In brief

- Market booms often lure investors into cyclical businesses, but history shows these cycles can be short-lived and expose investors to severe drawdowns and difficult recovery math.

- Compounders tend to deliver steadier, more durable profit growth across full cycles, making them better suited for long-term investors.

- Selectivity is especially important given the unique, negative economies of scale of some AI businesses.

In the heat of a market boom, the siren song of cyclical businesses can be almost impossible for investors to ignore. Whether it was the credit-fueled surge of the mid-2000s, the post-lockdown commodity spike, or the current frenzy surrounding hardware-heavy technology cycles, the narrative is always the same: this time, the scale is different.

History is filled with 'must-own' stories that were cycles in disguise. In the 1720s, it was the South Sea Company, where investors rushed to own a global trade monopoly, only to see their capital evaporate when profits failed to meet expectations. A century later, railways were going to change the world — and they did. However, excess competition and overcapacity wiped out the investors who funded them.

The lesson history teaches us is that cycle booms are finite. While the 'up cycle' provides the dopamine hit of outperformance, it’s the full cycle that determines total return on capital.

This informs why we at MFS structurally lean away from 'cyclicals' and towards 'compounders'. To put this into greater context as we head into 2026 and navigate the heat of a technology “up cycle,” we offer a hypothetical look at the hard math of losses during a full cycle.

A tale of two P&Ls

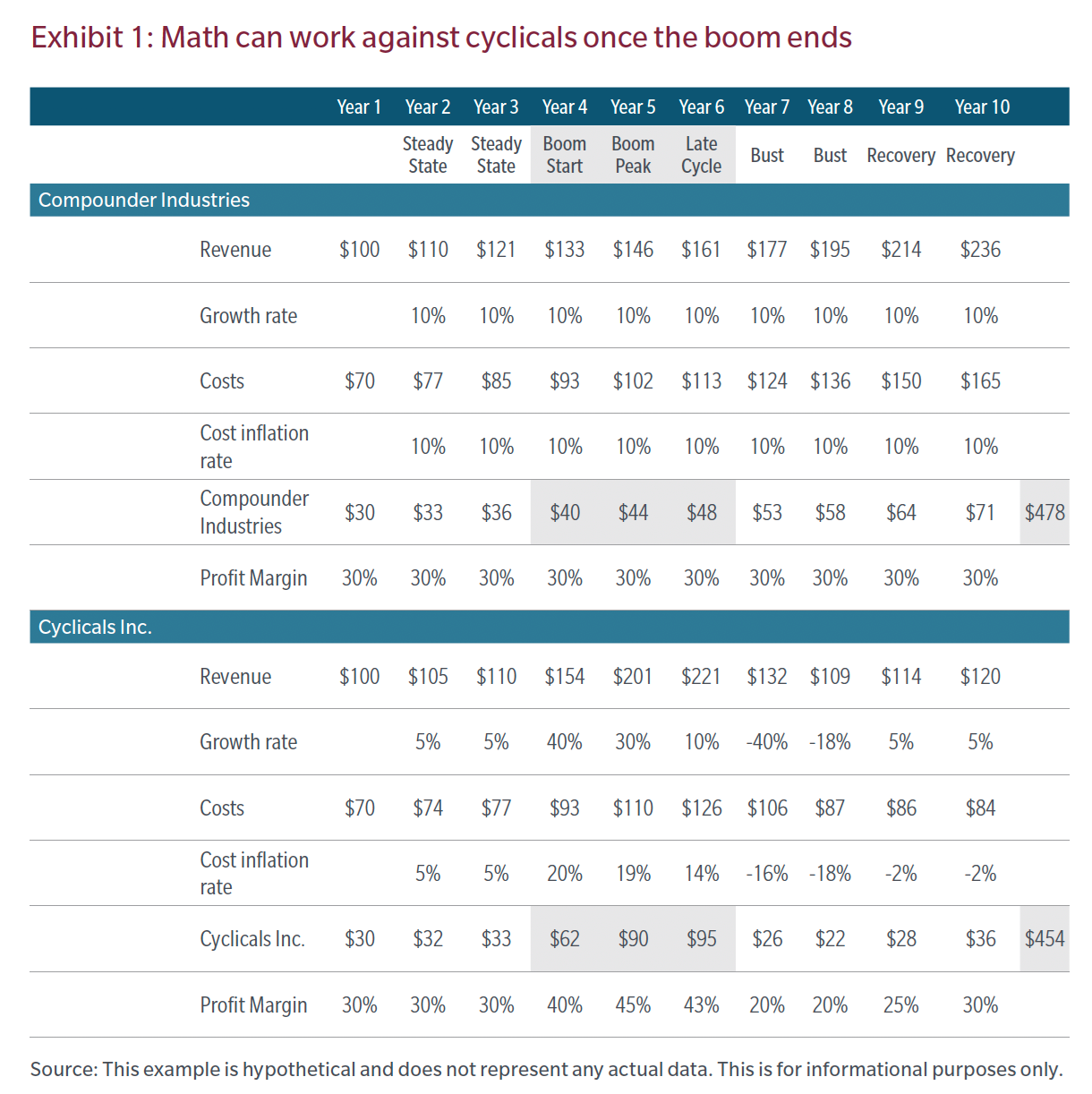

Consider a hypothetical 10-year window involving two businesses: Compounder Industries and Cyclicals Incorporated.

As shown in Exhibit 1, both start at the same place: $100 million in revenue and a healthy 30% profit margin. For the first few years, Compounder Industries raises revenue and costs at a steady 10% clip, maintaining its margin. It follows the mantra of “build it once, sell it a bunch,” utilizing high operating leverage and differentiated products to generate consistent profits.

Then comes the 'boom'. A new technology or economic shift emerges, directly benefiting Cyclicals Inc. Revenues explode by 40%. Investors, captivated by the sudden margin expansion to 45%, rotate out of shares of Compounder Industries and into Cyclicals Inc. For the next three years, Cyclicals Inc.’s margins and profits materially outpace the market.

The asymmetry of the bust

By Year 7, the cycle peaks as new competition saturates the market with supply. Cyclical Inc.’s sales fall by 40%. Despite aggressive cost-cutting and layoffs, profit margins are halved.

Though this scenario is hypothetical, the assumptions are rooted in history and designed to expose the mathematical trap that investors often overlook: to recover from a 40% drop in revenue and return to its Year-6 peak, Cyclicals Inc. doesn’t just need a 'good' year — it needs to grow by 67% in a single year just to get back to even. That is an enormous hurdle that Compounder Industries never has to face.

The full-cycle experience

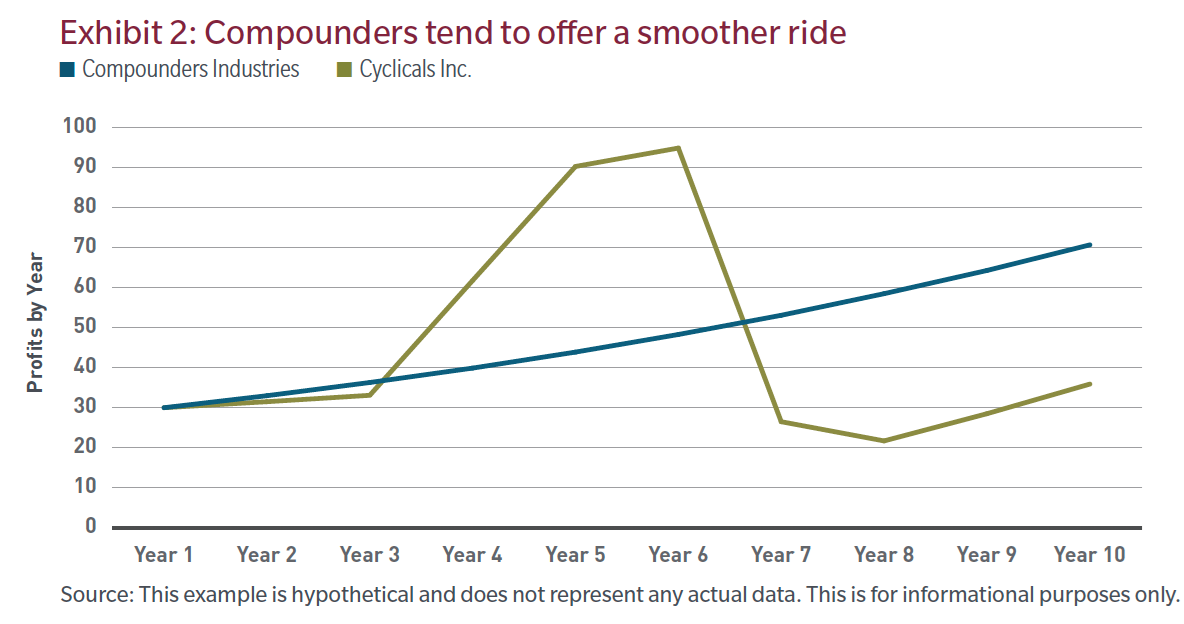

So, while both companies reach approximately the same total profits of just over $450 billion, their pathways are different. Compounder Industries’ annual returns were almost double and with less volatility, as illustrated below.

Conclusion

In recent years, we’ve seen a massive rotation into companies tethered to product cycles — specifically technology hardware driven by AI. Some of today’s AI models operate with negative economies of scale: every query triggers expensive compute costs that exceed revenue. This is the antithesis of the Internet 2.0 era, in which network effects created monopolies with historic profit growth. We believe these changed fundamentals warrant selective, rather than broad-based, exposure to today’s technology businesses.

'Quality' is a term used so often in this industry that it has lost its teeth. At its core, quality isn’t about a label; it’s about the ability to avoid the 'math of the bust'.

We favor companies that we think can compound earnings through differentiated products and scalable structures. While the compounder might be a laggard during a boom, like today, they are often the ones delivering better financial outcomes for the patient, long-term investor who possesses a deep, fundamental framework.

Robert M. Almeida is a Global Investment Strategist and Portfolio Manager at MFS Investment Management. This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to invest in any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It has been prepared without taking into account any personal objectives, financial situation or needs of any specific person. Comments, opinions and analysis are rendered as of the date given and may change without notice due to market conditions and other factors. This article is issued in Australia by MFS International Australia Pty Ltd (ABN 68 607 579 537, AFSL 485343), a sponsor of Firstlinks.

For more articles and papers from MFS, please click here.

Unless otherwise indicated, logos and product and service names are trademarks of MFS® and its affiliates and may be registered in certain countries.