There’s an unspoken pact in Western countries including Australia that each new generation will be better off than the last. Will that be the case this time around?

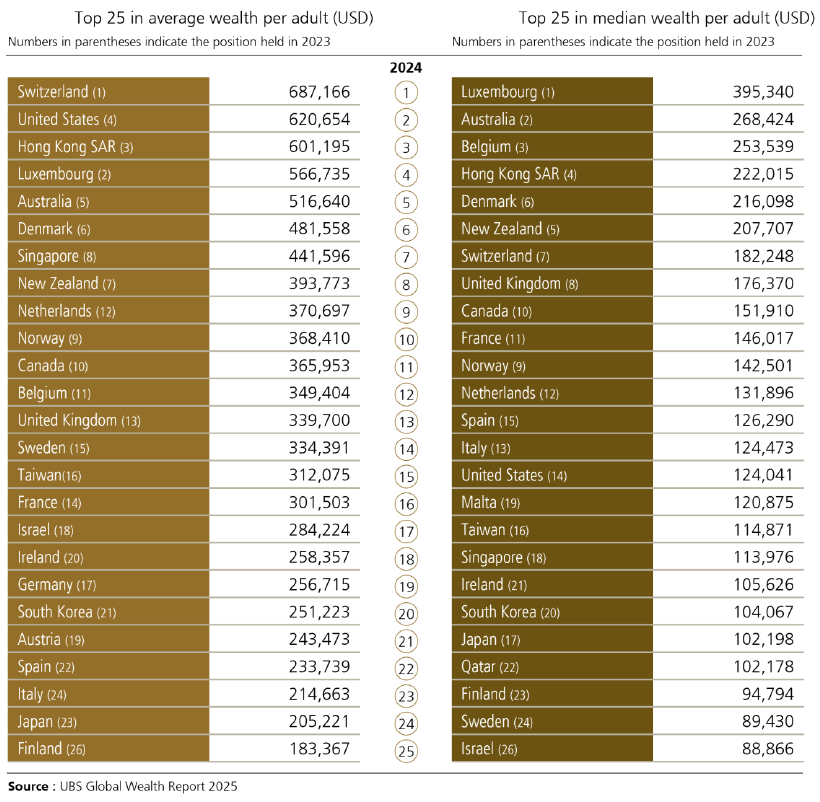

There’s an existential angst among young and old today that our kids will be worse off than their parents. On the surface, the angst seems hard to fathom. After all, Australia is wealthier than ever. According to UBS, our wealth grew 11% in 2024, and we rank second for median wealth per adult in the world.

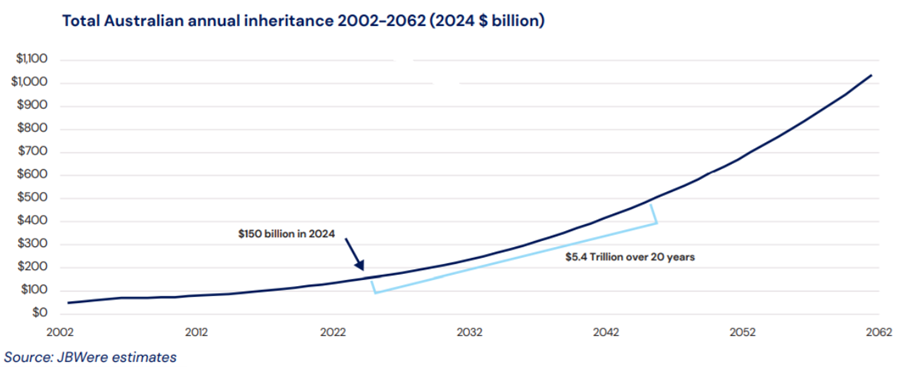

It’s true that much of this wealth resides with older Australians. Yet, JBWere estimates that some $5.4 trillion of this wealth will be transferred to younger generations over the next two decades.

What’s the problem, then? Well, dig a little deeper and the prospects for our young may be more tenuous.

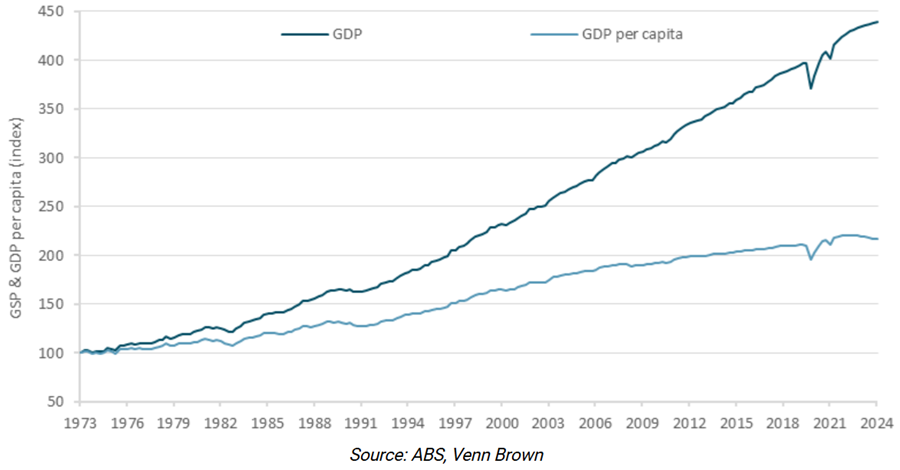

First, living standards have stagnated in Australia over the past decade. While economic growth has risen, it’s mostly been driven by increased immigration. On a per capita basis, GDP is barely above 2015 levels.

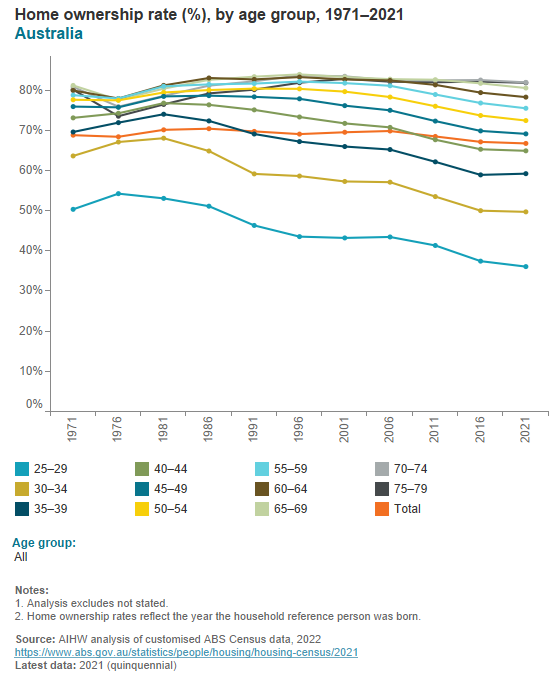

Wages have struggled to keep up with inflation. Meanwhile, costs in essentials such as groceries, education, and housing, have soared since Covid. That’s resulted in record university debts and declining levels of home ownership for younger age groups.

Tightening belts

The strains on the young show up in household spending data.

KPMG says that younger Australians are pulling back on recreational spending to cover costs like mortgage repayments, rent and other essential expenses, while older Australians are enjoying more travel and dining out.

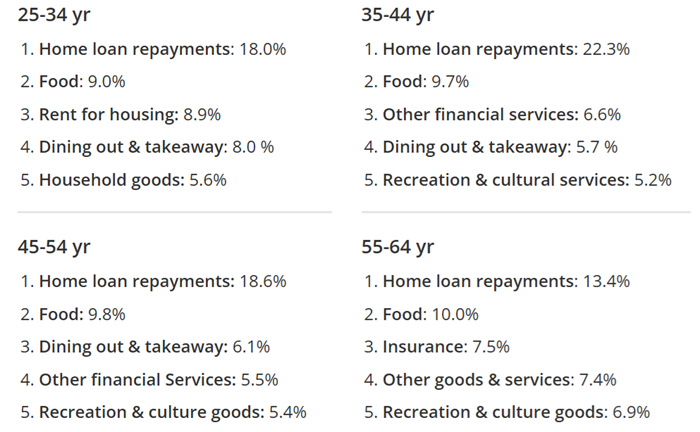

The top five categories as a percentage of household spending for each age group in 2023-24 were:

Note: the data captures the average spend of a household and does not reflect the average spending of an individual. Source: ABS: KPMG.

While the top expenses for all Australian households continue to be mortgage repayments and good, 25–34-year-olds are spending more on rent than any other age group, highlighting the declining homeownership rates of this generation.

KPMG Urban Economist Terry Rawnsley says that “we are witnessing the rise of 'Generation Rent’, with saving for a deposit and servicing a home loan increasingly challenging, especially in our capital cities.”

It may not be all bad

A new report from thinktank, E61, ‘Will young Australians be better off than past generations?’, suggests negativity around the outlook for younger generations may be overdone.

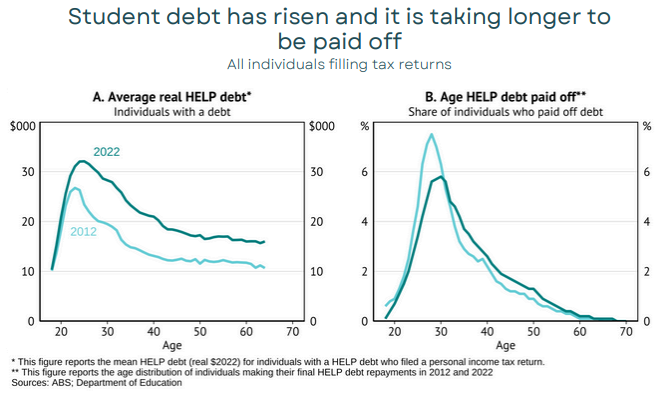

It admits that the young are more indebted. Since 2012, the number of Australians under the age of 35 with a HELP loan has risen from 20% to 30%. The average size of these debts has also increased by more than 30%, reaching $26,463. And younger people are taking longer to repay their loans. The average age for final repayment of loans has grown from 32.7 in 2012 to 34.8 now.

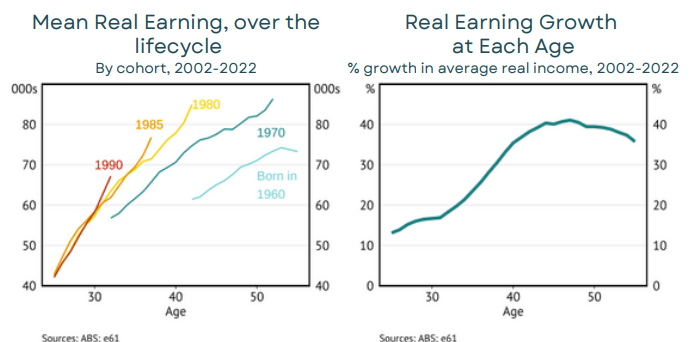

And wage growth has been slow. The report says that since the GFC, workers under the age of 40 have seen their income grow by less than half the rate of those aged over 40. This trend has puzzled economists, who offer a variety of potential explanations, including rising underemployment, a shift toward more casual work, pay award decisions, and an oversupply of workers relative to available high-quality jobs.

Also, the report says that while the jobs market has been strong, it’s benefited women more than men. The unemployment rate for men aged 15 to 24 is 10.6%, far higher than their female counterparts at 8.3%. E61 partly puts that down to a structural decline in traditionally male-dominated industries such as construction, manufacturing, and mining.

The report notes that opportunities to get ahead in regional areas have also become more difficult. More than 10% of young people are neither in full-time study nor work, compared to 7% in capital cities. For young men in the country, this share has increased from 5% in 2000 to 9% now.

Finally, E61 acknowledges that homeownership rates among the young are declining. Today’s 25- to 34-year-olds have lower home ownership rates than their parents when they were the same age, with a greater disparity in capital cities.

Despite these challenges, the report says there’s room for optimism. In many ways, young Australians have access to opportunities that weren’t available to their parents and grandparents.

Today, they’re better educated, earn more in the early stages of their careers, and have more diverse and flexible job paths. Young people are also benefiting from tremendous technological advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, and the like, which is giving them greater access to information through the internet, improvements in the availability of digital goods, and cheaper consumer goods.

Younger people are also building superannuation balances over longer careers at higher rates, and many of them will inherit a slice of the $5.4 trillion intergenerational wealth transfer over the next 20 years.

Lastly, the report makes the point that changing patterns in consumption and wealth-building mean economic achievements, like moving out of home, buying a house and starting a family – are still happening, but they’re often occurring later in life than with previous generations.

What should governments do?

The report says policymakers should consider the following to ensure younger people are better off than previous generations:

1. Don’t jump at shadows.

E61 says young people may still experience traditional markers of economic security and adulthood but just later in life. Distinguishing between what is temporary, what is permanent, and what reflects a change in people’s preferences will be important. One risk is in assuming that younger people should have things at the same time as previous generations. That may not be the case.

2. Beware one-size fits-all solutions

The report says that this generation’s journey toward adulthood is far from uniform. It thinks gender and geography are key factors shaping outcomes for young Australians. That being the case, it will be important for governments to provide specific solutions rather than generic ones.

3. Manage economic and social trade offs

Change brings benefits and costs. For instance, technology is a wonderful advance though there’s also evidence that it’s impacting the mental health of young people, especially young women. Governments will need to be aware of the potential tradeoffs to future policies to help the young.

It doesn’t address the big issues

While the E61 report is a balanced one, its conclusions are vague and don’t consider the two issues that can most improve the lives of younger people: making housing more affordable and improving living standards via better productivity. Get these things right, and the young will be better off than their parents. Get them wrong, and the current challenges will only get worse.

Neither is an easy fix, though we’ve discussed some of the potential solutions in articles (here, here and here) in recent weeks.

James Gruber is Editor of Firstlinks.