The notion that the RBA ‘chooses to allow’ the ‘voluntary unemployment’ of several hundred thousand Australians is something that may come as a surprise to many. Yet that is precisely the charge levelled at the central bank in a tome from economist Ross Garnaut. He claims that such unemployment was a consequence of the RBA running monetary policy too tight after 2012.

Now Ross Garnaut is no slouch. He was a senior economic adviser to then PM Bob Hawke during the 1980s and has written extensively and thoughtfully on economic policy issues for decades.

However, the charge against the RBA is largely a specious one.

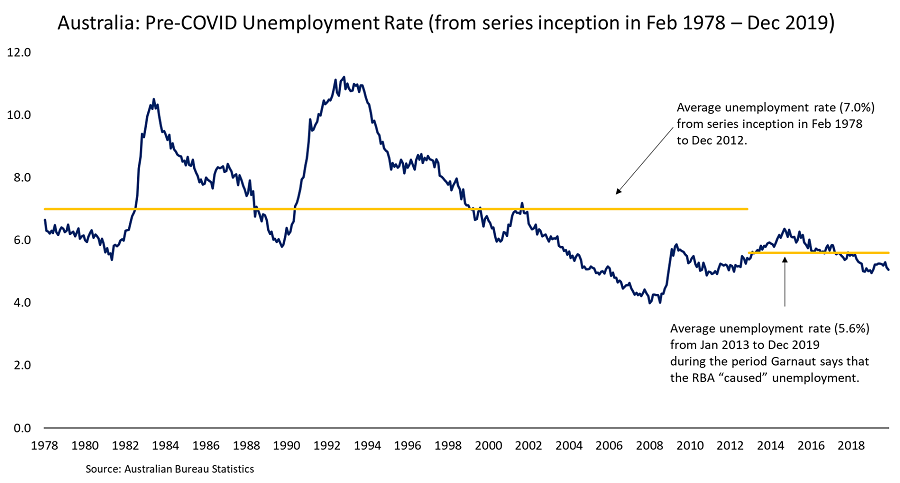

For one thing, the average monthly unemployment rate from February 1978 (when the current series was commenced) to the end of 2012 was 7.0%. From that point to the onset of the pandemic it was 5.6%.

It might be interesting to find out who Garnaut puts in the frame for the even greater levels of ‘voluntary unemployment’ in the decades prior to 2012.

It's not only about monetary policy

Of course, hindsight is a wonderful thing, and the RBA may have run monetary policy a little too firmly after 2012. It is also probably true that the time has come to move on from inflation targeting as the overarching focus for monetary policy. Perhaps to one that explicitly embraces, among other things, an employment objective.

In the scheme of things, the RBA’s ‘culpability’ for unemployment levels is not deserved of the prominence that Garnaut and others give it. That prominence derives from an unbridled but misplaced faith in the efficacy of macro policy and a corresponding reluctance to consider structural measures that enhance the economy’s flexibility and adaptability.

The political wherewithal to consider such measures reached their apogee under the banner of ‘microeconomic reform’ during Paul Keating’s Treasurership.

By the late 1980s, as the then Treasurer put it, “every galah in the petshop was talking about microeconomic reform”. That agenda extended through the 1990s during his Prime Ministership and into the early stages of the Howard Government. (To be fair to Garnaut, he does canvass, albeit selectively, some measures of this nature.)

Where are the microeconomic reforms?

It was those type of microeconomic reforms, including measures to enhance labour market flexibility, that drove the ‘natural’ rate of unemployment lower, to the ‘4 point something’ now articulated by RBA Governor Lowe as a potential ‘natural’ rate, or perhaps even as low as the 3.5% Garnaut now posits.

But the current tacit refusal of both sides of politics not only to assign such ‘microeconomic reform’ measures to the ‘too hard’ basket, but in some cases reverse those reforms, looms as a bigger potential culprit in occasioning higher unemployment than any ‘failure’ to adequately fine-tune macro or monetary policy.

For the most part, however, every galah in the petshop now persists in talking about nothing else other than how an (easier) twist in monetary policy, including a turn to the ‘unconventional’, is a pivotal part of a panacea for our perceived economic ills.

But monetary policy is limited in what it can achieve and should be just one increasingly minor part of the overall policy armoury. Key global central bankers, including Governor Lowe, have been trying to tell markets, governments and academia this very fact for some time – apparently to little avail.

Meanwhile, historically high levels of monetary accommodation have unleashed a plethora of ‘unintended consequences’, such as asset bubbles and growing wealth inequality, excessive risk-taking and attendant financial stability concerns. Easy liquidity sets ‘moral hazard’ traps that debilitate economic performance by allowing ‘zombie’ companies to persist, ultimately delaying necessary economic adjustment and lowering the economy’s growth path by inhibiting its productivity, flexibility and dynamism.

That is not to say there is no role for macro policy in a post-pandemic environment. But an assessment of that role should include a revisiting of the objectives of monetary policy and, more importantly, a recognition of its limitations.

We need to use all arms of economic policy

Central banks, including the RBA, are not perfect. The galahs in the pet shop – gratuitously - remind us of this all too often. But central banks need support from, and need to support, other arms of economic policy.

So, I do wish - just occasionally - that those aged petshop galahs would sometimes advance an advocacy of the agenda that they pushed in the 1980s. An agenda that ultimately set up Australia for a globally unprecedented three-decade long expansion and one that has the best chance of navigating the economy safely to and through the post-pandemic world.

Stephen Miller is an Investment Strategy Consultant with GSFM, a sponsor of Firstlinks. He has previously worked in The Treasury and in the offoce of the then Treasurer, Paul Keating, from 1983-88. The views expressed are his own and do not consider the circumstances of any investor.