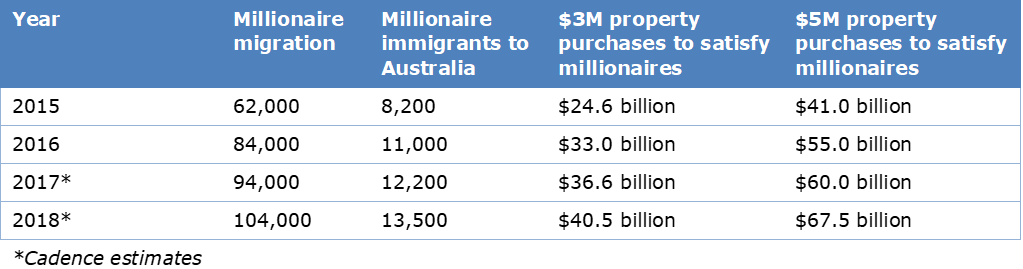

A 2017 report by market research firm New World Wealth concluded that a record 82,000 millionaires moved to a new country in 2016, up 26% from 62,000 in 2015. The estimate is that approximately 100,000 millionaires will move country each year by 2018. A millionaire in this report is defined as those having at least US$1 million of assets less liabilities excluding the family home.

The number one destination is Australia with 11,000 millionaires moving here, followed by the USA with 10,000 millionaire immigrants and Canada with 8,000. United Arab Emirates and New Zealand fill spots four and five.

Interestingly the number one destination millionaires are leaving is France with 12,000 millionaires fleeing the country in 2016. The New World Wealth Report estimates that China ranks second.

What does millionaire migration mean?

There are estimated to be 13.6 million millionaires in the world. The 100,000 that are changing country is not a big percentage but it is worth thinking about what the net inflow of millionaires can do to a country, particularly one with a relatively small economy.

My analysis is based purely on scenarios I have put together with data that cannot be easily verify (see Table 1 below). I have assumed that most millionaires with net investable assets of US$1 million would live in a significantly above-average home, maybe worth US$2 to US$3 million. I have also assumed that millionaires who move to a new country, on average, have more than US$1 million of net investable assets, as ‘wealthier’ millionaires would have a higher propensity to move than the millionaires who barely ‘scrape’ onto the list. Some of these immigrants could have US$2 million, US$5 million or US10 million of net investable assets and would consequently want even bigger and better houses than those with ‘only’ US$1 million of net investable assets.

Now let’s assume that of the 11,000 immigrant millionaires that come to Australia, 60% go to Sydney, 30% go to Melbourne and the remainder go elsewhere. In Sydney as an example, 6,600 immigrant millionaires are arriving every year wanting to purchase a property worth say A$3-4 million. Those with significantly more net investable assets probably want to spend A$5-8 million on houses and those with greater amounts of assets want to spend A$10 million plus on a house. These millionaires are looking to spend a minimum of $26 billion per year on 6,600 high-end houses in Sydney. And according to New World Wealth, millionaires are looking to spend this much every year as each new batch arrives. The prediction is also that this number is rising dramatically.

The problem becomes obvious. Sydney does not have enough expensive houses to accommodate all these new millionaires, and it looks to be getting worse. Of course, the result is lots of little ‘bubbles’ all around the world in places where millionaire immigrants decide they are going to live.

What does all this millionaire migration say about a country’s underlying economy? Clearly, the property sector and all ancillary services associated with property would be performing well. Of course, it does not necessarily follow that other parts of the economy benefit equally. You could even have extreme situations where those parts of the economy that benefit from millionaire inflow do well and other parts of the economy could go backwards.

Income inequality and the economy

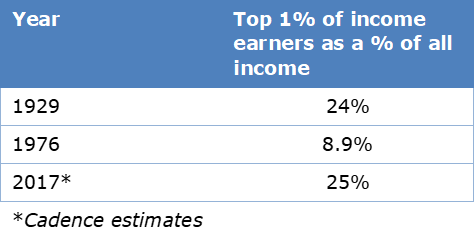

Another way to think about millionaires is as the 1 percenters or the 0.1 percenters (see table below). In 1929, the top 1% of pre-tax income earners accounted for roughly 24% of all pre-tax earnings. This fell to 8.9% in 1976 but is once again at record levels of around 25%. The top 1% of earners in the world account for around a quarter to a third of all earnings and consumption in the world. This small 1% group and the even smaller 0.1% group have a disproportionate and large effect on the world economy. This small group of people also has a disproportionate effect on particular areas within our economy which may not translate to the greater economy.

The millionaire immigrant and the 1 percenters are creating bubbles around the world, especially in property in cities like Sydney, Vancouver, Auckland, Hong Kong and London. When we see such large demand and supply imbalances, we should consider the underlying factors creating these distortions. In small economies, these distortions are not necessarily a sign of the strong performance of the underlying economy.

Rather than conclude with a note of caution, our immediate problem is that we need to come up with a solution to satisfy this year’s and next year’s millionaire immigrant requirements!

Karl Siegling is Portfolio Manager at Cadence Capital.