Bond markets are in a new regime – ‘safe havens’ are no longer acting as such, and investors can no longer expect asset classes to behave as they have done historically. As a result, asset allocation approaches need a reboot, and portfolio diversification has never been such a virtue.

The new market regime

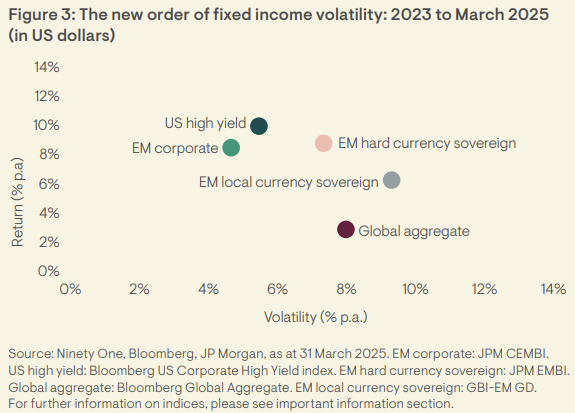

One thing that’s clear from the recent market turmoil is that asset classes are not behaving as they should. Traditional ‘safe haven’ debt markets have entered a new (higher) volatility regime, while supposedly ‘risky’ areas of the market have shown surprising resilience. The once distinct line between developed market (DM) and emerging market (EM) assets appears to have blurred. This, together with other macroeconomic and geopolitical shifts, has profound implications for asset allocators.

Unexpected behaviour in bond markets – a blurring of lines

Back in 2022, we began alerting investors to an apparent regime shift in bond markets. Recent market events suggest this is more than a fleeting move – a fundamental shift appears well underway

In recent years, the volatility of asset classes traditionally viewed as risk-free, such as the UK Gilt, German Bund and US Treasury markets, has shifted gear. In fact, considering the behaviour of both the EM and DM asset classes from a risk and return perspective, there appears to have been a blurring of lines – a phenomenon we refer to as the ‘EM-ification of DM’.

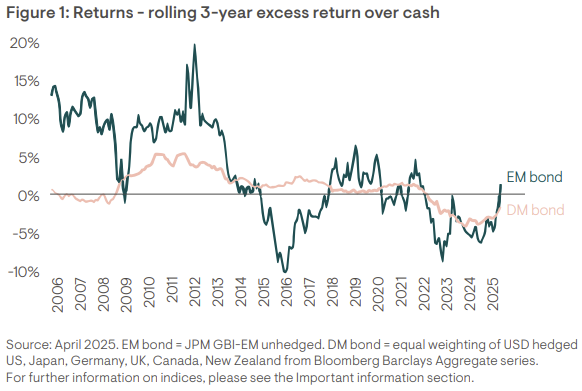

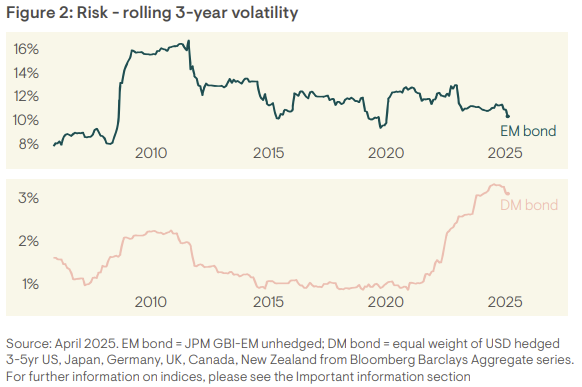

Since 2022, returns have been lacklustre in DM bond markets, while EM bonds have shown surprising resilience (Figure 1). Meanwhile, volatility in the EM bond market has remained within its historical ranges, but in DM it has risen sharply (Figure 2). Furthermore, there have been episodes of bear steepening in DM yield curves, which reflect concerns around policy credibility (as noted here) – an unenviable phenomenon traditionally reserved for EM bond markets.

Driving forces behind a shift in asset class behaviour

Three broad developments – across EMs and DMs – help to explain a shift in DM bond market volatility and blurring of lines between DM and EM bond market behaviour:

1. Orthodox monetary policy in EMs

Despite the headwind of relentless US dollar strength – plus the negative impact of Russia’s local currency debt being written down to zero in 2022 – the EM debt asset class has shown resilience. This is largely thanks to orthodox monetary policy in many EM economies, with EM central banks wasting no time in embarking on interest rate-hiking cycles when inflation began to rise post-COVID 19. In contrast, some of the world’s largest government bond markets have suffered from delayed action by DM central banks, which deemed higher inflation to be a ‘transitory’ phenomenon, meaning the eventual rate-hiking cycle was possibly faster and more pernicious than the path followed by EM central banks.

2. Fiscal restraint in EMs

In stark contrast to some of their DM peers – where fiscal discipline has eroded in recent years – fiscal fundamentals in many EM economies have strengthened over the past decade. Spurred on by the upheaval of the 2013 taper tantrum, which exposed underlying economic imbalances, many EM economies have undergone a significant rebalancing, strengthening their resilience. Even after the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, many EM policymakers remained fiscally prudent, resulting in primary fiscal balances returning to surplus within just a few years and debt-to-GDP stabilising at modest levels. Today, there are some great examples of sound economic stewardship across the EM investment universe, with Argentina now an unlikely poster child in this regard (fiscal discipline and reform are turning around the Argentine economy).

The fundamental improvements in EM economies are fuelling an improvement in rating dynamics. Combining the outlooks of S&P, Moody’s and Fitch, ratings upgrades in 2024 outstripped downgrades across EM regions. Furthermore, this positive trend looks set to continue: at the time of writing, 44 EM countries are currently on positive outlook, compared with 32 on negative outlook.

While there are notable exceptions, credible policymaking and fiscal reform are unmistakable trends in EM economies, and this is reflected in increased resilience.

3. Less certainty around policymaking in DMs

‘Political instability’, ‘rising populism’ and ‘unsustainable public finances’ are terms traditionally associated with EM countries, but they have become increasingly common descriptions for some of the world’s largest and most ‘developed’ economies in recent years.

While each country’s political backstory is unique, the common theme is a pronounced deterioration of macroeconomic fundamentals. Today, glaring fiscal imbalances in some ‘advanced’ economies suggest the world order has been turned on its head, with little sign of this reversing materially. All of this speaks to a much less predictable policymaking backdrop in DM economies, equating to a more uncertain macroeconomic outlook, and necessitating increasing caution by – and risk premium for – investors.

Has DM debt lost its defensive properties?

In addition to entering a new volatility regime, DM debt has also seen its role as a defensive portfolio allocation put to the test.

Over the past few decades, the economic community has generally become accustomed to dealing with ‘demand shocks’ – disruptions to aggregate demand, with the Global Financial Crisis a prime example. Analysing demand shocks, and policy responses to them, is relatively less complex than analysing supply shocks. Furthermore, the asset-class implications were predictable: when growth fell, lower inflation would follow, meaning fixed income behaved well as a defensive asset. But in the past 5-10 years, the nature of shocks hitting the global economy has changed. We have seen a series of ‘supply shocks’ – including Brexit, COVID-19, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and trade tariffs. These are exceptionally hard to quantify and have resulted in growth and inflation moving in opposite directions – i.e., lower growth and sticky inflation. That has led to higher correlations between defensive and cyclical assets; in this context, DM bonds have been less able to shield investors from equity market losses.

Put another way, the shift from demand to supply shocks has changed the nature of interest rate risk and its relationship with risk assets, meaning it’s not as helpful for managing a balanced portfolio as it used to be.

This shift has not gone unnoticed by policymakers; Fed Chair Powell recently noted: “We may be entering a period of more frequent, and potentially more persistent, supply shocks — a difficult challenge for the economy and for central banks”.

Implications for asset allocators

Time to recalibrate asset-class perceptions

All of the shifts outlined above point to the need to view DM debt markets in a different light when considering portfolio allocations.

The same can be said for EM debt, where perceptions are often outdated. As we outlined here, much has changed since so-called Brady bonds were first introduced in the late 1980s – when yields were sky high, liquidity was scarce, and most debt was dollar-denominated. Credible monetary policy in EM economies has underpinned the development and significant growth of the EM local currency debt market, and the volatility of the benchmark has fallen with the inclusion of more Asian markets, with somewhat lower yields today reflecting the higher quality of the asset class.

A major headwind to EMs is retreating

Taking a more forward-looking perspective, asset allocators need to question whether their experience over the past decade is likely to be repeated. The path of the US dollar is crucial, in this regard. The US dollar strength that has prevailed over the past decade, casting a shadow over EM asset-class returns, is arguably fading. While the US economy has dominated global growth in recent years – resulting in US assets attracting the lion’s share of inflows and the US dollar going from strength to strength – the investment and inflation outlook for the next decade is likely to mean a more even distribution of nominal growth across the globe.

With the US dollar unlikely to follow the same path as the past decade, and the US dollar shadow fading, EM debt deserves to move back onto asset allocators’ radars.

A different decade lies ahead

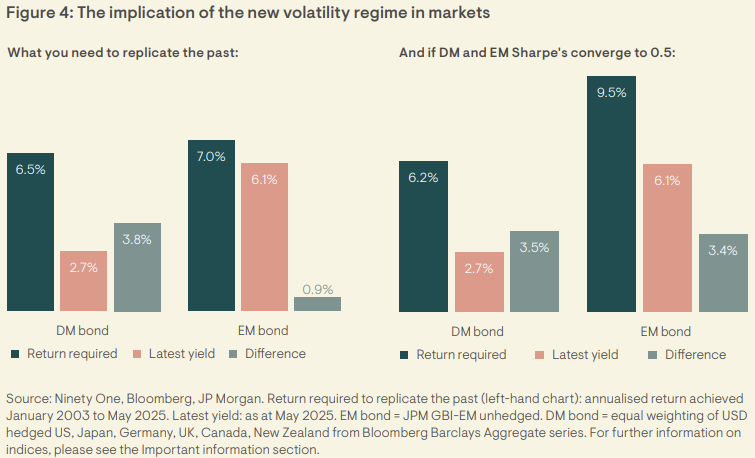

While asset allocators’ experience will differ according to region and portfolio specifics, the framework below serves as a stylised example of what the new regime in DM bond market volatility means for asset allocators.

Heightened volatility in the DM bond market shifts the risk side of the risk/return equation. That means higher returns are now required to replicate past experience. Furthermore, if investors want to achieve the same Sharpe ratio from their DM and EM allocations as they have done historically, lower current yields point to a much higher capital gain requirement in DM; in contrast, yields in EM should provide the majority of what’s needed (Figure 4).

However, it seems reasonable to conclude that DM bonds will struggle to replicate historical outcomes. The next decade is likely to be more favourable for EMs as the rallying US dollar headwind begins to weaken and structural themes such as deglobalisation, the energy transition and demographics impact market behaviour.

Diversification has never been more important

Shifts in asset-class behaviour, coupled with the changing nature of economic shocks outlined above, mean the case for portfolio diversification has never been stronger. Crucially, a ‘far and wide’ approach may be needed when diversifying. And this is not just about picking winners; it’s about avoiding losers, especially in today’s geopolitical reality.

Importantly, asset allocators need to look at diversifying across new dimensions. In the past, diversification was thought of in terms of regions, currencies, asset type (sovereign/credit etc.) but the changing role of interest rate risk and duration in portfolios is a vital consideration. All of this points to a more diversified global fixed income portfolio, which includes EM debt and probably has somewhat shorter duration.

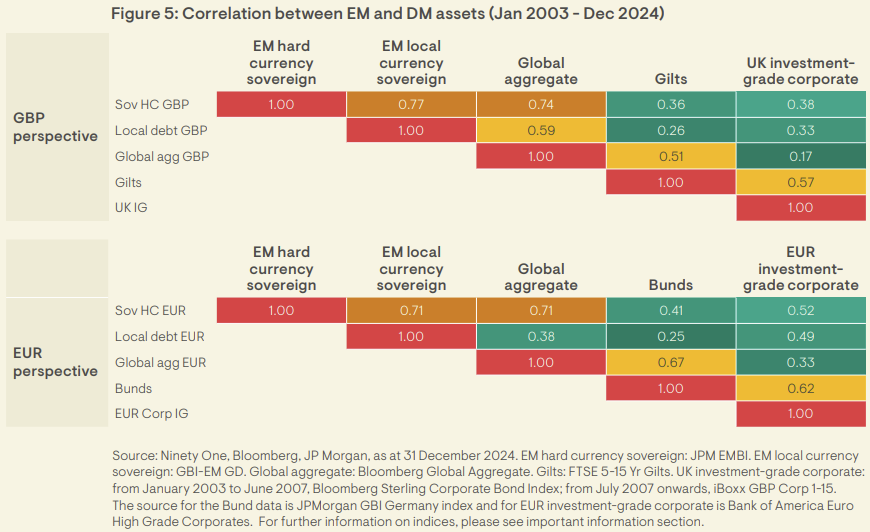

In this context, it is important to recognise the usefulness of EM debt as a portfolio diversifier, given the varied behaviour of individual asset classes across the cycle and the large dispersion across markets that sit within these. A key benefit to investing across all EM debt asset classes is that the performance of each sub-asset class is differentiated through the broader economic and monetary policy cycle.

EM debt – the great diversifier

The differentiated behaviour of local currency debt portfolios, especially for non-US dollar based investors, reflects the distinctive factors driving returns: differing interest rate regimes, divergent economic cycles and currency fluctuations.

All things being equal, the quality of the local currency debt opportunity set has improved in recent years through the addition of India and China, the removal of Russia from the index, and underlying improvements in the fundamentals of other countries, as noted earlier. Further, it is clear from analysing the behaviour within this opportunity set that not all countries sing to the same tune. In broad terms, there are three cohorts: high-quality Asia, Central and Eastern Europe, and then the more cyclical markets. The upshot is that in addition to its low correlation to other asset classes, there are significant diversifying forces within this asset class.

The hard currency debt market today is also highly diverse, spanning oil exporters and importers, regional manufacturing hubs and services-driven economies across the globe. The increased importance of frontier markets offers the opportunity for investors to take meaningful – and diversified – exposure to a broad range of underlying return drivers. Over time, the opportunity set has become more geographically diverse, and experienced an increase in longer-duration issuance from investment-grade issuers.

The different interplay of each of these EM debt asset classes also offers a diversification benefit that is not widely recognised.

In summary

Bond markets are in a new regime – one where old distinctions between EM and DM debt no longer hold and investors can no longer expect asset classes to behave as they have done historically. In short, we have seen the ‘EM-ification of DM’.

Asset allocation approaches need a reboot in a world where portfolio diversification has never been such a virtue, but the means to achieve this have changed. In this context, and supported by an enduring, positive shift in fundamentals, EM debt deserves a place at the global investor table.

Peter Kent is Co-Head of Emerging Market Fixed Income at Ninety One, an active, global investment manager. This article is provided for general information only should not be construed as advice.

General risks: The value of investments, and any income generated from them, can fall as well as rise. Costs and charges will reduce the current and future value of investments. Past performance does not predict future returns. Investment objectives may not necessarily be achieved; losses may be made. Target returns are hypothetical and do not represent actual performance. Actual returns may differ significantly. Environmental, social or governance related risk events or factors, if they occur, could cause a negative impact on the value of investments. Specific risks: Emerging market (inc. China): These markets carry a higher risk of financial loss than more developed markets as they may have less developed legal, political, economic or other systems.