You’ve got a lump sum of cash, and you want to start investing in the stock market. You might consider ploughing it all in today. But then you worry: what if the share market then slumps?

Fortunately, there is a wealth of data available that can help investors make better-informed decisions.

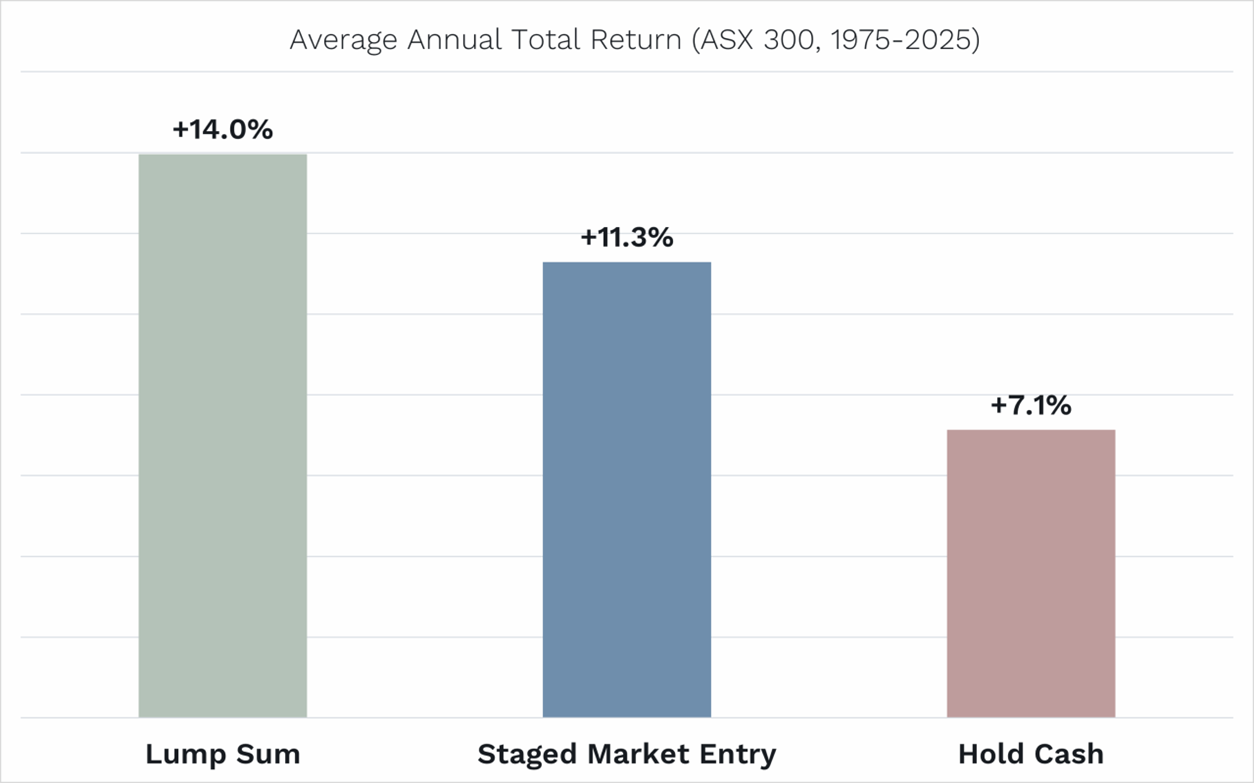

Below, for the last 50 years of Australian share market data (ASX 300 index), you can see the average 12-month results for:

- ‘Lump sum’ investing (investing all at once).

- ‘Staged market entry’ (four equal investments at the start of each quarter over 12 months).

Source: Bloomberg. ASX 300 total return used for Lump Sum option. ASX 300 total return and Bloomberg Ausbond Bank Bill Index returns used for calculating Staged Market Entry return. Bloomberg Ausbond Bank Bill Index return used for Cash return.

On average, lump sum investing wins.

This makes sense because share markets tend to rise over a year. Delaying your investment through staged entry is, therefore, on average, going to hurt you.

And, of course, just sitting in cash earning interest has provided the worst result – though investors today would love to get a 7.1% return from their cash investment! [1]

Lump sum risk

BUT, that is not the end of the story.

The world does not live in averages.

As famed investor Howard Marks said: “Never forget the six-foot-tall man who drowned crossing the river that was five feet deep on average”.

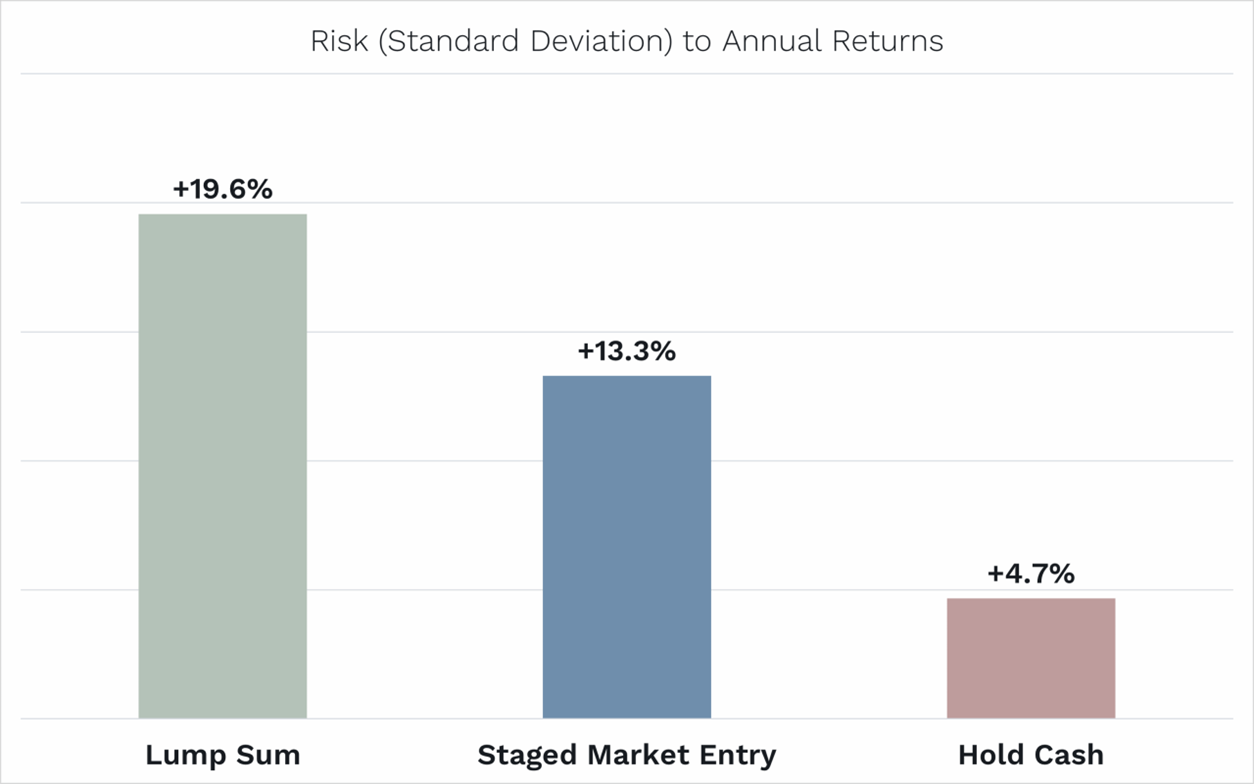

If we look at the ‘risk’ to those average annual returns we saw above – or the spread of outcomes around those averages – we see that lump sum investing was the riskiest.

Source: Bloomberg. Data from 1975 to 2025.

You don’t have to be a brainiac to understand why.

The share market return is more volatile than keeping all, or some, of your money earning interest from a cash investment. So going in all at once means you could do either a lot better than the 14% average … or a lot worse.

Naturally, by potentially staging their investment, it’s the ‘lot worse’ outcome investors are thinking of protecting against.

Like an insurance policy

So next up is the really insightful data to help you make your decision.

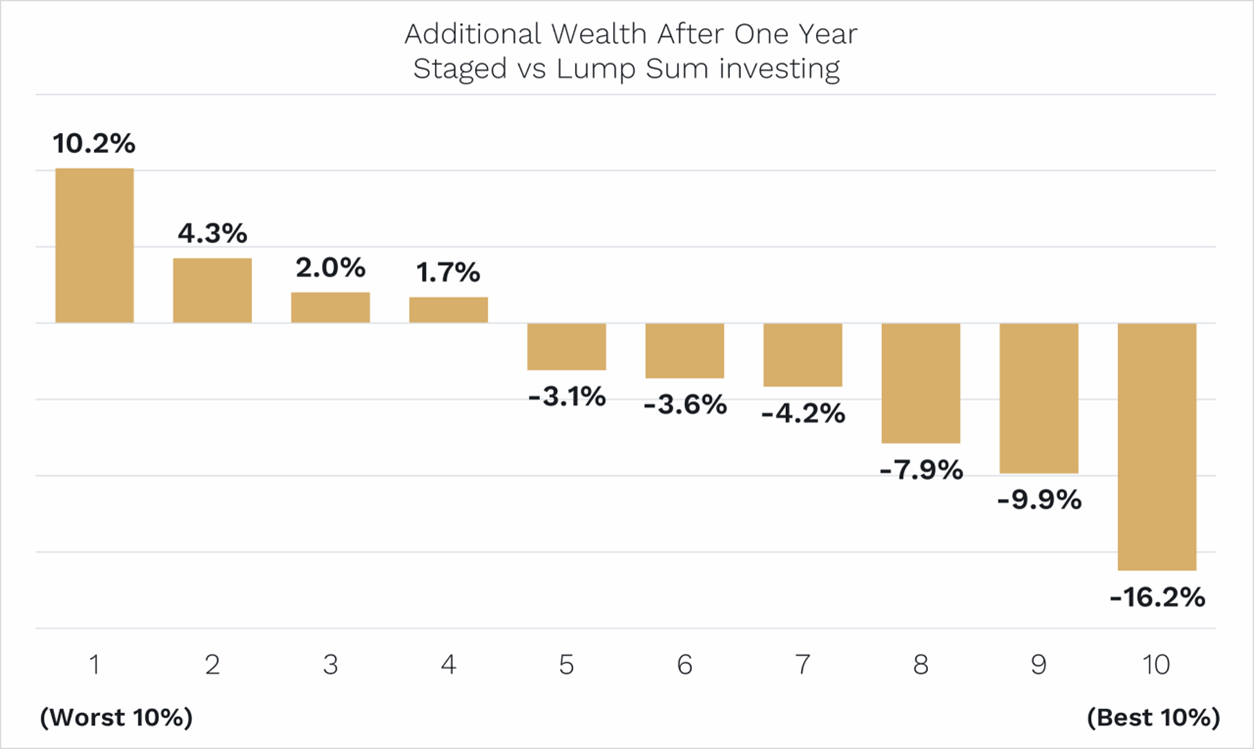

We have chopped share market returns over a year up into 10 deciles – or in other words, 10 equal baskets from the worst 10% of annual share market returns to the best 10%.

We have then looked at how much more, on average, you’d be better off from staging market entry compared to lump sum investing.

Source: Bloomberg. Data from 1975 to 2025.

What you can see is that:

- Staging makes you better off if share market returns are in the lowest return four deciles, or the worst 40% of returns.

- However, more often, staging makes you worse off because it underperforms in the best six deciles or best 60% of returns.

- There is also a ‘negative skew’ to staging. That is, staging makes you worse off to a greater extent in the best returning share market environments than it makes you better off in the worst returning share markets (i.e. -16.2% versus +10.2%).

The best way to think of staging market entry is like an insurance policy on your house burning down. Most of the time, you won’t need the policy, and it’s costing you money.

However, if your house burns down, or in this case, if you have unfortunate market timing and the share market falls after you’ve just started investing, then staging will have saved you money.

Why not just be a better market timer and only invest in a lump sum when you know the share market is going to go up over the next 12 months?

Sadly, that’s not possible.

Things like an expensive share market, or one that has gone up a lot over the past year, have virtually zero predictive power of what the share market is going to do over the next year.

And the longer you wait in cash for a ‘perfect’ share market opportunity, the likely longer you will have been sitting on the sidelines watching a rising share market go by.

A better-informed decision

So, as we see it, just like whether to purchase insurance for a house that might burn down, each individual needs to make up their own mind as to whether the insurance from staging your market entry – which will likely cost you money on average – is worth it for the peace of mind that it will have saved you money if share market returns turn out poor over the next year.

In our experience, for big, meaningful investments, many people choose to stage.

Ultimately, the choice is yours.

But hopefully, you are a little more informed now to make your decision.

[1] This seemingly high 7.1% average 12-month cash return is so high in large part due to the high interest rate/inflation years in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Andrew Mitchell is Founder, Director and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ophir Asset Management, a sponsor of Firstlinks. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.

Read more articles and papers from Ophir here.