One of the common reasons given by advisers against investing in fixed interest is that “you can’t grow your earnings”. After all, so the thinking goes, your interest is fixed. That must mean you can only earn a constant amount of income.

However, to borrow from Sportin’ Life in Porgy and Bess, it ain’t necessarily so. There is a simple way that investors can grow their fixed income earnings; in fact, many investors already do so without realising it. The strategy is to reinvest at least a portion of the interest payments. This grows the capital of the investment and enables compounding of interest.

Here’s an illustration. $100,000 invested in a ten year fixed income investment with a 4.5% interest rate will pay $4,500 a year if all the interest is taken as income. However, if the interest is reinvested then by the final year the income will have grown to $6,687 and the total value of the portfolio to $155,297. This assumes, for simplicity, that the same 4.5% interest rate can be earned throughout the period and, of course, ignores taxation. The year by year progression is shown in the following table:

| Year |

Interest earned |

End of year portfolio value |

|

1

|

4,500

|

104,500

|

|

2

|

4,702

|

109,203

|

|

3

|

4,914

|

114,117

|

|

4

|

5,135

|

119,252

|

|

5

|

5,366

|

124,618

|

|

6

|

5,608

|

130,226

|

|

7

|

5,860

|

136,086

|

|

8

|

6,124

|

142,210

|

|

9

|

6,400

|

148,610

|

|

10

|

6,687

|

155,297

|

By the final year of this investment, the initial outlay of $100,000 is earning $6,687 a year in interest even though the level of interest rates hasn’t gone up.

This is effectively what happens in many investments already. It happens in the fixed income component of superannuation funds, where all income is automatically reinvested, and also in term deposits where the reinvestment rate is the same as the initial yield.

Inflation risk

Of course, a lot of investors need to draw income from their portfolios and can’t simply reinvest all the interest. The trouble with doing this is that in ten years’ time the real value of the $4,500 interest payment (to use the above example again) has been eroded by inflation. If inflation was 2.5% over the ten years of this investment, the real value of the final year’s interest payment has declined to $3,515.

Can we get around this?

A variation on the full reinvestment strategy is to partially reinvest. This still enables some growth in earnings to take place, but also provides cash flow in the investor’s hand. If the inflation component of the interest rate is reinvested and only the real component is kept as income, then the income payment each year will rise in line with inflation and its purchasing power will be maintained.

Let’s say inflation is running at 2.5%. In this case, the investor in our example would reinvest $2,500 of the first interest payment and retain $2,000 (a ‘real’ rate of 2.0%). In year 2 the 4.5% rate would be earned on a portfolio of $102,500, delivering interest of $4,612. Of this, the inflation component for reinvestment is $2,562 and the investor keeps $2,050.

Continuing this process through the ten years of the investment results in the investor receiving an income payment of $2,498 in year 10, which will purchase the same amount of goods and services at that time as $2,000 could buy today.

The obvious question at this point is, what happens if inflation rises to more than 2.5%? A simplistic application of the strategy means that in those years the retained income is reduced. For example, if inflation in one year is 3.5% then the investor would only take an income payment of 1.0% of the portfolio in that year.

Alternatively, the investor might assume that the following year’s inflation will fall back again – as the RBA would likely tighten monetary policy to achieve that outcome – and continue to follow the 2.5/2.0 split. This is an imperfect response, but provided inflation does average 2.5% over time, it still delivers the outcome intended.

There is another more elegant alternative.

Inflation-linked bonds

In essence, inflation-linked bonds (ILB) automatically follow the strategy outlined above. A real yield is paid each year, with an inflation component reinvested. The nominal capital value of the investment increases in line with inflation and thus the income that is generated is also maintained in real terms.

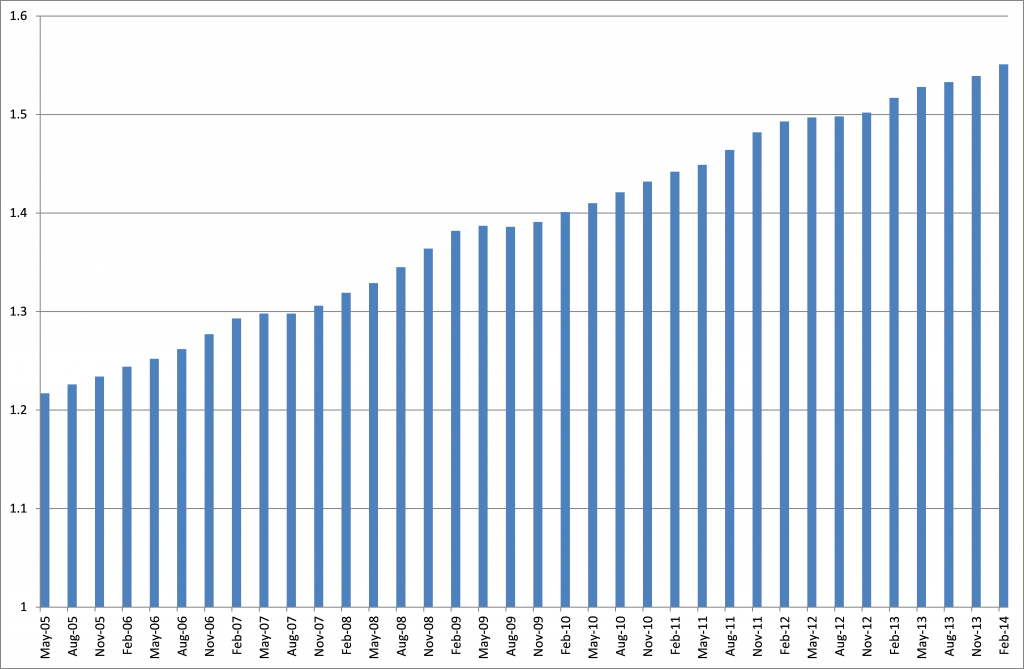

The following chart shows the actual history of the quarterly interest payments since 2005 of the Commonwealth Government’s ILB maturing in 2020. On the y-axis, 1.2 means $1.20 for every $100 of original face value purchased, or 1.2% of face value (same thing).

The steady increase in the interest payment over time means that by this year (2014) an investor who bought this security and held it through the period is now being paid 27.5% more income than they were nine years ago. Over the same period consumer prices, as measured by the CPI, have also increased by 27.5%.

Comparing the approaches

The key difference between nominal bonds and ILB, which makes ILB better at protecting investors against inflation, is that with ILB it is only the real yield component that is fixed.

In the example we’ve been using, this is the 2.0% component. The combination of the real and the inflation components isn’t fixed at 4.5%, as is the case with nominal bonds. Whatever the inflation rate, the capital value of the ILB will adjust and the investor is paid each year 2.0% of that amount.

The difference between the yield on a nominal bond and the real yield on an ILB of similar maturity is the break-even inflation rate. In our example, this is 2.5%. A steady inflation rate of 2.5% would produce identical investment outcomes from either holding an ILB or using the reinvestment strategy with nominal bonds.

ILB come out ahead over the longer term if inflation during the life of the security exceeds the break-even at purchase. For example, if inflation ended up being 3% a year instead of 2.5%, the ILB would end up growing by 5% a year instead of 4.5%.

This is especially useful when there are jumps in inflation due to policy changes. For example, if the GST rate were to be increased and the CPI to jump, the capital value of the ILB will adjust upwards and in turn so will the interest payments.

On the other hand, if inflation were to track at a lower average than the break-even rate, then the nominal bond approach achieves a superior outcome.

Concluding remarks

The point of this discussion is not to argue that investors should choose fixed income over any other asset class. For example, it says nothing about the relative attractiveness at any point in time of interest rates against dividend yields or property rental yields. Rather, the point is simply that investors need not shun including fixed interest in their portfolios due to a misunderstanding about the potential for earnings to grow at least in line with inflation. Fixed income is a good asset class to use for inflation risk management – not only inflation linked bonds, but nominal bonds also.

Warren Bird was Co-Head of Global Fixed Interest and Credit at Colonial First State Global Asset Management. His roles now include consulting, serving as an External Member of the GESB Board Investment Committee and writing on fixed interest.