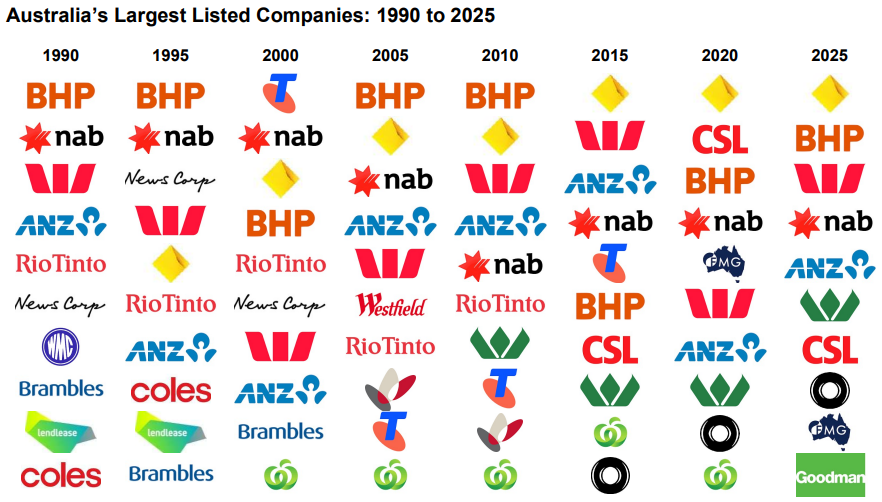

The major banks have been the mainstay of the domestic investment landscape in Australia for over 100 years. While credit cycles have come and gone, as the country has prospered and the population has grown, the banks have been a major beneficiary. Currently Australia’s top five companies by market capitalisation are the four major retail banks and BHP. The prominence of the banks is a phenomenon that has long been the case. In fact, looking at the largest 10 companies by market capitalisation every five years since 1990 demonstrates the longevity of this dominance. As a result, the banks make up a very large proportion of the exposure most Australians have to domestic equities. ANZ, Commonwealth Bank, National Australia Bank and Westpac constitute 22.6% of the ASX200.

The question is, should investors be this invested in the sector? Or, for the first time in a very long time, is there a competitive threat for the banks’ profits and business model emerging that the market might be underestimating?

For most of the last 50 years the fundamentals of banking have not changed a great deal. A bank is a relatively simple proposition. You need funding, which is typically in the form of a combination of bank capital, wholesale funding and deposits from clients with savings. The funding mix is influenced by regulatory capital requirements and the cost of the relative sources of funding. And then you lend this capital to borrowers. You charge borrowers more than you pay those providing the funding, with the bank earning the spread between these two rates, which is called the net interest margin. You then have expenses, such as employee, property, technology, marketing, commission, utilities and regulatory costs. There are also expected credit losses and realised losses on loans that have gone into default and are unable to be repaid in full. Deducting these expenses from the net interest margin earned and any revenue earned from trading and fees charged to clients gives you profit before tax.

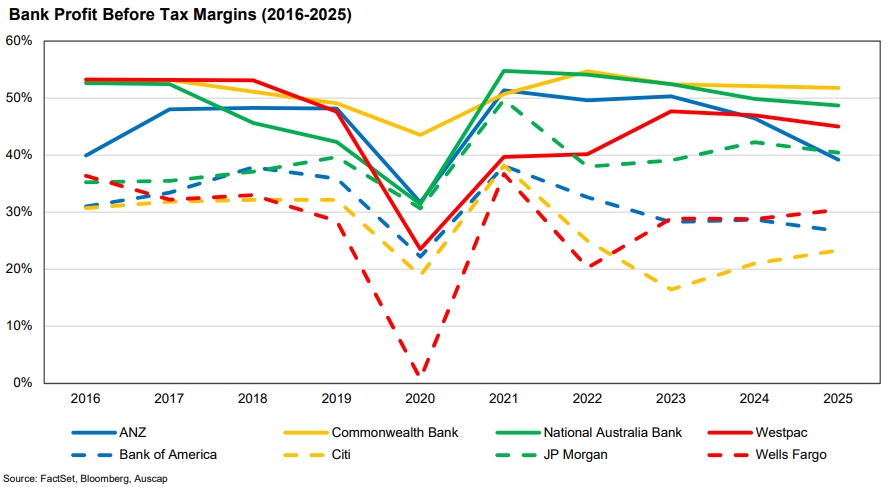

The largest four domestic banks have a combined market share of over 70% of gross assets held by financial institutions in the domestic market. As a result, these banks have had significant scale advantages that increase profitability. Profit before tax (PBT) margins is one way of assessing relative profitability of different banking markets. It represents profit before tax as a percentage of revenue. For the major Australian banks PBT margins have averaged 47.5% over the last decade.

This is high by international standards. In the United States, the largest four banks, JP Morgan, Bank of America, Citibank and Wells Fargo, represent less than 40% of the total domestic assets held by financial institutions. These four institutions have averaged PBT margins of 31.2% over the same time frame. This is despite JP Morgan’s elevated margins compared to peers, a function of its asset management and investment banking activities making it less comparable to traditional banks. There are over 4,000 banks in the US compared to less than 100 in Australia. In the United Kingdom, Lloyds enjoys market leadership with 20% of the domestic market, in the same way that Commonwealth Bank of Australia enjoys its market leading position domestically. Yet again, its PBT margins have averaged 38.8% over the last 10 years. There are between 300 and 400 banks in the UK. The more competitive markets in the US and UK have witnessed lower PBT margins.

Historically, to borrow money in Australia, whether you were a family trying to buy a home or investment property, or a business trying to fund growth, you required direct contact with the bank which would assess your application. This led to a banking relationship that was sticky and advantageous for both the bank and the customer. For the bank, the familiarity with the client reduced the risk of default. For the customer, the bank’s familiarity with them improved their chances of securing a loan and on potentially more favourable terms than offered elsewhere. Banking was therefore a relationship business.

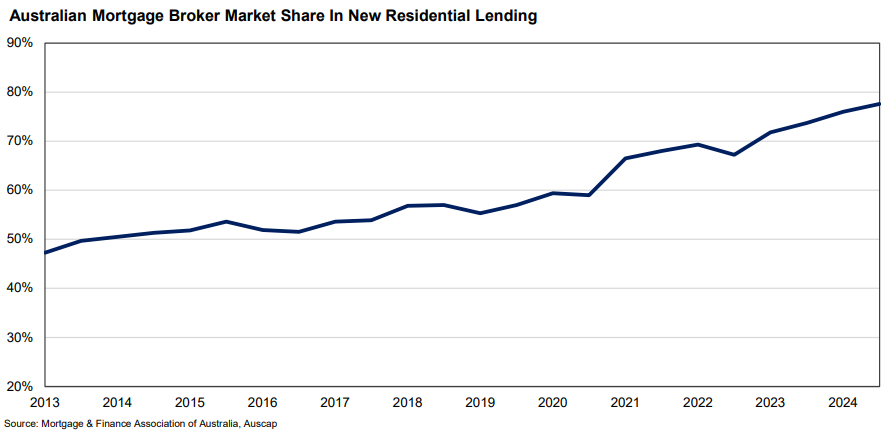

This traditional model started to change in the mid-1990s following financial deregulation. Mortgage brokers started to appear on the scene with the emergence of Aussie Home Loans and this accelerated with the emergence of other aggregators such as Wizard Home Loans in the early 2000s. Mortgage brokers rapidly became a very significant source of loan origination. By 2014, mortgage brokers were responsible for writing over 50% of residential mortgages. This percentage has since continued to climb. According to the Mortgage and Finance Association of Australia, in the September 2025 quarter, 77.3% of all new residential lending was facilitated by mortgage and finance brokers. This is 2.7% higher than a year earlier and 5.8% higher than in the September 2023 quarter.

We see this change as extremely significant. For many residential property borrowers seeking to take out a new loan, extend an existing loan or refinance, they now contact their mortgage broker, not the bank. The banks, by allowing mortgage brokers to gain such a dominant position, have forfeited their role as relationship manager with the client. This is an egg that is very difficult to unscramble. As a major bank, if you choose not to play in the mortgage broker space, you risk serious market share losses given they control more than three quarters of the market. But the problem is, if a competitor comes along with a lower rate and better terms for the mortgage broker who is writing the business, then it is fairly straightforward for that competitor to win share. Moving from one bank to another is relatively simple. The 'economic moat' around the end customer has been diluted significantly and, in many cases, it simply does not exist. For years this has not been a problem, because there has not been a serious competitor seeking to scale and compete with the big four banks. The cosy oligopoly resulted in mortgage pricing that allowed the banks to maintain their market share and handsome profits. The question is whether this is now changing with Macquarie competing aggressively for share.

On the other side of the ledger, banks have been charging customers very significant implied fees on at call deposits for many years. When they offer low interest rates or even no interest on at call balances, and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cash rate is presently 3.6%, they are effectively charging customers that differential in fees to hold their money. Almost all of this is margin given the low costs associated with maintaining these accounts for the banks. Most of the “savings accounts” with the major four banks have considerable terms and conditions attached to them that result in clients failing to meet the requirements to receive the savings rate offered. Even most of the term deposit rates available at the time of writing were below the RBA cash rate, despite such accounts locking up your money for a period of time. Offering such low rates on cash balances has certainly resulted in higher net interest margins than would otherwise be the case. But it has left the major banks vulnerable to a more nimble player with a lower cost structure offering savers a better rate. This is particularly the case in an electronic world, where accounts can be established easily online, with no requirement for an in-person interaction.

A Macquarie savings account can be established online in a matter of minutes. This has no doubt fuelled the acceleration in the flow of deposits towards Macquarie in recent periods. Most customers no longer use the branch network for any part of their banking business. Few have relationships with individual bankers. Most of those who borrow get advice from a mortgage broker, someone who is at arm’s length from any specific financial institution. Consumers are also more financially aware, with comparison sites highlighting superior offers on both the lending and deposit side.

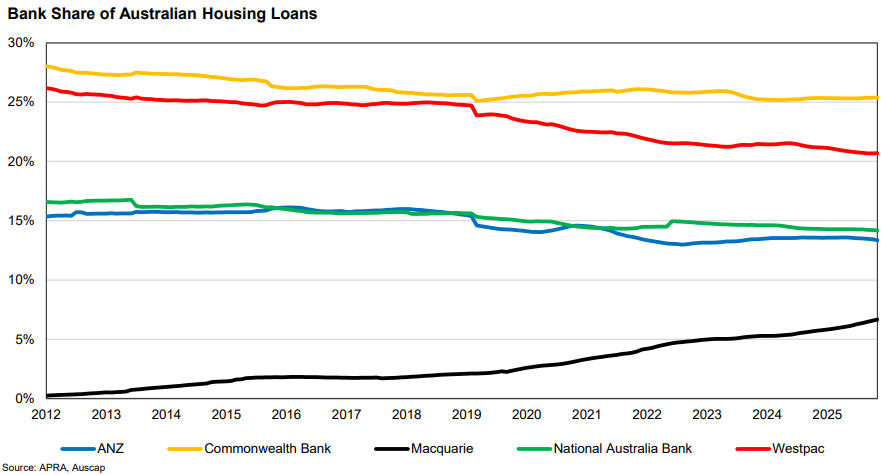

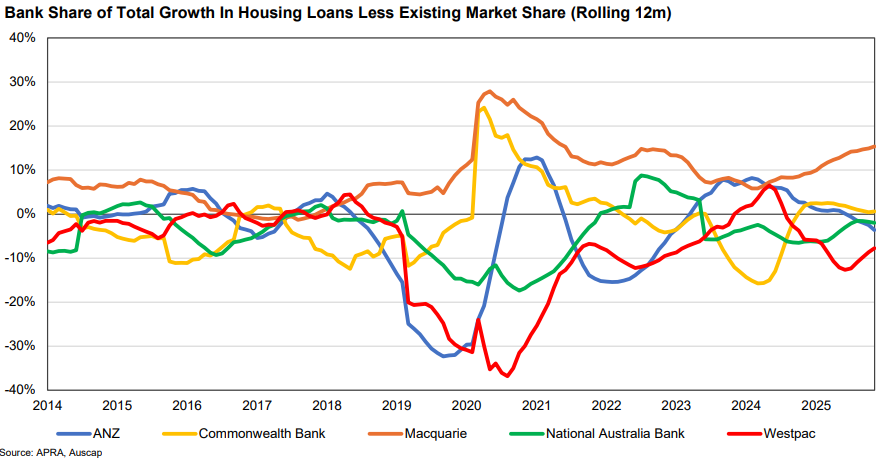

As can be seen in the mortgage share chart below, Macquarie has become a formidable competitor in recent years, a trend we expect will continue. Today the combined market share of the four large retail banks sits at 73.6% of the domestic mortgage market, but this is down 10% in the last decade. Macquarie is quickly becoming a relevant player.

Macquarie is almost exclusively focused on the retail broker channel for its mortgage lending. More than 95% of the home loans Macquarie wrote in the last half year were originated via the broker channel. Macquarie is winning in this channel by offering the two things the mortgage broker cares most about, a competitive interest rate and market leading turnaround times. On the funding side, Macquarie is attracting deposits at a rapid rate by having a “no hoops, no catches” savings account offering for at-call deposits. At the time of writing Macquarie was offering a 4.25% rate on up to AUD$2 million. This is higher than nearly every publicly viewable term deposit rate offered by the major banks, let alone their at call accounts. It takes very little time to set up an account with multi-factor authentication for most customers. In the last year this resulted in an increase in deposits of nearly $40 billion, taking Macquarie’s total deposit book to $192.5 billion.

On a rolling 12 month basis, the chart above shows the difference between each bank’s share of the growth of the total Australian housing loan market and their existing market share. Macquarie has been the only bank to have consistently increased its market share since 2018, with a noticeable acceleration in the last year or so. Macquarie is benefitting from a modern technology stack that is more efficient than peers, a deliberate focus on simpler clients targeting lower loan-to-value ratio and owner-occupier lending tiers, and the absence of the costs associated with having a legacy branch network. These advantages resulted in PBT margins for Macquarie’s Banking and Financial Services division of 45.1% in the 6 months to September 2025, up from 41% on the same period the prior year and approaching the average of its much larger peers. The operating leverage from this point should continue to be substantial. In the 12 months to 30 November 2025, Macquarie was responsible for 21.6% of the growth in the Australian mortgage market, taking its share of the aggregate mortgage market from 5.7% to 6.7%.

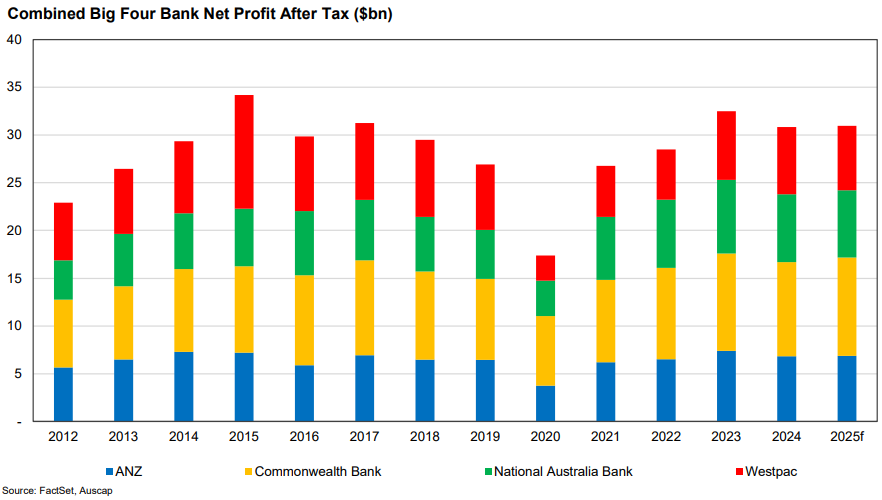

Macquarie is quickly gaining ground on ANZ and National Australia Bank’s market share. Assuming the market share of new loans for the 12 months ending 30 November 2025, Macquarie’s mortgage book would go past ANZ and National Australia Bank in market share within a decade. Of course a lot can happen in that time period, but the question is how the major banks will respond. It is difficult to see them taking a meaningful hit to profitability by changing their approach to at-call deposits, yet by capturing a greater share of deposits Macquarie is facilitating its growth in housing lending. Similarly, it would appear difficult for the major banks to immediately respond to Macquarie’s focus on improving turnaround times for mortgage brokers. It most likely requires meaningful investment in systems and technology. Given the earnings leverage Macquarie is gaining from increasing the size of its mortgage book, it seems likely that it will continue to compete aggressively in this space. Banking and Financial Services made up 20.9% of Macquarie’s net profit at the most recent result, having grown 22% on the same half a year earlier. No doubt Macquarie is eyeing the circa $30 billion in net profit after tax the big four banks make per annum.

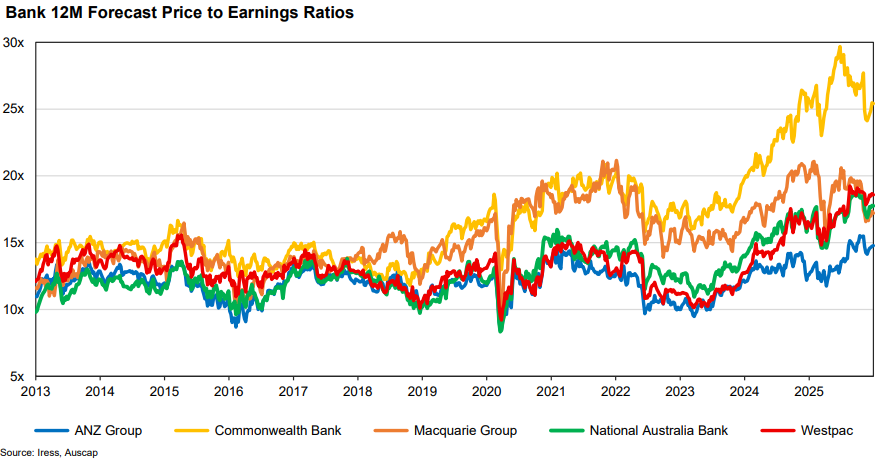

We acknowledge that Macquarie’s business mix is very different to the major banks and some of its divisions have been facing headwinds recently. That said, it is interesting to note that, at a time when Macquarie is actively competing head-to-head with the major retail banks and presently winning considerable market share, Macquarie is trading on a lower one year forward price to earnings ratio than three of the four retail banks, which has not historically been the case.

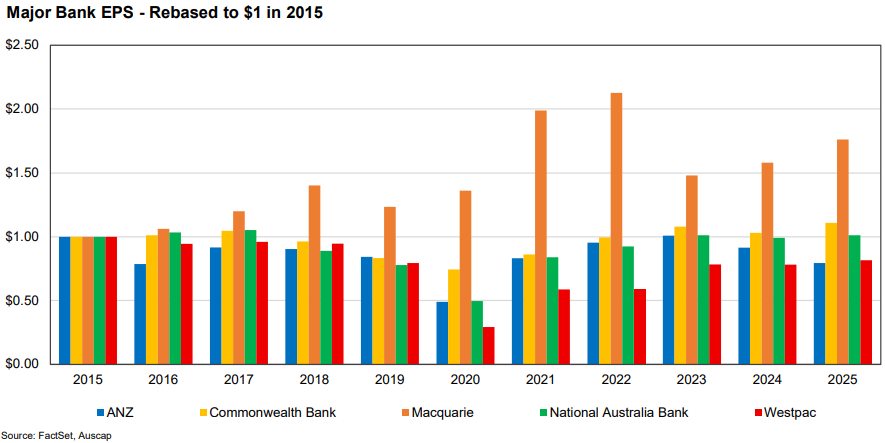

Over time Macquarie has demonstrated superior earnings growth, as the chart below highlights, and has had a higher average historic return on equity, averaging 13.8% over the last decade compared to 13.1% for Commonwealth Bank, 9.5% for ANZ, 10.7% for National Australia Bank and 9.8% for Westpac.

Auscap continues to hold Macquarie Group, which has been a long-term investment, in our high conviction strategy. We are cognisant of the widespread exposure that Australian retail investors and superannuation funds have to the major retail banks. We suspect this period of renewed investment and direct competition carries earnings risk. This is occurring at a time when bank valuations are extremely elevated. We continue to focus on investments in high quality businesses priced attractively that are likely to deliver an attractive return driven by dividends and earnings growth.

Tim Carleton is the Chief Investment Officer and founder of Auscap Asset Management. This article is an extract from Auscap’s January 2026 letter to investors. You can see a full version of the letter here. This article contains information that is general in nature. It does not take into account the objectives, financial situation or needs of any particular person.