’s balances and Ted’s.

What will happen when he dies? The Fund will need to pay a death benefit to his beneficiaries and won’t have the cash to do so. Either the property will need to be sold or transferred out of the fund as an in specie death benefit. But that probably won’t quite work either – the kids’ growing balances mean they sort of “own a bit” of the property too now.

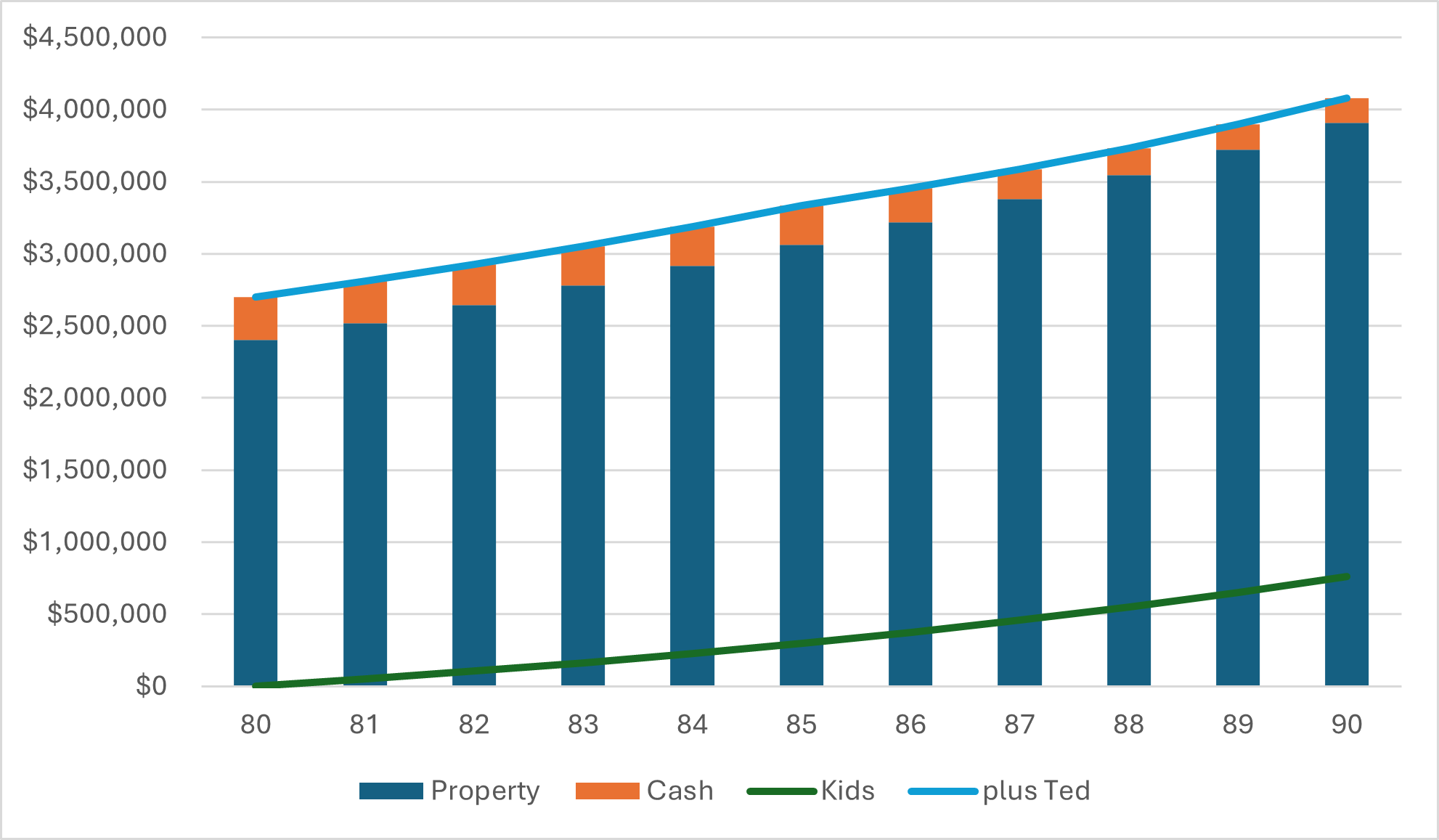

In fact, how do things look over time?

Again – a vastly oversimplified projection is below. The bars show how the fund is divided up (the property in blue and the cash in orange). The lines show how this is divided between Ted and “the kids”. The two sons’ super is represented by the green line and the blue line adds on Ted’s balance (ie, the blue line is the total of everyone’s balances – which is why it matches the top of the bars).

By contributing to the fund, and using that cash flow to fund Ted’s pension, the family has effectively started transitioning the property from Ted to the next generation within the SMSF. But over Ted’s likely timeframe, this hasn’t helped much. It’s allowed the property to remain in super for longer (by providing cash flow) but now we have a bigger problem – how to deal with Ted’s eventual death and pay out his death benefit. The sons’ balances (green line) are nowhere near large enough to absorb the property (blue bar).

Of course, all of this is solved at any time by selling the property but let’s assume that’s unattractive to the family.

What else could we do?

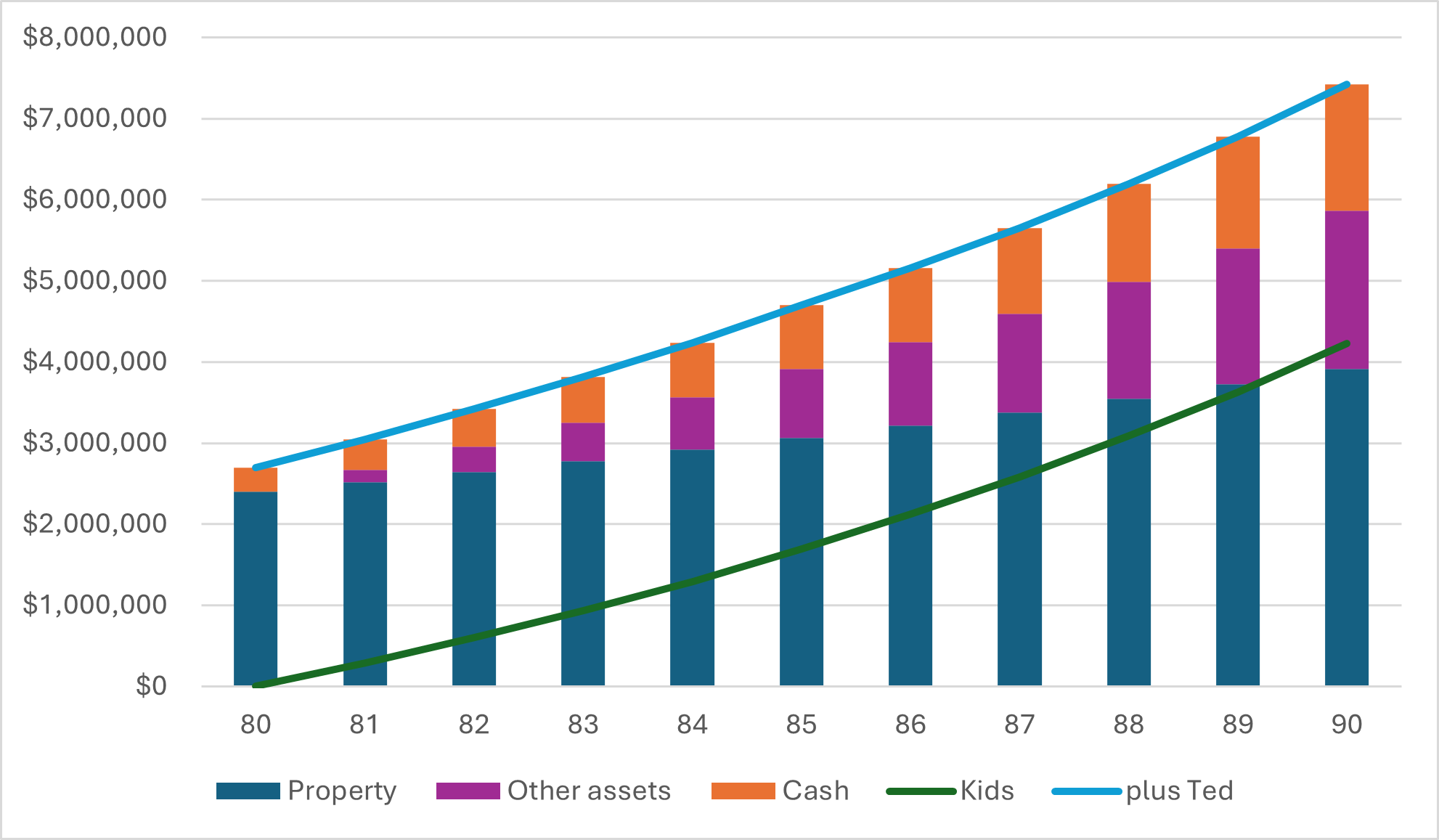

What if Ted’s sons were willing to also make non-concessional contributions?

For starters, let’s imagine they make non-concessional contributions at the level permitted each year (ignoring the complexity of using the special rules to bring forward future years’ contribution caps for the moment).

(We’ll assume they can make these contributions throughout the 10 years – of course if they have a lot of super already they may be prevented from doing this).

Now, there’s a lot more money in the fund. So we’ll assume it’s not all kept in cash – some is invested. But rather than illiquid assets such as a property, it will be used to buy assets that can be sold relatively easily to pay out a death benefit when the time comes. For simplicity, we’ll assume for the moment that this new investment achieves similar returns to the property (3% income, 5% growth).

Since there’s a lot more money in the fund, the scale on this graph is also different to the previous one (see it goes all the way up to $8m).

Now, the sons’ balances after 10 years (green line) are worth roughly the same as the property (blue bar).

But it took a lot! 10 years’ worth of maximised concessional and non-concessional contributions.

What about the sons’ existing super?

Of course, two children aged in their mid 50s would have existing super. They could have reduced their non-concessional contributions if they had added some or all of their existing super to the fund.

That may well be attractive to all concerned, it will depend on their circumstances. For example : are Ted’s sons partnered? And are they already building up super with their partners that they don’t want to disrupt? Does one have more super than the other? (which might make them less keen to bring all their existing super into the fund because one would end up notionally “owning” more of the property than the other).

In some cases, it is “neater” for the family if the transition of the property is managed without touching the sons’ existing super.

In some families, the cash for the non-concessional contributions would even be provided by Ted. In other words, he effectively finances the transition of the property by building up his sons’ super balances.

What about Ted’s plans to wind down his super before death?

So far none of this has helped Ted take money out before death – but perhaps we’ve at least created the environment where he can withdraw his accumulation balance.

Let’s imagine Ted withdraws his accumulation balance as soon as the fund has enough cash to do so. That’s around the 3rd year. See what happens below.

And perhaps we could be even a little more focussed on these withdrawals as the cash starts building up again – taking higher than necessary pension payments from around 83. The graph below assumes normal pension payments for the first 3 years and then doubling them from that point onwards. This is a very deliberate approach to drawing down Ted’s super quickly but not suddenly. It’s risky – what if he dies in the meantime? But at least it allows him to reduce his balance quite a bit and importantly we still reach the point where his balance can be covered by the “non property” assets.

And what happens at the end?

In 10 years’ time, Ted’s sons will be in their mid 60s and presumably looking to start pensions themselves. They would face the same challenges as Ted in that the income from the property won’t be enough to support their pensions over the long term. Of course, they would have the luxury of a bit more time while their pension payments remained low but they would quickly face the same challenges as Ted. Perhaps all we’ve done by moving the problem to the next generation is:

- buy some time, and

- create the environment where the children’s balances (in the SMSF) would be low enough to commence pensions with the full balance (as long as they didn’t have pensions elsewhere) – allowing a tax free sale.

And so?

Of course, the modelling here presents a single fact set with a single set of assumptions. Everyone is different. But perhaps some broad conclusions can be drawn anyway.

For many years, our focus has been on getting as much money into super as possible – knowing it would have to come out eventually. For some people, that strategy has been so successful that we’ve created an entirely different problem – 'eventually has arrived and we need to be prepared for it. Given how difficult it will be for future generations to build up large super balances, and the extraordinary growth in many SMSF assets (particularly property), it is likely that even those with existing plans for intergenerational transfer will need to act early to provide enough time to execute their plans.

Meg Heffron is the Managing Director of Heffron SMSF Solutions, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This is general information only and it does not constitute any recommendation or advice. It does not consider any personal circumstances and is based on an understanding of relevant rules and legislation at the time of writing.

New: The Heffron SMSF 2025/26 Facts and Figures document has been finalised and is available as a free download. Keep it on-hand to access the most recent information to stay up to date.

For more articles and papers from Heffron, please click here.