In many years of involvement with investments, I've never known investors to be as unconcerned about the risk of inflation, both for the short term and in the longer haul, as they are at present, especially since:

- Even a small hint of prospective inflation in the US - where jobs are growing at the rate of more than a million each four months – would cause the Fed to raise its cash rate and bring about a likely sell-off in bonds around the world.

- There’s too little thought being given to the next cyclical upswing in global inflation, which, when it comes, will likely do a fair bit of damage to longer-term investments and hurt many self-funded retirees.

In my view (shaped, no doubt, by having lived through a half-dozen or so cycles in inflation, some big and some small), investors should always keep a watch on prospects for inflation. They should be prepared for the changes in investment strategy that swings in inflation require.

Will near-zero inflation continue for several more years?

The record lows in bond yields in the US and most other countries reflect three main influences: bond purchases by major central banks under their programmes of quantitative easing financed by printing money; very low cash rates; and expectations on the part of many investors that inflation will remain non-existent for several more years at least.

A recent paper by members of the Deutsche Bank research team in New York entitled “Why do market views on inflation differ from the Fed’s?” brings out the current extremely low expectations of inflation held by the Fed and - even more so - by investors in US bonds.

Each few months, the Fed carries out a survey of the individual forecasts its senior people have for inflation, economic growth and the cash rate. The results are released but names are not revealed. In the most recent survey, the median forecast for US inflation was running below the Fed’s target rate (of 2% a year) in each of the next three years.

The report then looked at estimates for future inflation as implied in the pricing of bonds and as derived from surveys of investors. It finds that inflationary expectations in the US bond market “imply that the Fed will not be able to reach its 2% inflation goal in the next five to ten years”.

The authors of the report see significant risks US inflation will return sooner than the Fed is forecasting and much earlier than the bond market anticipates. They conclude “While the overall economy may still be a year or more away from reaching full capacity and over-heating, wage inflation appears already to be on an upward trend”. Even with the strong US dollar and low inflation in other countries, “a year from now, upward pressure on wages and prices should be noticeably more intense than they are today”.

My worry is there could soon be a hint of inflation, most likely in figures for labour costs, that causes a cyclical sell-off in bonds and a noticeable wobble in share markets, in the US and around the world. Maybe, the 0.5% jump in February 2015 in yields on ten year US bonds (to a still-skinny 2.15%) is an early sign of what’s coming up by year’s end.

When there’s a near-unanimous view that inflation will be close to zero, it doesn't take much to cause a swing in expectations and a rush to the exits.

The risk of inflation in the medium term and long term

There’s another way in which the risk of inflation – this time in the medium term and longer – isn’t getting the attention it deserves. Sudden increases in inflation inflict pain on long-term investors – especially self-funded retirees.

The current downplaying of prospective inflation is easily understood: here and overseas, there’s not much inflation. It’s always tempting, and generally dangerous, to project ahead a recent experience and call it a lasting trend.

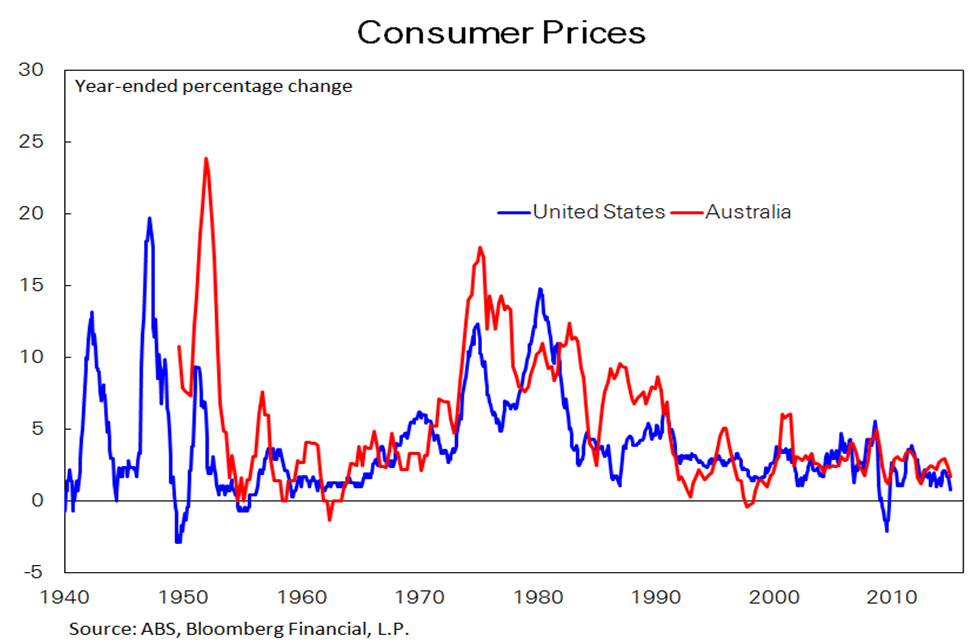

My chart shows inflation in the US and Australia over seven decades. The correlation between the inflation rates of the two countries is higher than is generally thought, despite many differences in wage-fixing arrangements in the timing of economic cycles, and despite big swings in the exchange rate. Correlation isn't necessarily causation, but US (and global) inflation seems to have a strong influence on Australian inflation.

The huge increases in inflation in the early post-war years and in the 1970s dominate the chart. Both outbursts of inflation followed (with lags) massive increases in the global money supply caused, in turn, by the monetisation of government bonds issued during the second world war, and the creation of US dollars as the US simultaneously engaged in the Vietnam War and spent on programmes for the ‘Great Society’. Of course, there were also special factors, such as in Australia’s case the boom in wool prices caused by the Korean War and the many goals the Whitlam government was pursuing.

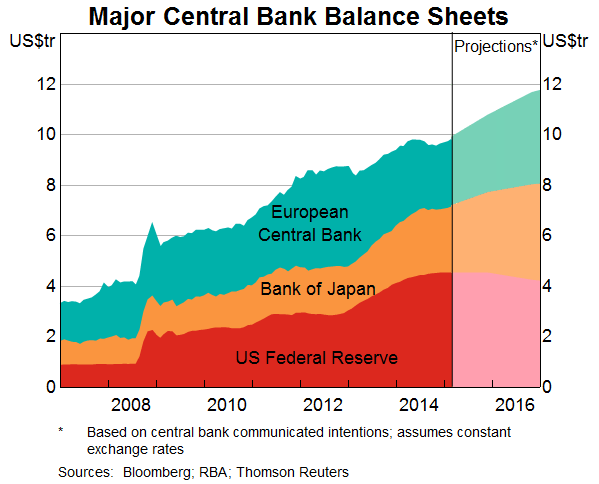

The global money base is again surging as the major central banks create money to purchase assets from the private sector. The combined balance sheet of the central banks of the US, Japan and Europe has expanded from US$3.5 trillion in early 2007 to US$10 trillion today – and there’s more to come.

Will inflation take off again?

After the last two bouts of rapid monetary expansion in the global monetary base, inflation took off. Will it happen again?

The Reserve Bank commented recently that “the current environment is one in which there has been a very large (global) monetary stimulus … (but) economic activity does not appear to have responded to the stimulatory monetary conditions in the way that occurred in the past and inflation rates have been very low. (However) global equity markets have been strong; property prices are again recording solid gains in some countries; and bond prices have increased substantially.”

The Bank offers two reasons why spending and inflation have responded so modestly to the global monetary stimulus: many households and businesses are keen to reduce levels of debt to finance spending; and “it seems probable that both workers and firms perceive that their pricing power has declined … (and reflects) a combination of the scarring experience of the financial crisis and of the increasing globalisation of many markets.”

In my view, the risks are the money creation by the major central banks will again bring about a cyclical rebound in global inflation, when world growth has picked up, memories of the debt overhang have faded, and banks are again lending money.

Anyone around in the 1970s and 1980s would recall the dislocation and losses the surge in inflation caused to investors. Bonds lost value as interest rates rose and inflation eroded the real value of interest payments and repayments of principal. Investors holding cash and term deposits also suffered in the inflation storm. Shares and property provided protection when inflation was low to moderate but investors lost out when inflation was rapid. Speculative and short-dated investments were favoured, and many long-term investments were sidelined.

The good news is that the next cyclical upswing in inflation is likely to be much milder than those of early post-war years and the 1970s, in part because central banks are more independent and wages are more attuned to economic conditions. Also, the range of investments has widened to include indexed bonds and infrastructure that offer inflation protection.

But we’re also living longer, have higher expectations of what we want to do in retirement, and fewer retirees have defined-benefits superannuation (with pensions adjusted automatically for inflation). As a result, even a mild cyclical pick-up in inflation in coming years would be damaging for long-term investing and a serious complication in retirement planning.

Don Stammer chairs QV Equities, is a director of IPE, and is an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund and Altius Asset Management. The views expressed are his alone. This article is general information and investors should seek professional advice on their personal circumstances.