The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

We’re bombarded with news about the ‘demographic time bomb’ that’s coming. Of rising dependency ratios (ie. a fall in total employment rates) and declining economic growth rates. It’s not only in Australia but across most developed markets.

However, new research from Goldman Sachs and IMF suggests that the problems caused by ageing populations may not be intractable. In fact, there are more positives than negatives when it comes to ageing.

Yes, the world’s population is ageing

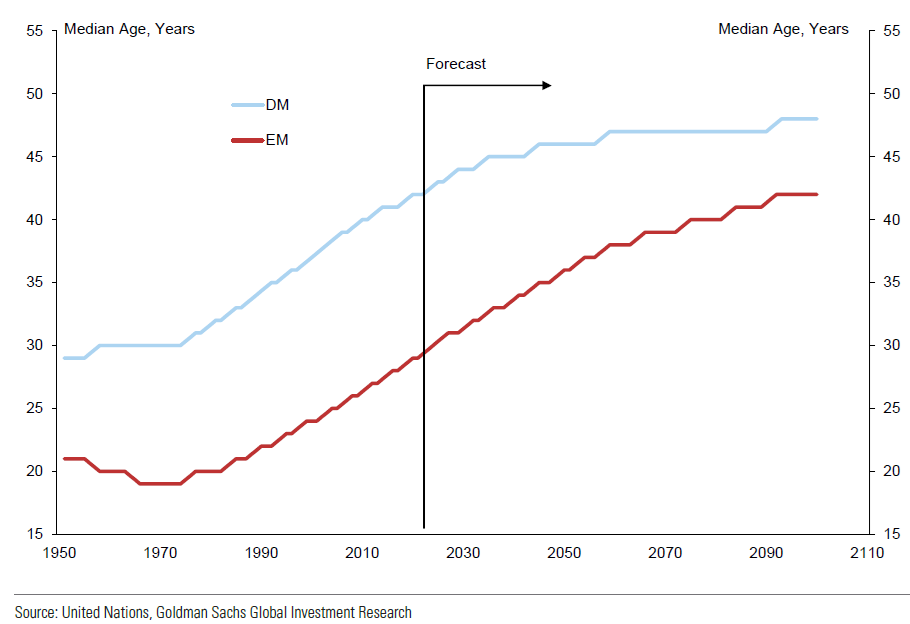

There’s no denying that the world is getting older. Over the past 50 years, the median age in developed market economies has increased from 30 to 43 years, while in emerging markets it’s risen from 19 to 30.

The United Nations predicts that over the next 50 years the median age will reach 47 years in developed markets and 40 in emerging markets.

There are two key factors behind the world getting older.

First is increased longevity. Since 1975, average global life expectancy has risen from 62 to 75 years. In developed countries, it’s increased from 72 to 82 years while in emerging countries it’s jumped from 58 to 73 years.

It hasn’t all been linear or universal. For instance, you might be surprised to know that US life expectancy has dropped over the past decade.

Yet, generally, longevity has improved. Today, Hong Kong leads the world with a life expectancy of 86 years. Australia isn’t far behind, at 83 years.

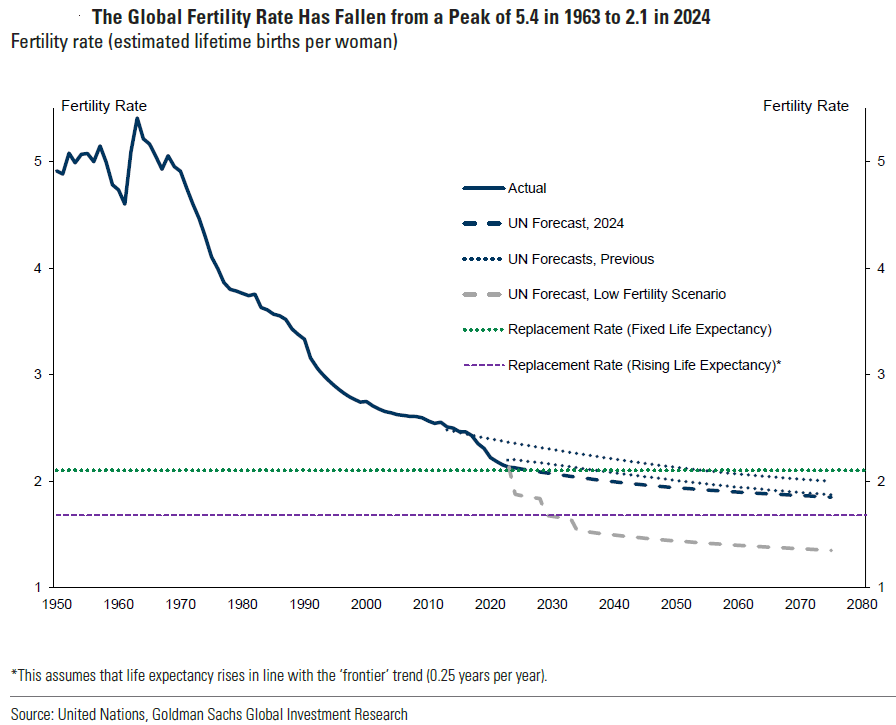

The second factor behind ageing populations is declining fertility. The global fertility rate – the estimated number of births a woman will have in her lifetime based on current birth rates – peaked at 5.4 in 1963 and stands at 2.1 today. Australia’s fertility rate is 1.63, which is better than most of the developed world.

A common perception is that most of the fertility decline has happened in developed markets, but that’s not the case. The emerging market fertility rate has plunged from 4.6 to 2.2 since 1975, while the developed market rate has fallen from 1.9 to 1.5.

The global fertility rate is in line with the estimated replacement fertility rate of 2.1. However, most developed countries are trending well below this replacement rate.

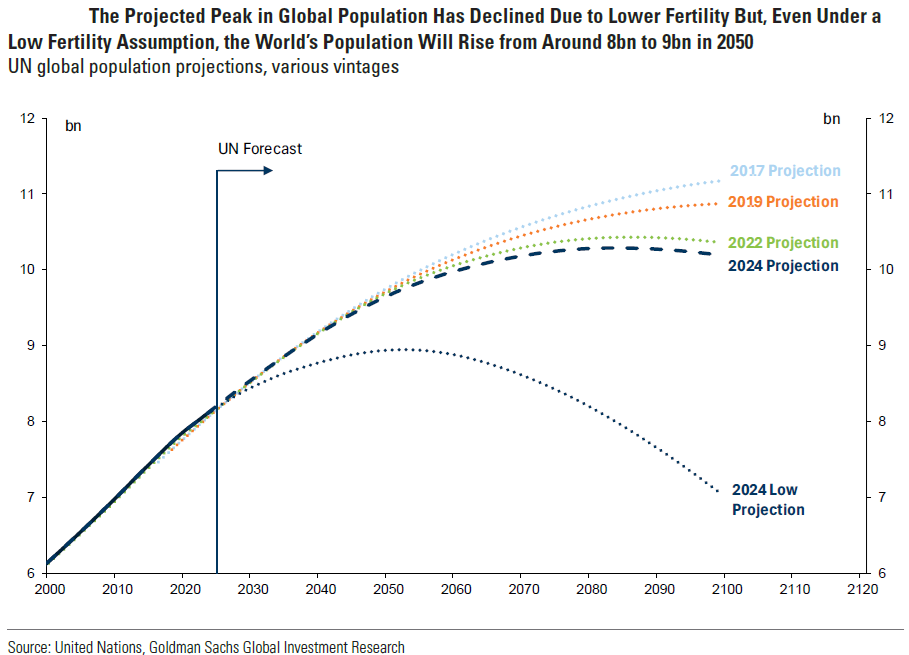

Even on pessimistic estimates for global fertility rates, though, the world’s population is still expected to grow for another 25 years, peaking at around 9 billion.

A demographic time bomb?

There’s little doubt that ageing populations are impacting economic growth and will continue to do so. After all, GDP is a product of the number of employed people and the amount of economic output that each produces. If population growth falls, GDP growth is likely to follow suit.

Global population growth peaked at 2% per year in 1975 and is currently running at 1% per year. That’s projected to drop to 0% over the next 50 years.

Yet it should be noted that while this will affect headline GDP growth rates, it won’t impact per capita or per person GDP rates.

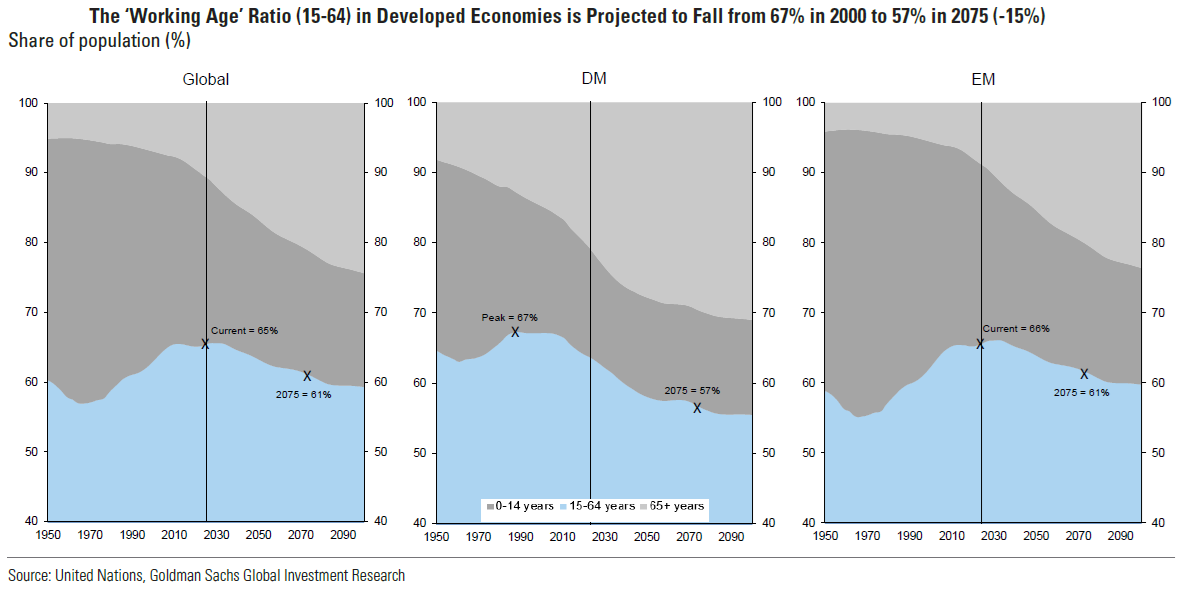

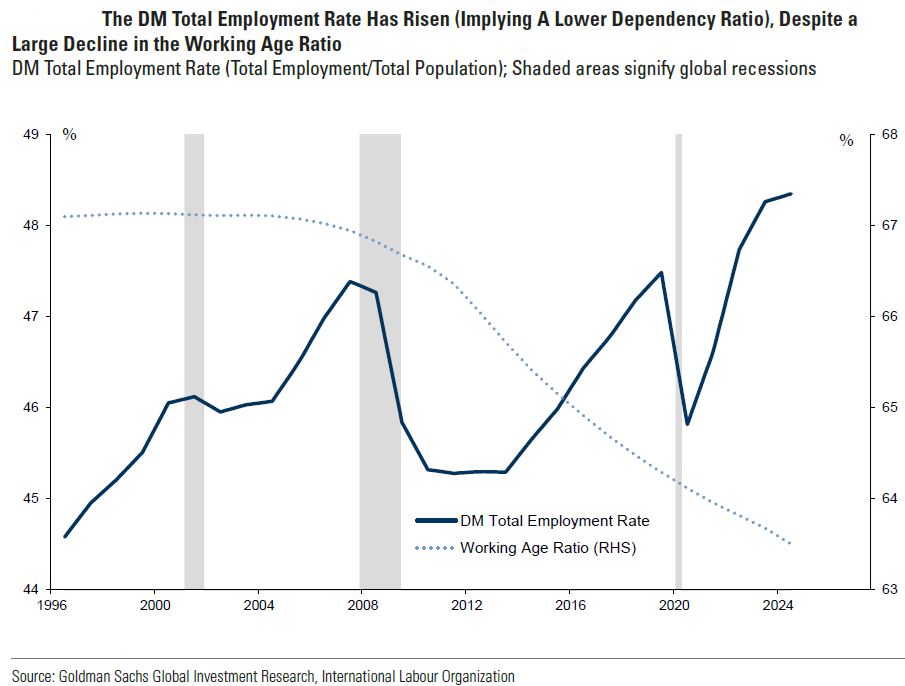

The bigger worry is the ageing population will lead to a decline in the working-age ratio – the proportion of people aged 15 to 64. A fall in that ratio will hit both employment rates and GDP per person.

The working-age ratio has already significantly decreased in developed countries. From 67% in 1985, it’s fallen to 63%, and is estimated to decline further to 57% over the next 50 years.

Emerging markets are faring better. Their working-age ratio is close to a projected peak of 66% and is predicted to decrease to 61% by 2075.

The problems aren’t insurmountable

These headwinds from ageing are well documented but are they insurmountable? Goldman Sachs thinks not. It says the challenges can be met by people extending their effective working lives.

I know what you’re thinking – great, Goldman wants us to work longer. That’s right, but the point is that we’re already living longer and that should continue for some time yet, so extending work in line with increased longevity makes some sense.

Goldman estimates that to offset the working-age ratio decline in developed markets over the next 50 years, it would require us to extend working lives by 7.5 years.

That’s a lot! However, it’s a little misleading. Working age ratios are calculated using ages 15-64. The reality is that we enter the workforce later than age 15 on average. Therefore, the 7.5 years’ work extension estimated by Goldmans is likely to be less than five years.

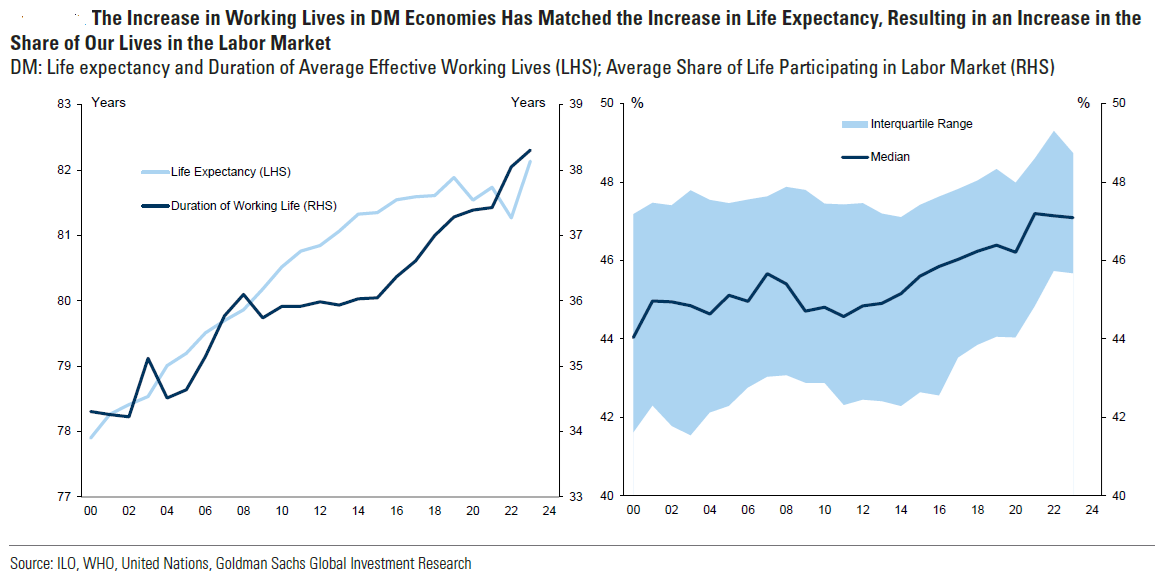

That might still sound a lot. Keep in mind though that the trend towards extending working lives is already underway. Since 2000, the average working life in developed markets has increased by four years.

You might think that this trend has happened due to changes to pension age laws. However, there have only been minor changes, which suggests that we’re working longer in line with our increased longevity.

70 is the new 53

Healthier ageing has helped extend working lives. In a comprehensive study, the IMF has found that “on average, a person who was 70 in 2022 had the same cognitive ability as a 53-year old in 2000, while the physical frailty of a 70-year-old corresponded to that of a 56-year-old in 2000.”

The common assumption is that increased life expectancy will extend the amount of our lives that we spend in ‘old age’. Yet we’re much healthier in older age these days and that’s allowing us to work longer.

It’s showing up in the labor force data too. Goldman says that the “move towards extending working lives has more than offset the effect of population aging on DM [Developed Market] employment, with the result that employment as a share of total population have also risen materially since 2000, despite the significant decline in the DM working-age ratio over this period.”

All told, we’re handling the transition towards ageing populations quite well and that’s a good news story.

****

In my article this week, I suggest that the $3m super tax represents a broader revolt against the wealth of the Baby Boomer generation. Against the extent of their wealth, how they got it, and how those in power aided and abetted it - seemingly to the detriment of younger generations.

On the super tax, Professor Kevin Davis thinks that the proposal to include unrealised capital gains may lead to an effective cap on balances of $3 million. However, he proposes a simpler method to prevent excessive super balances.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

Ashley Owen looks in depth at the US market and with a price-to-earnings ratio of 28x and earnings forecasts of 15% growth over the next two years, he says a lot needs to go right for the market to continue its march higher.

A recent court case involving the Australian Tax Office could have a significant impact on the tax payable by beneficiaries of family trusts. Peter Bardos says that if the ATO has previously demanded extra payments on unpaid present entitlements in your family group, you should watch this space closely.

Subdividing can offer a lucrative first step into property development. Yet Danielle Hart and Daniel Walachowski say it comes with legal, planning and unexpected tax considerations that should be understood to avoid surprises.

This year has had its share of volatility in markets. Capital Group's Jorden Brown offers 5 tips to cope with the ups and downs, and ensure you remain on the right track.

There'a a lot of fear about China's rise to power. That it will be aggressive when it comes to Taiwan and projecting its power outwards. But Michael McAlary has doubts about that common perception.

Two extra articles from Morningstar this weekend. Angus Hewitt explains a big hike in his Qantas valuation, while Simonelle Mody highlights three ASX shares with exposure to data centres.

Lastly in this week's whitepaper, First Sentier explores an approach to integrating ESG considerations that can lead to better financial outcomes.

****

Weekend market update

In the US on Friday, risk aversion reigned following Israel’s overnight attack on Iran, with WTI crude oil vaulting towards US$74 per barrel, up 8%, while the S&P 500 retreated 1.1%, finishing near session lows. Gold jumped nearly 2% to US$3,433 per ounce, bitcoin retreated to US$105,300 and the VIX advanced three points to 21. Notably, Uncle Sam’s obligations proved no port in the storm, as 2- and 30-year Treasury yields each rose six basis points to 3.96% and 4.9%, respectively.

Australia's share market lost much of the week's gains on Friday, after Israel's attack on Iran proved a brutal reality check for risk sentiment. The S&P/ASX200 fell 0.21% to 8,547.4 as the broader All Ordinaries gave up .29% to 8,770.6.

Wednesday's dual-record intraday peak and best-ever close for the top-200 became a distant memory as Israeli air strikes on Iranian military targets and nuclear facilities prompted retaliatory drone attacks.

Eight of 11 local sectors lost ground on Friday, while energy and utilities stocks surged after oil prices spiked to four-month highs in the wake of the attacks.

Energy stocks and utilities both surged more than 4%, and the defensive consumer discretionary sector was the only other division in the green, up 0.25%.

The spike in crude prices was good news for Woodside investors, as the oil and gas giant rallied more than 7% to $25.21, the top-200's best performer.

Financial stocks, which account for roughly half of the top-200's value, fell 0.4% as three of the big four banks - excepting a flat Westpac - grinded lower. The sector was roughly flat for the week.

Materials stocks fell 0.2% as rallying gold miners helped soften a sell-off in large cap miners BHP (-2.6%) and Rio Tinto (-1.1%), tracking with an uplift in gold and continued weakness in iron ore prices.

Australia's tech sector took the biggest hit on Friday, down 1.2% as investors fled to safety.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

Global shares had a messy week pushed around by tariff news in the US, better than expected US inflation data and Israel’s attack on Iran’s nuclear capabilities later in the week. Prior to Israel’s attack the US S&P 500 was up slightly, but it fell 1.1% after the attacks and Iran’s retaliation leaving it down 0.4% for the week. Eurozone shares also fell 2.2% for the week with Chinese shares down 0.3%, but Japanese shares rose 0.2%. Despite falling on Friday after Israel’s attack, Australian shares bucked the global trend and rose 0.4% for the week after having hit a record high mid-week with the gains led by energy, utility, property and consumer stocks. Bond yields surprisingly rose in the US and Europe in response to the Israel/Iran strikes possibly on inflation fears, but they fell over the week including in Australia and Japan. Oil prices surged 13% for the week on fears of supply disruptions in response to the Israel/Iran conflict and gold rose with safe haven buying but copper and iron ore prices fell. Bitcoin rose slightly for the week, although it fell from a high above $US110,000 again as shares pulled back. The Australian dollar fell in response to the latest Israel/Iran flare up but was little changed for the week with the US dollar falling.

Geopolitical risk in the Middle East is up again with Israel launching attacks against Iran’s nuclear program, signalling more to come and Iran firing missiles and drones back at Israel. Oil prices were already rising this month on signs of increasing risks and spiked another 7% after the attacks – with the rise so far this month threatening a flow on of around 12 cents a litre for Australian petrol prices if sustained at these levels (although this may be lost in the discounting cycle which typically ranges more than 30 cents a litre in most cities). What happens in the very near term will depend on how Iran retaliates. It has already fired drones and missiles at Israel, but the main risk would be if it attacks US bases in the region (which is possible but likely to be limited) and neighbouring oil producers (which is unlikely) or if it disrupts/blocks the Strait of Hormuz through which roughly 20% of global oil consumption and 25% of global LNG trade flows daily (which is possible). It is the latter which poses the biggest upside risk to oil prices, but the good news so far is that Israel has not attacked Iran’s energy infrastructure which may dissuade it from doing anything like disrupting the Strait of Hormuz.

In any case central banks including the RBA will likely look through any near-term boost to inflation from higher petrol prices. And don’t forget that oil prices have just gone back to levels seen over much of the last year. Beyond the near term, the key will be if Iran returns to the nuclear talks with the US. It’s possible that Israel by its attacks (and the US behind it) is trying to force Iran to do this by sending a warning that if it doesn’t comply it faces an even worse attack from the US. In fact, Israel’s National Security Adviser has said that the intention was to “create the conditions for a long-term deal…that will completely thwart the nuclear program” and Trump has urged Iran to make a deal “before it is too late.” So maximum pressure is back on. But for shares it likely means a renewed period of uncertainty given the risk of even higher oil prices in the near term. Interestingly, while gold received its usual safe haven boost from the Israeli strike, the US dollar rose only slightly and US bond yields actually rose, providing another indication of the reduced safe haven status of US assets.

Curated by James Gruber, Joseph Taylor, and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

Monthly Bond and Hybrid updates from ASX

Listed Investment Company (LIC) Indicative NTA Report from Bell Potter

LIC (LMI) Monthly Review from Independent Investment Research

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website