Should we tax the land value component of property, or the entire property value, including the value of buildings on the site?

On this question, Georgists, who find deep insight in the analysis of 19th-century political economist and philosopher Henry George, come down firmly on the side of taxing land values.

When you tax something, you get less of it.

Since land isn’t going anywhere, taxing the value of land leads only to lower land values. But buildings can go somewhere if you tax the value of the property (land and buildings together); buildings can be built in other jurisdictions, their construction can be delayed, or they can be built at a different density or size.

Because land value taxes don’t change incentives, they are supported across the political spectrum. Right-wing economists like Milton Friedman and left-wing economists such as Joseph Stiglitz all support this tax base for fairness and efficiency reasons.

Wouldn’t it be better to raise more revenue from land and less from people’s work incomes?

I have also long advocated for boosting taxes on land and limiting carve-outs for owner-occupiers. I looked at the progress of the Australian Capital Territory’s (ACT) decade-long transition towards more taxes on land and found the outcomes to be favourable.

But I have also been cautious about substituting one tax on property for another. Stamp duties are a tax levied on property value triggered when a property is sold. But their economic incidence is fully on land (as will be explained later).

Why swap two taxes on property for each other?

Another popular property-for-property tax swap is replacing a property tax (on the value of land and buildings) with a land value tax (on the value of land only).

Is this a good idea? And most importantly, do home and land values go up or down under this tax switch scenario?

Given the popularity of switching from property to land tax, there is a lot of confusion about the likely outcome. Too often, we hear that “land value tax will solve this” without any justification. There is a surprising gap in our collective knowledge, as this X thread from Mike Fellman illustrates.

Let’s dig in and see what we can learn.

Taxes on assets reduce their value

Before we differentiate between taxing property or land, let’s dispel the misleading notion that either tax increases the cost of buying housing.

Think about other assets in the economy, like company shares (stocks).

Let’s be more specific and consider the example of two classes of shares in the same company. Class A shares have no ongoing holding costs. However, Class B shareholders must pay 10% of their market value to the company each year, like a tax.

Will Class A and Class B shares have the same market price, with Class B having an extra cost added on top due to the tax?

No.

The prices of these two shares will differ to account for the difference in expected tax payments.

Class B shares will be discounted relative to Class A shares by exactly the value of the future tax obligations (i.e. the present value of the expected flow of taxes).

This ensures there is no arbitrage in the market—at the prevailing price, the after-tax rate of return for a dollar invested in Class A or Class B shares must be the same.

Assume that both classes of shares earn a $1 dividend per year. Class A shares might trade at $10. With the 10% ‘share tax’ (like property tax) Class B shares would trade at $5.

The $1 per year dividend is a 10% after-tax net return on the value of Class A shares and is also a 10% net return on Class B shares after the 50c 'share tax' is paid (10% of the $5 share value). For each dollar spent on either class of share, you get the same rate of return for the same risk.

How property and land taxes reduce asset prices

Just like our two classes of shares, two identical adjacent homes with two different rates of property or land tax will have two different prices—buyers of the home with the higher tax will factor the cost of the tax into the upfront price paid.

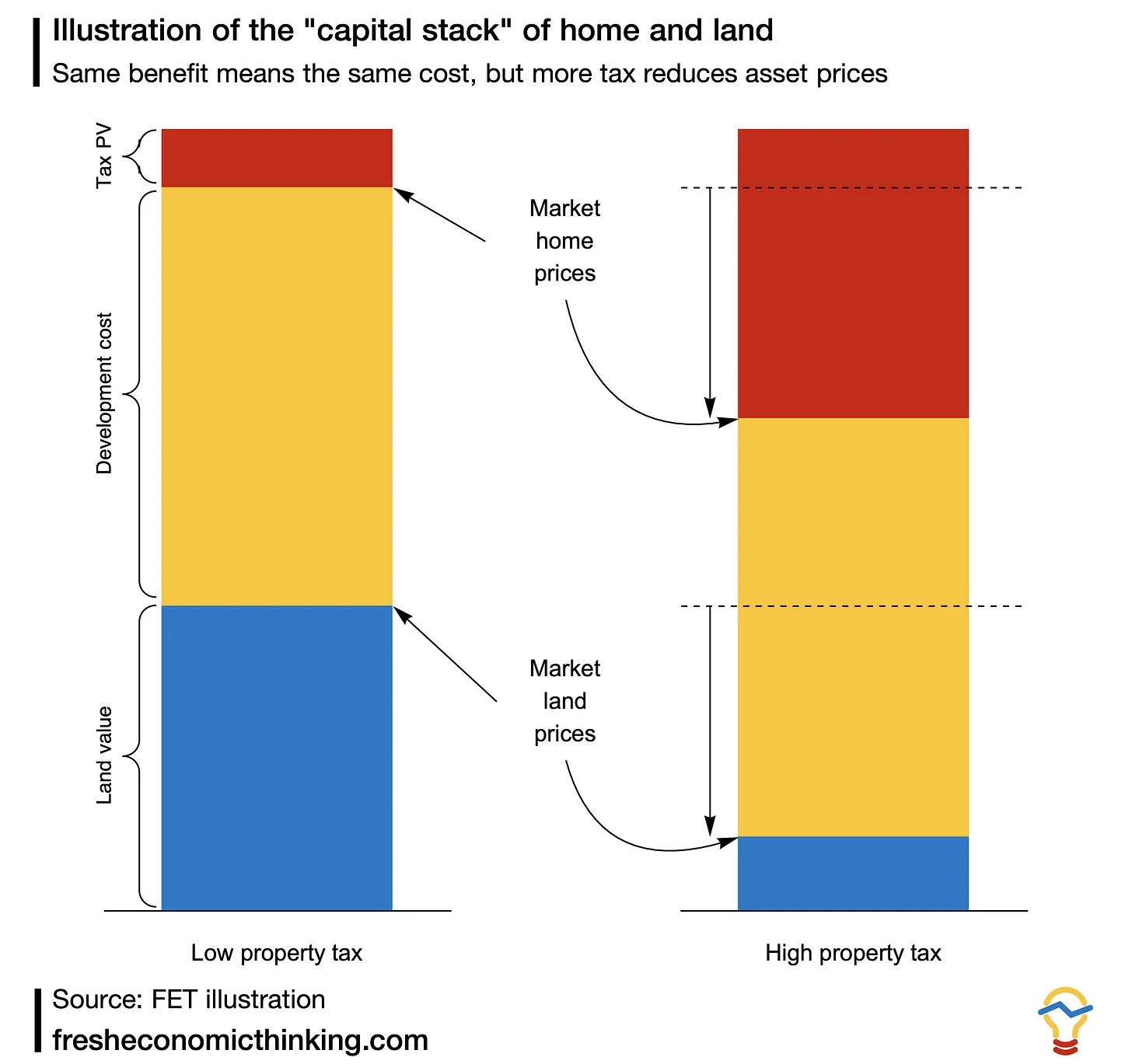

The diagram below illustrates this.

The total height of the two columns is the total present value of the benefits of occupying the home. Buyers will be willing to pay a total cost equal to their total benefits because if there were a gap, another buyer could bid up the price to close it and still be better off from buying the home.

The left column shows a property with a low property or land value tax. The buyers of this property subtract the present value of that tax (the red portion) to determine the net benefit to ownership and pay the seller this value.

The right column shows a property with a high property or land value tax. Here, the buyers also subtract the present value of this higher tax and pay the seller a lower market price for the home (house and land).

Notice that since the construction/development cost of these two identical homes is the same (yellow portion of the bar), the effect of the higher property or land tax is to reduce the land value only.

Both taxes reduce the asset price of land. So when vacant land trades in this market, a tax on land or property will reduce its value by the same amount as the completed home value, which is a much higher proportion of its counterfactual land value under a no-tax scenario.

An example

Let’s put some numbers to the chart above using my home in Brisbane to represent the low-tax left column and see what would happen if a Texas-style 2% property tax were applied.

My home is worth about $1.5 million, with an assessed land value of about $800,000.

I pay $2,900 per year in council rates, which are a tax on land value. That’s a 0.34% tax rate on the land value (i.e. $850,000 x 0.34% ~ $2,900), and an equivalent property tax to raise the same tax amount would be 0.19% (i.e. $1,500,000 x 0.19% ~ $2,900)

Applying a Texas-style 2% property tax will reduce the market price of the property down to $937,000 because of the massive $18,750 annual tax cost. This will push down the land value from about $850,000 to about $287,000, a whopping 66% decline.

The downloadable spreadsheet here allows you to tinker with the effect of land value tax and property taxes on market prices and land values.

The extra tax amount in the Texas scenario, although levied on the value of buildings and land, has the effect of reducing land value without changing the cost of construction.

To raise the same $18,750 annual tax amount from just the land value of my property would require a 6.5% land value tax rate (nearly a 20x higher tax rate than the 0.34% that currently applies).

No wonder often Texas appears cheap in terms of market prices for housing assets—these properties come with huge ongoing tax liabilities. Their relatively high property taxes are equivalent to enormous land value taxes.

Shifting from property to land value tax

Either a property tax or land value tax can be levied on already-constructed properties and the effect is to reduce property and land values.

One big difference between these taxes is what landowners pay prior to development.

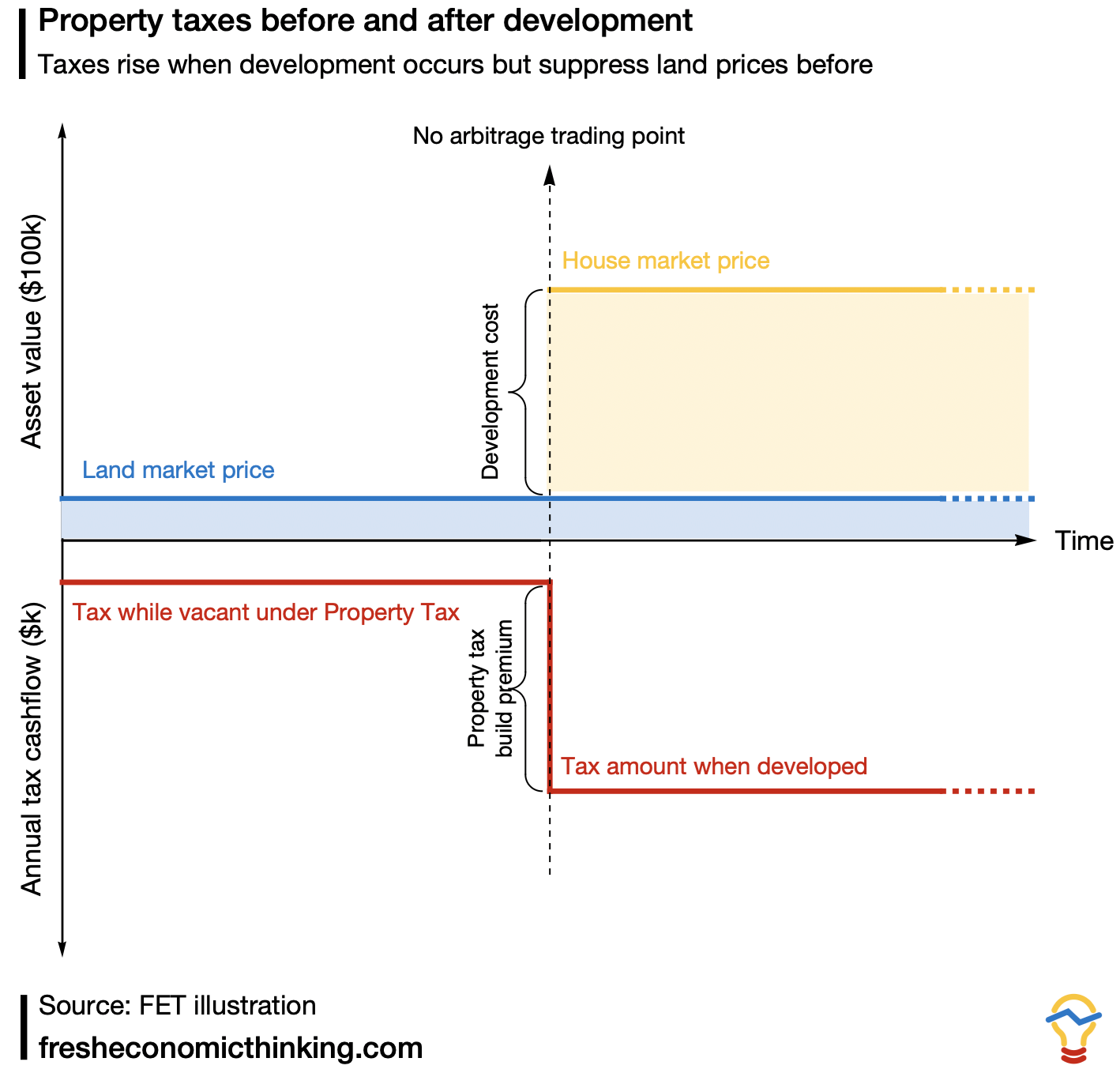

Before building a home, a property tax will apply at the same rate to the land value only. After the home is built, the property tax will be paid at that rate on the value of the land and the new building.

The diagram below shows how the tax amount changes over time before and after housing development.

The no arbitrage trading point in the diagram reflects the idea that a vacant piece of land must have a market value that ensures that when combined with the development cost of a home, there are no surplus returns above the expected risk (which is explained in detail in this FET article).

To put some rough numbers on it, consider an area with a 2% property tax where a typical home is worth $500,000 and home construction is $400,000. This means that the land is worth $100,000. However, before building a home the property tax is $2,000 per year, while after development, it is $8,000 per year, meaning there is a $6,000 annual tax premium for developing housing.

Under a land value tax of say, 6.5%, the amount paid before development would be $6,500, which doesn’t change when a home is built. This lack of change is why most economists argue that land value taxes are neutral in terms of changing decisions about when and what to build.

Do land values rise or fall when shifting from property to land value taxation?

With all this background in mind, we can now get to the heart of the question we initially asked: what happens if we shift from a property tax to a land value tax that raises the same revenue?

Does shifting the tax base to land make the land value go down as our intuition might suggest (i.e. tax land value, get less land value)?

No. It doesn’t.

If the same total tax revenue is sustained, but the base is shifted from property value to land value, then land values will rise, not fall.

Raising the same amount of total tax revenue from a land tax as was raised from property tax will, on balance, involve less revenue from developed homes and more revenue from large vacant or underdeveloped sites.

Less tax revenue from developed homes will increase home values. An increase in home values, without any change to development/construction costs, means an increase in land values by the same amount, and hence by a greater proportion (as we saw earlier).

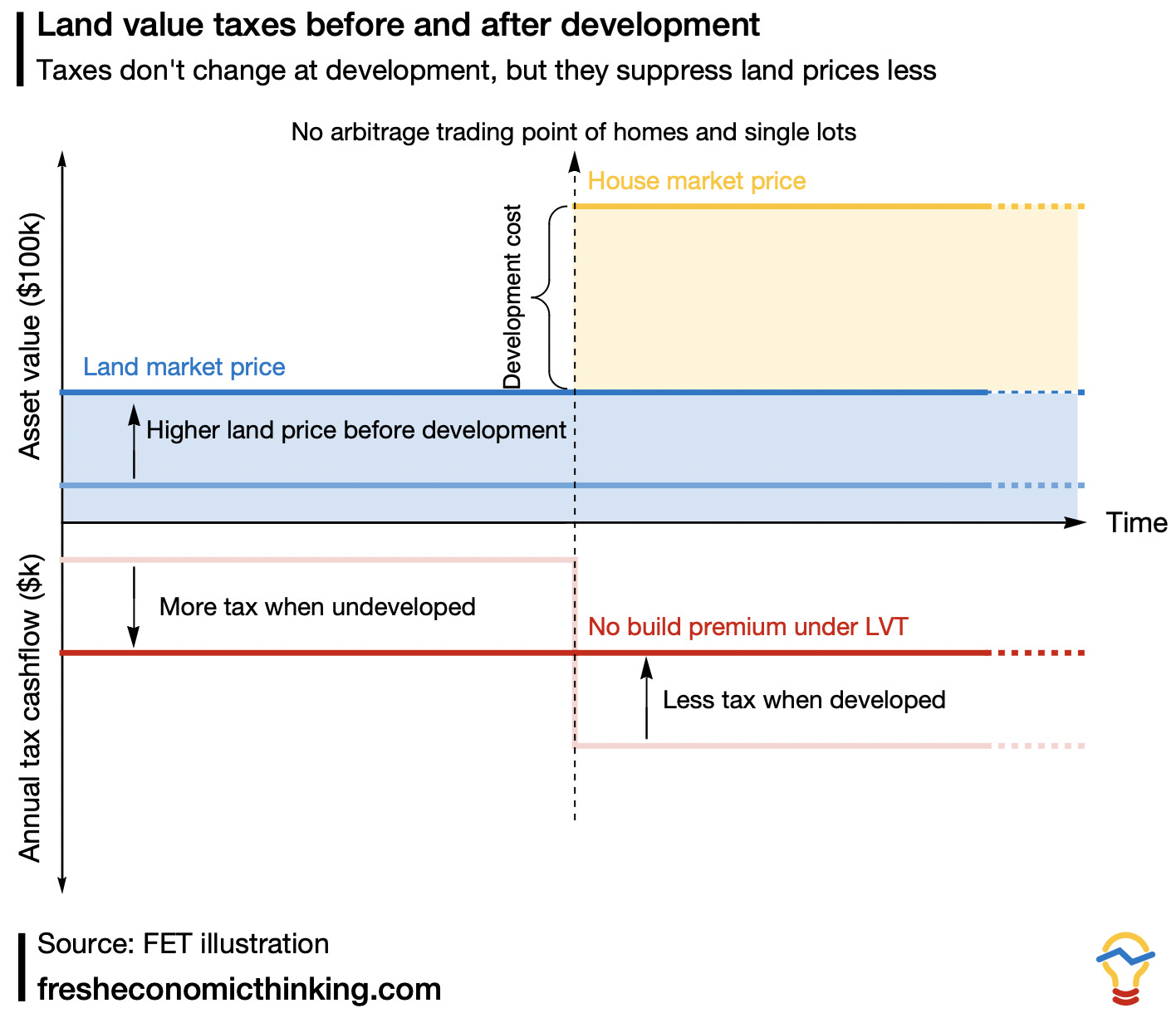

I have tried to visualise this effect in the diagram below.

The lighter colours show the land value and taxes under property taxation. The stronger colours show the new scenario raising the same revenue from a land value tax base. The house price is higher due to lower taxes (yellow line) and the construction cost is the same (yellow area) hence the land value is higher under the land value tax.

However, the tax amount paid is the same for landowners before and after development, unlike under property tax.

Here’s where things get a bit subtle about the distributional effects of this tax switch.

The value of undeveloped large subdividable lots is derived from the value of each single housing lot that the site can produce, so owners of large undeveloped parcels of land face both

- rising market values for the lots able to be subdivided from their land, and

- rising tax obligations.

The tax shift provides these owners with a benefit, in the form of higher land value, as well as cost, in the form of extra taxes before development. This opens up an interesting question.

Is it possible that owners of large undeveloped land parcels are equally well off, or even better off, financially when shifting from a property tax to a land value tax?

In other words, do the benefits of rising market values of land outweigh the costs of higher taxes?

Here’s an example with some numbers attached to get a feel for the possible outcomes (I will dig deeper into this question in future articles).

Imagine a city or state has two properties—one is my house, and one is an adjacent vacant lot.

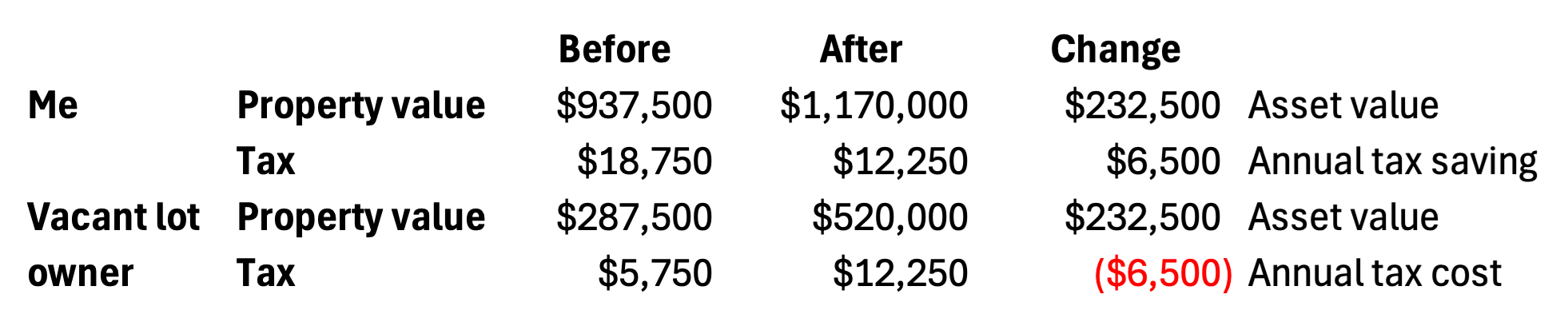

As we saw earlier, a Texas-style 2% property tax makes the market value of my home $937,000 and generates $18,750 of annual tax revenue. That same tax rate on the vacant lot next door with a $287,000 land value would raise $5,750.

That’s a total tax revenue of $24,500 in our make-believe town with one house and one vacant lot.

When we shift to a land value tax, that means setting a tax rate that raises $12,250 (down from $18,750) from my house, and the same amount from the vacant lot next door (up from $5,750).

The land value tax rate that does this is 2.36%. At this tax rate under the scenario in the above downloadable spreadsheet, the adjustment to a lower tax rate involves increasing the market price of the home from $937,000 to $1,170,000 (about 25%) and in the process, increasing the market value of the land from $287,000 to $520,000 (about 80%). The 2.36% land value tax on the land which is now worth $520,000 gives the $12,250 of tax revenue.

In this example, the cost to the buyer is the same. They pay a higher price but get a lower tax, but the all-in annual cost to buy is the same.

What about my neighbour with a $287,000 vacant lot paying $5,750 in property tax? Now, they have a $520,000 vacant lot paying $12,250 per year in property tax.

They got about $230,000 of land value in exchange for $6,500 per year in tax. Given prevailing yields, this cost is exactly equal to the benefit in present value terms (in reality the relativity of costs and benefits to owners of undeveloped land depends on the proportion of developed and undeveloped land in the tax administration region).

Shifting to taxing land values leads to higher land values, not lower values, as many might assume when they say, “land value tax will solve this”.

A similar analysis by Jan Brueckner back in the 1980s, showed that taxing property less and land more will increase land values, noting that “the level of improvements per acre rises, as does the value of land”. In other words, property taxes lead to lower density and lower land values, while land value taxes lead to higher density and higher land values.

The only way to switch from a property tax to a land value tax without raising the market price of homes and land is to levy a land tax at a rate that raises much the same revenue as the property tax for typical homes.

In our example case, the land value tax would need to be 6.5% per year, which would raise the same $18,750 from the existing home, but also $18,750 from the owner of the undeveloped housing lot next door. This would raise $13,000 more total tax revenue, all coming from the owners of un- or under-developed land who pay a lot more tax but get no benefits in the form of higher land values.

Of course, if more tax comes from land, this extra land tax revenue can be used to reduce other taxes in the economy, such as taxes on income. With higher after-tax household incomes, people will pay more to rent and buy homes, leading again to higher land values, which will be taxed. This feedback whereby taxing income less and land more allows the same revenue to be raised from the land tax is described by Georgists with the phrase all taxes come out of rents (ATCOR).

So what?

We often hear that taxing land values will solve just about everything. But like any rigorous economist, we must interrogate such claims, especially so when land value taxes are intended to replace other similar taxes on property.

Yes, land value is a fair thing to tax, and such taxes don’t face many of the implementation and incentive problems involved in taxing things like personal income. But this is also mostly true of property taxes, which also come out of land values (since land values are derived from the returns from use when developed) and are levied at a lower rate on the broader base of the value of land and buildings combined.

Focussing on swapping two good taxes that are incident on land seems like a strange priority to me, especially when a likely result is higher market prices of homes and land with the same total purchase cost for homebuyers (higher price but lower tax).

Dr Cameron K. Murray is Chief Economist at Fresh Economic Thinking. The original article can be found here. Subscribe to his written work at Fresheconomicthinking.substack.com. This article is general information.