This article is an abridged extract of GQG Partners’ recent long-form article “Dotcom on Steroids”. You can read the full article here.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the US technology sector has been the standout investment trade, defying the concerns of value investors over steep valuations.

While many initially underestimated the business quality, growth runway, and long-term earnings power of big tech, these companies—led by visionary founders—evolved into monopolistic giants, delivering fast growth and robust profit margins. In a growth-starved, zero-interest-rate world that continuously drove capital toward secular growing compounders, this was the perfect setup for massive outperformance.

Today, we believe the sector stands at a significant inflection point, with investors seemingly making a one-way bet on the AI mania while appearing to ignore alarming fundamental issues.

GQG’s investment philosophy is grounded on the idea of “Forward-Looking Quality.” For the first time in our firm’s history, we believe many large technology companies today—particularly those with meaningful roles in the AI infrastructure build-out—represent backward-looking quality.

As a result, we have adopted a much more cautious stance toward these investments. We anticipate the next few years for the sector will be defined by deteriorating fundamentals: lower growth, higher competition, and greater capital intensity.

1. Lower growth

The remaining runway in most technology end markets is an issue, in our view. Once a company becomes the proverbial 800-pound gorilla in its respective sector, sustaining supernormal topline growth tends to be virtually impossible.

How fast can Microsoft or Nvidia grow now that they respectively control approximately 60% of the entire software and semiconductor industry’s profits? On the current trajectory, we would not be surprised to see long-term revenue growth decelerate to single digits within the next five years.

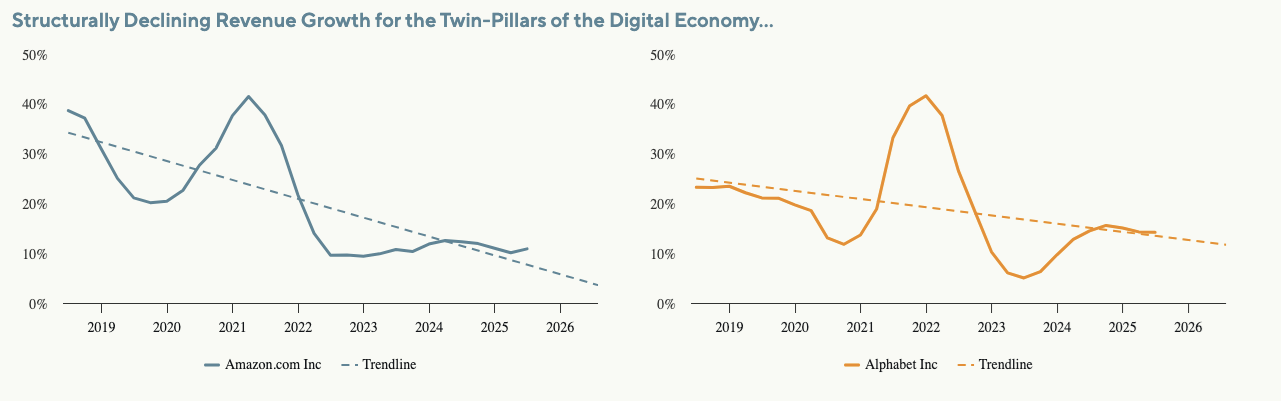

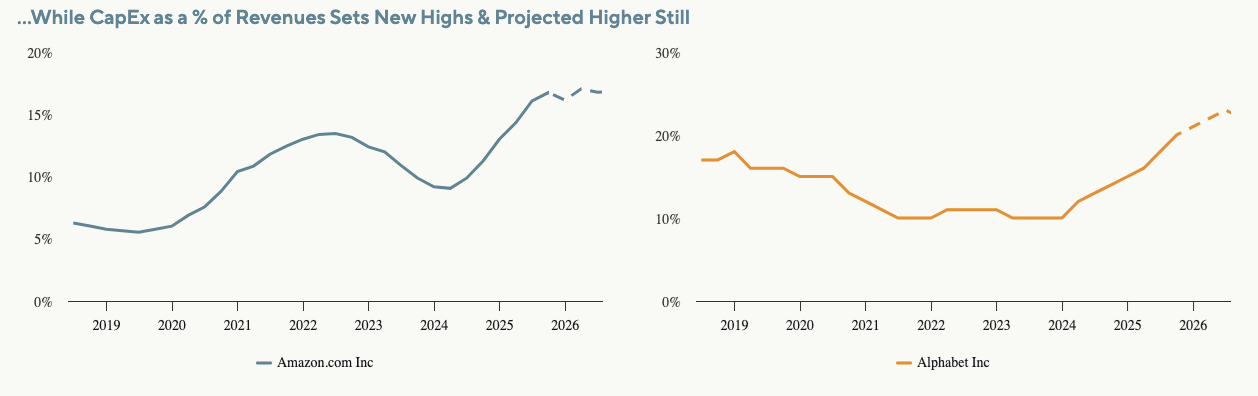

In other words, we believe big tech no longer offers a unique growth profile relative to other sectors. Indeed, a few of these larger spenders like Amazon and Alphabet have been trending in that direction for some time, all the while their capital expenditures as a percentage of sales sets new heights.

To be clear, these are names we have owned in the past in a big way—and very well may own in the future when the visibility improves—but at the current juncture we remain cautious.

AI expenditure is linked to advertising spend

Most of today’s AI capital expenditures are funded by advertising revenue—the lifeblood of Silicon Valley.

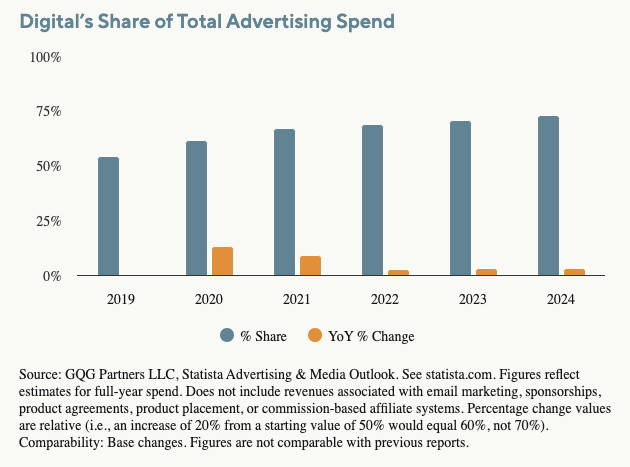

Digital advertising now accounts for more than 70% of all advertising, so the penetration-driven growth story could be approaching its final innings. Morgan Stanley expects the US digital ad industry to grow at a 9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2025 to 2030—less than half of its 20% CAGR between 2014 to 2019.

At these rates, we believe the sector may only grow in line with sleepy sectors—think transmission and distribution utilities or property and casualty insurance—yet with considerably higher risk and cyclicality.

2. Competition has structurally increased

During the 2010s, we viewed big tech as a collection of monopolies: Amazon dominated e-commerce, and Google dominated search. Their only competition came from sleepy incumbents ripe for disruption, such as cable television or brick-and-mortar retailers.

That is no longer the case today. Instead of playing in different sandboxes, big tech has largely converged into the same AI arms race, where they now compete directly against each other.

For example, countless new competitors have entered the digital advertising sector, including Walmart, Netflix, and Uber. Chinese internet companies have also become fierce global competitors. In fact, ByteDance recently surpassed Meta to become the biggest social network by revenue worldwide.1

At the end of the day, ad budgets are finite, and tech companies are increasingly competing against each other—rather than legacy media companies—for incremental growth.

Despite massive innovation over the past century, total advertising revenue has remained constant at around 2% of GDP,2 and we do not believe AI can change this fact. Moreover, there are only 24 hours per day, placing a natural limit on how much each digital platform can monetize users.

Clouds on the horizon

Another great example of the deteriorating competitive landscape is the cloud market, which has been one of the most important growth drivers for several tech giants.

This was once a stable three-player market: Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet. However, a disruptive fourth player (Oracle) just entered in a big way and is explicitly undercutting peers on pricing by 40%, according to our research.3 Adding to the shakeup, CoreWeave—a financially constrained fifth player with an arguably more cutting-edge product—has announced its intention to aggressively gain market share through pricing pressure.

Such dynamics have the potential to make life difficult for even the most established players. AWS, for instance, is already showing signs of competitive strain. Its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margins declined by a staggering 7% last quarter, while earnings growth slowed to a pedestrian 9%. That is hardly the picture of robust performance for a stock trading at 30x forward earnings, in our view.4

Competition will likely only increase with sovereign cloud players and startups all simultaneously ramping up supply. In fact, China is already experiencing a massive datacenter oversupply, resulting in only 20%-30% utilization rates.5

The cloud market now reminds us of the telecom industry, another highly capital-intensive business. Historically, we have observed that telecom economics typically deteriorate when a fourth player enters the market, particularly if it competes on price.

While there are some switching costs with cloud, we do not believe they are insurmountable, as plenty of companies have changed providers in the past. For example, ServiceNow and Salesforce recently signed large deals with Google Cloud, representing a shift away from industry leaders Amazon and Microsoft.6,7

It is also unclear how much of the cloud sector’s revenue growth now comes from AI startups, which are typically funded by the same cloud companies. According to one estimate, AI startups spend more than 80% of raised venture capital money on compute resources.8 If VC funding dries up, a substantial slice of the cloud sector’s incremental spend could be at risk, potentially slowing growth.

Tech faces substantial disruption risk

In the 2010s, big tech were the disruptors. Today, big tech is the incumbent, while AI is emerging as a highly disruptive force. It is not obvious to us who will be the biggest winners from AI over the next decade.

Even in the internet era, the biggest winners only became apparent many years after the bubble burst (e.g. Meta, Google). As a result, we believe investors are not adequately pricing in the risk of disruption.

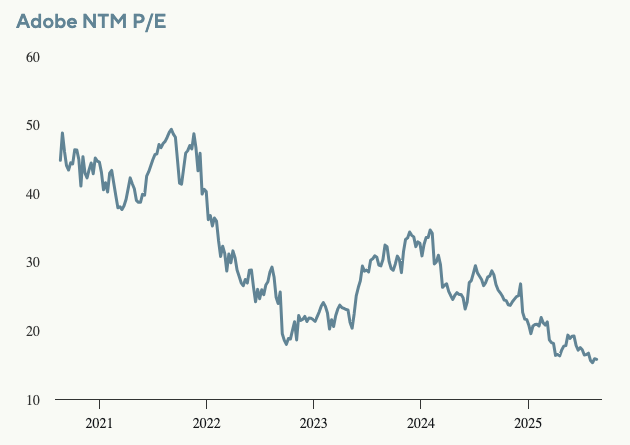

Google’s dominance in search is being challenged by AI advancements like ChatGPT, while software’s once-sticky dynamics are facing erosion, as seen in Adobe’s sharp de-rating from 50x to 15x earnings per share (EPS) despite robust earnings growth. These shifts highlight how quickly market narratives can unravel.

3. Capital intensity has structurally increased

The third pillar of the big tech thesis during the 2010s was hyper scalability.

Unlike most industries, big tech grew rapidly without requiring much incremental investment, allowing them to generate substantial free cash flow. For example, Google raised up to $50 million from inception through its IPO—a figure that would be unimaginable today. Similarly, Meta essentially required no incremental investment for each new subscriber.

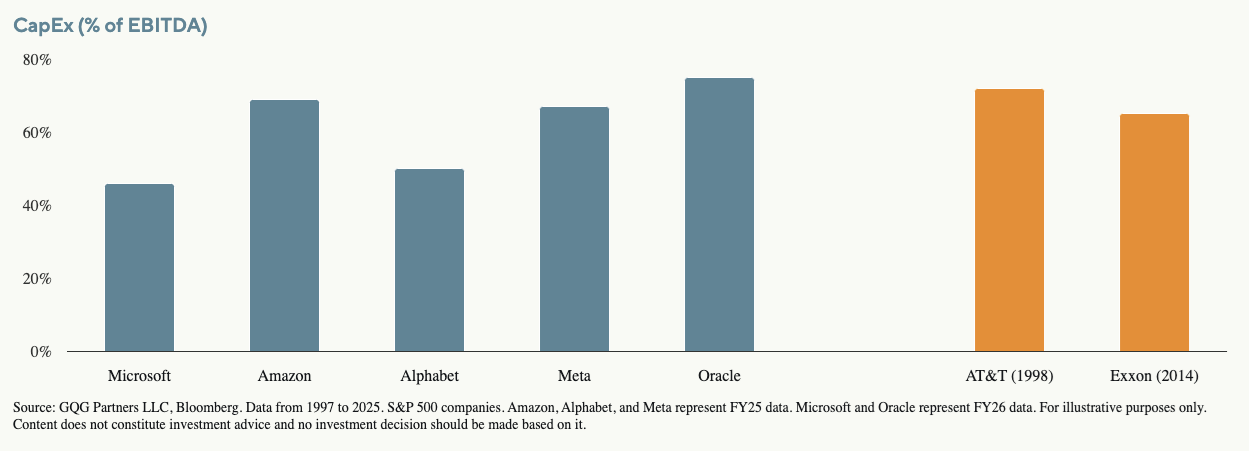

This argument no longer holds true in the AI era. Big tech CapEx as percentage of EBITDA is now running at 50%-70%, which is similar to AT&T’s 72% at the peak of the 2000 telecom bubble and Exxon’s 65% at the peak of the 2014 energy bubble.

In other words, AI CapEx has already caught up to prior bubble levels, even after adjusting for big tech’s initial high margins. And historically, companies experiencing higher capital intensity tend to be structurally poor investments.

In both the telecom and energy bubbles, an exciting new technology (internet for telecom, shale for energy) justified unprecedented levels of investment. Eventually, supply outstripped demand, and the companies never earned a return on their investment, as discussed in our GQG Research Software is the New Shale9

We believe that a similar scenario could unfold with AI over the longer run, but in the short and medium term, the signs are questionable.

ChatGPT launched nearly three years ago, yet revenues for the “AI Natives”, estimated to be less than US$20 billion today10, still pales relative to the approximately US$7 trillion datacenter CapEx expected by 2030.

Many potential monetization angles, such as AI smartphones, have ended up being flops thus far. In our view, this is far worse than the internet bubble, which at least generated meaningful revenue.

Structurally lower returns on capital?

We believe today’s intensive AI CapEx may structurally reduce returns on capital for the entire sector. Indeed, this is exactly what happened to the telecom sector during the 1990s fiber rollout.

Contrary to popular perception, telecom used to be a highly profitable sector made up of regional monopolies up until the mid-1990s. However, the combination of massive CapEx and increased competition permanently impaired the sector’s economics by the late 1990s.

We think the fatal flaw was adopting a “if you build it, they will come” strategy, where telecom providers assumed new applications would get developed to take advantage of the excess bandwidth. In the end, the killer internet apps eventually popped up years later, but by then, it was already too late for the telecom sector.

We believe that today’s surge of datacenter CapEx and cash-burning AI startups could end similarly to the telecom bloodbath from 25 years ago. In today’s AI arms race, any company that does not buy the latest generation of technology may quickly be at a disadvantage. This is why companies like Oracle are now spending more than 100% of their operating cash flow on CapEx.

To date, big tech has been able to mitigate the impact of massive CapEx spending on their earnings by repeatedly extending the depreciation periods for their investments. We believe that current depreciation numbers are grossly understated as the hyperscalers need to keep buying the latest Nvidia GPU models, which are released annually, to stay competitive.

Once reality sets in, investors may find that earnings are massively inflated due to much higher depreciation.

A closing question

We are not perma-bears on the technology sector; in fact, we were comparatively larger buyers of Nvidia in 2023, and the stock has been among the top performers since the firm’s June 2016 inception11. However, our views on the sector have since shifted.

Given our goal of capital preservation during downturns and our natural inclination to forgo some upside possibilities in favor of maximizing potential long-term compounding, we would be remiss if we did not raise the question:

How much of your net worth do you want invested in a cyclical sector where many of the largest players appear to be exhibiting growth deceleration, free cash flow margin deterioration, and increasing competition?

In our view, big tech no longer offers the unique growth it once did, yet it trades at lofty 30x-50x free cash flow multiples. We see better opportunities outside the tech sector.

1Hu, Krystal. “ByteDance surpasses Meta, plus Jensen Huang’s fruitful trip in Beijing”Reuters. 17 July 2025.

2Marto, Ricardo. Le. Hoang. “The Rise of Digital Advertising and Its Economic Implications”. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 10 October 2024.

3Source: GQG Research .

4Source: AWS 1Q2025 earnings call. Bloomberg.

5Reuters. “China plans network to sell surplus computing power in crackdown on data centre glut”. July 2025.

6Butler, Georgia. “ServiceNow signs $1.2bn contract with Google Cloud – report”. Data Center Dynamics. July 2025.

7Butler, Georgia. “Google Cloud wins $2.5bn contract from Salesforce”. Data Center Dynamics. February 2025.

8Appenzeller, Guido. Bornstein, Matt. Casado, Martin. “Navigating the High Cost of AI Compute”. Andreessen Horowitz. April 2023.

9Walker, Peter, Young PhD, Michael, Dowd, Kevin. “Q1 2025 VC Fund Performance Report.” carta.com. 17 June 2025.

10GQG Research. “Is Software the New Shale?”. GQG. December 2022.

11Agnew, Harriet. “AI will create ‘more losers than winners’ even as Nvidia soars”. Financial Times. June 2023.

This is an abridged extract of GQG Partners’ recent long-form article “Dotcom on Steroids”. You can read the full article here.

This article contains general information only, does not contain any personal advice and does not consider any prospective investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making any investment decision, you should seek expert, professional advice.