The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

“There are many things money can buy, but the most valuable of all is freedom. Freedom to do what you want and to work for whom you respect.”

- J. L. Collins, The Simple Path to Wealth

Many of us dream of having enough money to do whatever we want. If we want to lie on a beach for months on end, we can do that. If we want to travel the world, we can do that. If we want to keep working part-time, and pursue more leisure activities, we can do that.

In many eyes, this is what wealth can bring: freedom.

Is it true, though? It certainly has a ring of truth. If you only just get by on a meagre income, it will feel like you don’t have much freedom. You must have a job, even if you hate it. You must take orders from the boss. You may have to take two jobs and limit free time, just to make ends meet.

More wealth can give you greater options and freedom. The freedom to pick better jobs and bosses. The freedom to possibly not work at all. And more broadly, the freedom to deal with who you want and when you want to.

But is it freedom that we’re really after? I’m not so sure. Often when we talk about freedom, we really mean time. We want more money to free up our time.

We’ve all heard the saying that “time equals money;” perhaps it should be “money equals time.”

Is time what we’re really after? I’m not so sure about this either. If you look carefully at what drives our desire for more time, underlying it is the quest for greater happiness. Often, we assume more time will lead to more happiness. If we have the money, we can have the time to pursue what we desire most and that will make us happy.

That may be right, though I know plenty of retirees who have all the time in the world, and aren’t happy. Time doesn’t automatically lead to greater happiness.

Numerous academic studies bear this out. The consensus of these studies is that money increases happiness to a point, and then it plateaus. And that point isn’t that high, at around US$75,000 (A$114,000) in income a year.

This makes some sense. Once we have our basic needs covered – the bottom of Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs – then we’re generally pretty satisfied.

And academics have found that the characteristics we possess when having less money persist with greater wealth. In other words, if you’re a twat when poor, you’ll still be a twat when rich. If you’re a friendly person when less well off, you’ll remain that way with more money.

So, underlying the concepts of freedom and time is happiness.

That leads to the obvious question: if money can’t make us happy, what can?

Through the centuries, a lot of people have searched for an answer to this.

These days, ‘self-improvement’ is all the rage. If we have a slim body, we’ll be happy. If we have a great job, that will make us happy. Or, if we get in touch with our inner feelings, that will lead us to everlasting happiness. You’ll see these things lining the shelves at your local bookstore under the heading of ‘self-improvement.’

Despite all this ‘self-improvement,’ though, it doesn’t seem like happiness is on the rise, and that’s shown in many surveys both here and overseas.

It’s easy to see why self-improvement may not be the way to go. After all, self-improvement is focused on your own needs – on the self. And typically focusing on your own needs doesn’t increase satisfaction in life.

In my experience, it’s the opposite. The happiest and wisest people that I know are more often focused on the needs of others. Helping and caring for others, with no expectations of anything in return.

That reminds me of a happiness equation I once read:

Happiness = reality - expectations.

People who help others and expect little in return can’t help but have reality exceeding their expectations.

I’ll end with an anecdote I came across a few months ago.

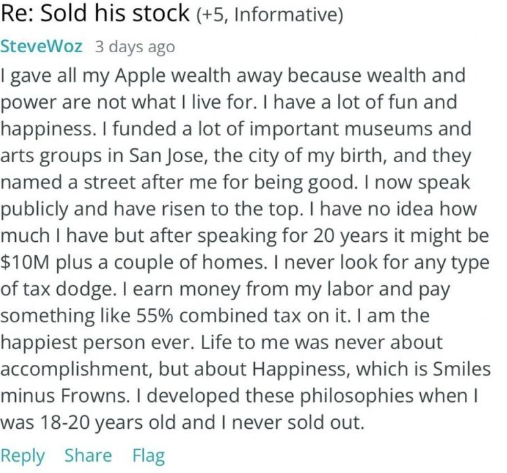

Steve Wozniak was one of the founders of Apple, alongside Steve Jobs. He left Apple in 1985 to pursue other things and sold all his stock around then too.

On the Reddit website in August, one commenter ridiculed Wozniak for selling the stake in Apple, which would be worth US$300 billion now, give or take: "Smart man. Great engineer. Bad decision."

Then, Wozniak popped up to reply to the thread:

Smiles minus frowns…

Wealth bought Wozniak freedom and time, though happiness came from giving to others, and ultimately creating more smiles over frowns.

A fine motto to live by.

****

In my article this week, I interview Mark Freeman, CEO at Australian Foundation Investment Company, the largest listed investment company in Australia. Mark discusses how speculative ASX stocks have crushed blue chips this year, companies he likes now, and why he’s confident AFIC’s NTA discount will reverse.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

Jamie Wickham is back with an article on solving the great Australian stock market conundrum - how to invest in an index over-reliant on old-world banks and miners. He has some ideas on building durable Australian equities portfolios that can outperform going forward.

Schroder's Martin Conlon has a different take on the issue. He says the ASX is divided between the haves and have-nots, or growth and momentum stocks versus the rest. He thinks the best future returns will come to those willing to veer away from the crowd to find opportunity.

Harry Chemay updates us on warnings from APRA and ASIC to super funds about lifting their retirement focus. It's becoming an urgent need with a forecast 2.5 million Australians commencing their journeys toward retirement in the coming decade, joining over 4 million retirees already there.

Global fund manager, GQG, caused quite a stir when it came out with its original "Dotcom on Steroids" report in September, positing that today's AI bubble has all the hallmarks of the 90s tech bubble. Today, it's back with part 2, focusing on OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, whose business model GQG says isn't sustainable. If that's right, it could have major implications for the Magnificent Seven stocks, as well as broader markets and economies.

Yarra's Phil Strano offers an alternative view on the parallels between today's AI bubble and that of tech in the 90s. He explores how ‘hyperscalers’ including Google, Meta and Microsoft are fuelling an unprecedented surge in equity and debt issuance to bankroll massive AI-driven capital expenditure. It's similar to what European telcos did during the tech bubble, and the outcome then wasn't pretty.

Leveraged ETFs seek to deliver some multiple of an underlying index or reference asset’s return over a day. Yet, Jeffery Ptak finds that they aren’t even delivering the target return on an average day as they’re meant to do. It's a revelatory piece on the potential pitfalls of buying leveraged stock ETFs.

Two extra articles from Morningstar this weekend. Nathan Zaia looks at whether AUB is an opportunity after its shares plunged on a failed takeover bid, while Yingqi Tan explores whether the data centre party is over from Goodman Group.

Lastly, in this week's whitepaper, Fidelity looks at the longevity revolution and how investors can prepare for that new reality.

***

Weekend market update

In the US, Treasurys remained under pressure with 2- and 30-year yields rising four and three basis points, respectively to 3.56% and 4.79%, while stock notched another modest gain on the S&P 500, wrapping up a 1% advance for the week to leave the broad index just below its high-water mark. WTI crude edged above US$60 a barrel, gold ebbed to US$4,201 per ounce, bitcoin declined to US$89,400 and the VIX settled at 15.5, its lowest close since early October.

From AAP:

Australia's share market has scraped to a second straight week of gains, as strong commodity prices counterbalanced weakness in most sectors.

The S&P/ASX200 edged 16.2 points higher on Friday, up 0.19%, to 8,634.6, as the broader All Ordinaries crept up 19.4 points, or 0.22%, to 8,926.1. The top-200 ultimately rose 0.24% over the five sessions.

Only four sectors gained over the week with raw materials and energy stronger on the back of underlying commodity prices, while financials and utilities stocks eked modest gains.

Volatility brought trading to a glacial pace for most of the five sessions, with investors wary ahead of the upcoming Reserve Bank meeting.

The big four banks all closed higher on Friday, helping the sector clock a 0.3% improvement for the week, as CBA appeared to find a price floor of around $150 after its recent pullback. Australia's biggest company closed the week at $154.21, roughly 24% short of June's $192 all-time peak.

Large cap miners were mixed, with BHP and Fortescue lifting on Friday, while Rio Tinto dropped 1.5% to $138.47 despite a broadly positive trading update, which boasted higher production guidance, cost-cutting and asset sales.

The gold price has held relatively steady since Monday helping most ASX-listed miners push higher in the week's last session. IGO Limited was the top-200's best performer, surging more than 7% on Friday on the back of renewed interest in battery minerals, particularly in China. Lithium miner Liontown also charged 4.2% higher.

Shares in Hancock Prospecting-backed Arafura Rare Earths ended the session flat at 26.5 cents, after shareholders passed a plan to raise up to $70 million in a share purchase plan.

Energy stocks slipped 0.6% on Friday but ended the week 2.4% higher, supported by firming crude prices as Ukraine-Russia peace talks provided no signs of ending the conflict.

Consumer discretionary stocks were session's worst performers as Premier cratered almost 16% to $15.22 with a grim consumer spending outlook weighing on guidance.

It wasn't a great day for the broader sector, with Wesfarmers (-1%), JB Hi-Fi (-1.4%), Eagers Automotive (-3.6%) and Nick Scali (-4%) all fading.

Consumer staples traded just below flat, but lost 1.4% for the week as investors mulled the rising probability of interest rate cuts in 2026.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

Global shares rose over the last week, as the markets digested the rebound from November’s low but with optimism about a Fed rate cut providing support. For the week US shares rose 0.3%, Eurozone shares gained 0.7%, Japanese shares rose 0.5% and Chinese shares rose 1.3%. The muted US lead and the cross current of rising talk of RBA rate hikes but improving local earnings growth expectations saw Australian shares rise by just 0.2% for the week with strong gains in resources shares but falls in most other sectors. Bond yields rose, not helped by increases in Japan on rate hike expectations and concerns about an unwinding of the Yen carry trade. Australian bond yields also rose on increasing expectations for RBA rate hikes.

The recovery in Australian economic growth continues. While September quarter GDP growth at 0.4%qoq was soft, the details were strong. Annual growth perked up to 2.1%yoy its fastest in two years, the softness in the quarter was due to a 0.5% detraction from inventories but domestic final demand rose a strong 1.2%qoq with private demand also up 1.2%qoq, there were strong increases in dwelling investment and business investment helped by the data centre boom and household saving rose.

There was also some good news with productivity rising four quarters in a row and up 0.8%yoy and real household disposable income (a proxy for living standards) looking healthier.

Some concerns though were that consumer spending slowed with discretionary spending falling and public sector demand growth remained strong at 1.1%qoq. The former suggests that the consumer remains a bit fragile and dependent on discounting events (of which there weren’t any in the September quarter), but the household spending indicator showed a bounce in October with more promotional events. The latter is a concern as public spending remains around a record 28.5% of GDP and is likely adding to capacity constraints, leading to lower productivity than would otherwise be the case and by competing with the private sector for resources is likely leading to higher inflation and interest rates than would otherwise be the case.

All up, it looks like the recovery is continuing which along with the rise in inflation since mid-year will further add to RBA concerns that the economy is bumping up against capacity constraints and so looks likely to keep interest rates on hold for the foreseeable future.

Looking ahead, the US Federal Reserve is expected to cut rates next week.

Curated by James Gruber and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

Monthly Investment Podcast by UniSuper

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

Listed Investment Company (LIC) Indicative NTA Report from Bell Potter

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website