From 1st December it [the US Federal Reserve] is to stop quantitative tightening, i.e., the policy of actively reducing the size of its securities holdings and balance sheet. The present phase of QT [quantitative tightening] began in spring 2022 – and more forcefully in autumn 2022 – as part of the Fed’s then campaign to curb the USA’s inflationary pressures. This QT approach contrasted with the quantitative easing it pursued in the two years from early 2020 and, in an earlier cyclical episode, from 2009 to 2014.

Quantitative easing had – in that earlier episode – been intended to support economic activity, and to obviate the adverse impacts on output and employment of the Great Recession. In my latest book Money and Inflation at the Time of Covid I argue that the QE exercise in the early 2020s was responsible for an explosion in money growth and was the main causal driver of the subsequent increase in inflation. On the other hand, QT from early 2022 reduced the quantity of money. In fact, the US quantity of money (on the broadly defined M3 measure) fell for much of 2022, while in the two years to March 2024 it was roughly unchanged. According to the analytical framework (of “broad-money monetarism”) developed in Money and Inflation at the Time of Covid, as well as a large body of earlier work from me, the change from rapid money growth in 2020 and 2021 to money stagnation in the two years from spring 2022 ought logically to have been associated with a marked deceleration in inflation. Indeed, I said as much in my regular Institute of International Monetary Research commentary in May 2022. This duly happened, with inflation at the end of the Biden Presidency coming back towards the Fed’s 2% target.

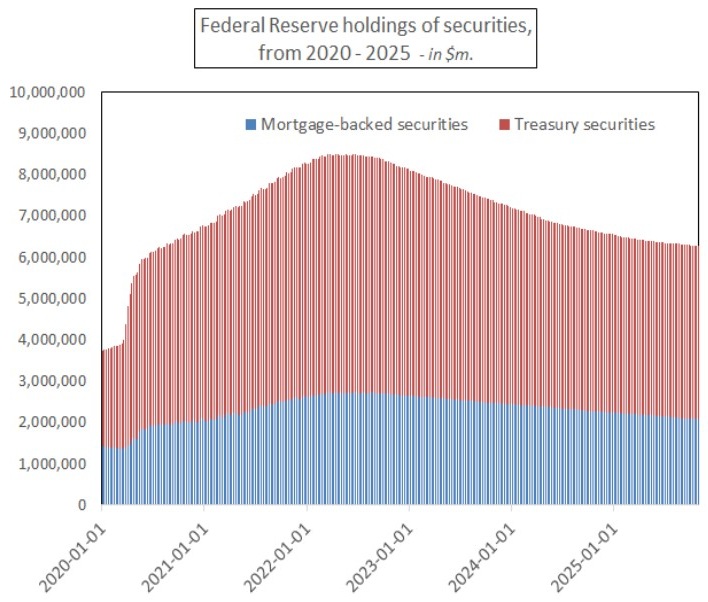

The chart below shows the story in the 2020s of the effects of its open market operations on the Federal Reserve’s holdings of securities. The surge in those holdings in April 2020 – of almost $1,350b. in the four weeks to 15th April, from $4,007.5b. to $5,357.0b. – is evident. It was the dominant reason that broad money surged at that time. In fact, in the one month of April 2020 M3 broad money jumped by 7.4%, more than in any full year in the 2010s. (I use the M3 number estimated by the Shadow Government Statistics consultancy, to whom my thanks.)

The purchases of securities were smaller in the following months, but QE continued to spring 2022, when on 13th April the Fed’s holding of securities peaked at a remarkable $8,502.2b. But the chart also brings out that spring 2022 was the watershed between excessive money growth and a marked monetary constriction. Between 13th April 2022 and 15th May 2024 the Fed’s holdings of securities dropped from $8,502.2b. to $6,860.1b. Its holdings of Treasury securities plunged between the two dates from $5,762.1b. to $4,488.1b., as the US national debt was increasingly held outside the banking system in the hands of long-term investors. The shrinkage of the Fed’s Treasury bond total coincided with a rise in the US budget deficit, because of President Biden’s so-called “expansionary fiscal policy”. Needless to say, bond yields rose as long-term investors had to absorb both the new debt from the deficit and debt being jettisoned by the Fed.

Managers of the US public debt are finding it harder to market their wares as the years of deficit continue. In recent commentary I pointed out that total assets held by money market mutual funds on 15th October 2025 were $7,367.3b., 14.9% higher than on 16th October 2024, with the difference between the two dates being $899.5b. After a regulatory clampdown following the Great Financial Crisis, MMMFs [money market mutual funds] are allowed to hold only kind of new asset, claims on the US Treasury with less than a year to maturity. (By holding such claims – which are taken to be very safe – the MMMFs can always repay depositors at 100 cents in the $. The worry had been that in the GFC they came close to “breaking the buck.”)

But it is obvious that the MMMFs – with their almost $900b. balance-sheet expansion in the year to mid-October – are now crucial to the financing of the US Federal deficit of about twice the size. It has to be emphasized that MMMF funding is very short-term in character, while the liabilities of MMMFs are quasi-monetary. The debt isn’t being financed from the central bank and in that sense American policymakers are not “resorting to the printing presses”. But – in my view – selling paper of less than one year to the MMMFs is monetary financing of the deficit. (Readers might wonder what has happened since 15th October. The answer is that MMMF assets on 29th October were $7,418.3b. The annualised growth rate in the fortnight was 19.6%. The message of the analysis is unchanged.)

Assume the US Federal deficit is $2,000b. in the 2025/26 fiscal year (i.e., that running from October 2025 to September 2026). If $1,500b. of that is financed from the commercial banks and MMMFs, I would suggest that the positive effect on broad money (now about $30,000b. on the M3 measure) would be roughly 5%. If banks are also growing their loan books, broad money growth will be more than 5%.

The importance of the Fed’s latest announcement becomes clear. Without QT acting to reduce the quantity of money and hence the rate of money growth, the expectation has to be that the annual rate of money growth will be in the high single digits, i.e., with a typical rate of increase of 6% - 8%. This is too high to be consistent with 2% inflation. Instead, while monetary policy settings stay as they now are, annual inflation is more likely to be in a 2% - 5% band. The Fed will fail to bring inflation back to the kind of figures deemed normal for most of the last 30 or so years. The basic underlying problem is that the large budget deficit is in conflict with anti-inflationary monetary policy.

My claim here may challenge the consensus view. Well, so what? My correct forecasts of almost double-digit US inflation in early 2020 were an application of (what I regard as) an organized and successful theory of the determination of nominal national income and inflation. My current prognosis is just another application of that theory.

Professor Tim Congdon, CBE, is Chairman of the Institute of International Monetary Research at the University of Buckingham, England. Professor Congdon is often regarded as the UK’s leading exponent of the quantity theory of money (or ‘monetarism’). He served as an adviser to the Conservative Government between 1992 and 1997 as a member of the Treasury Panel of Independent Forecasters. He has also authored many books and academic articles on monetarism.

This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.