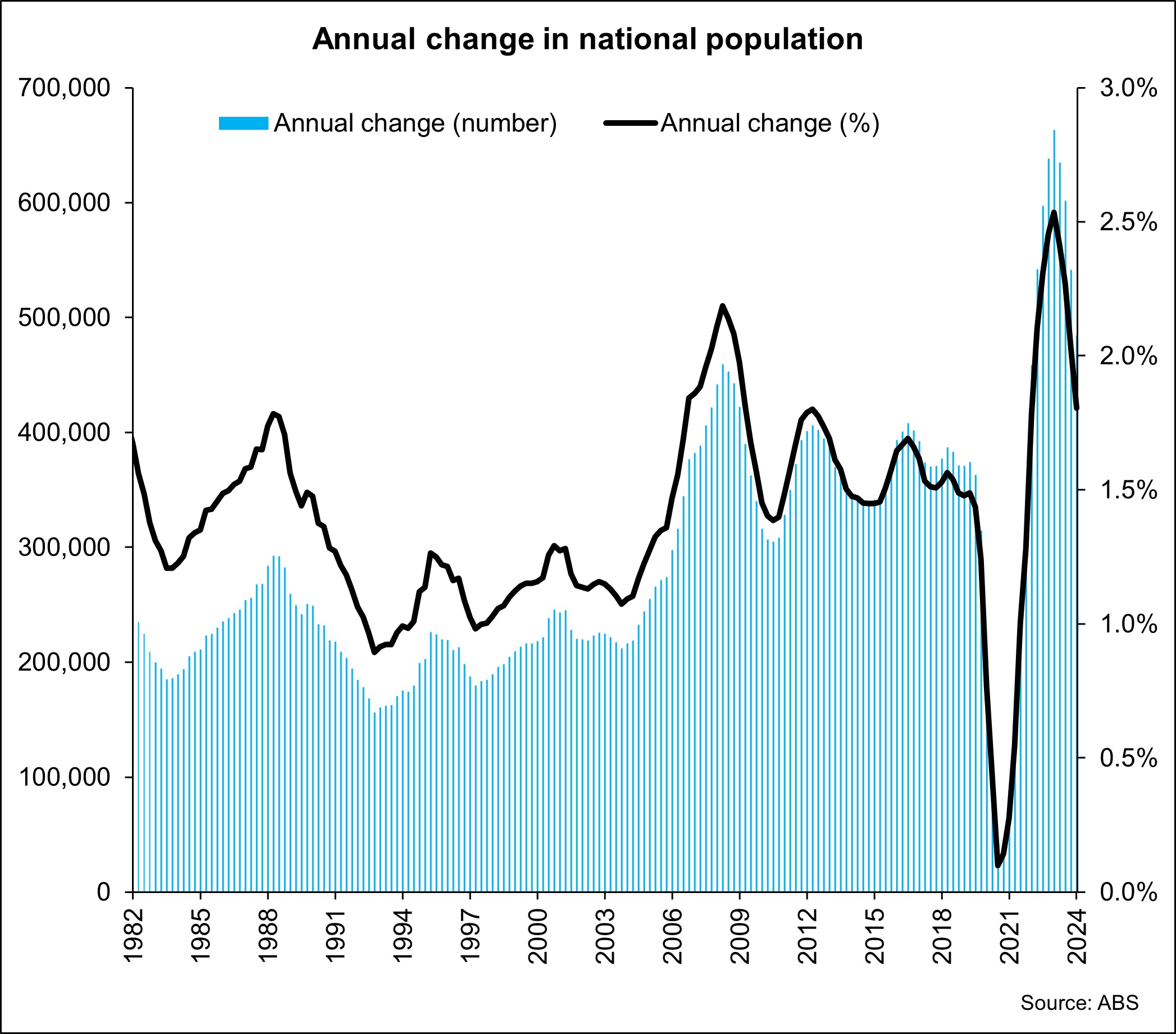

Since the international borders re-opened at the start of 2022, Australia’s population has increased by an estimated 1,538,039 persons, of which 1,244,138 came from net overseas migration (80.9%) and 293,901 came from natural increase (19.1%).

As the chart below highlights, Australia’s estimated population increased of 663,218 persons or 2.5% over the year to the peak in September 2023 were far in excess of previous highs.

The arguments for migration are that migrants add to demand and grow the economy. Further to this, someone doing the same work in a less advanced economy will be better off doing it in a more advanced one. Another argument is that we have an ageing population. Attracting younger migrants grows the taxpayer base and supports the ageing population, although this seems like a zero-sum game as those migrants age and you have to rinse and repeat.

So there are some strong and well-founded benefits to immigration. However, if we look at what the outcomes have actually been over the past three years we see:

- Slow economic growth with more than two years of falling GDP per capita.

- An ongoing slide in GDP per hour worked (productivity)

- The largest reduction in household incomes per capita on-record

- A large surge in nominal property prices

- A surge in nominal rental costs

- Low levels of new housing construction.

The main positive that has persisted throughout the surge in population has been a low unemployment rate, however, this has not translated into a significant increase in household incomes. This is why there now appears to be such a backlash against immigration. I don’t believe it is immigrants themselves that people see as the problem. It is the lack of planning for that immigration and the knock-on effect it has on everyone else.

Population growth, inelastic housing supply and rents

Housing supply is inelastic, meaning that significant changes in the rate of population growth such as those seen over recent years don’t necessarily result in a supply response.

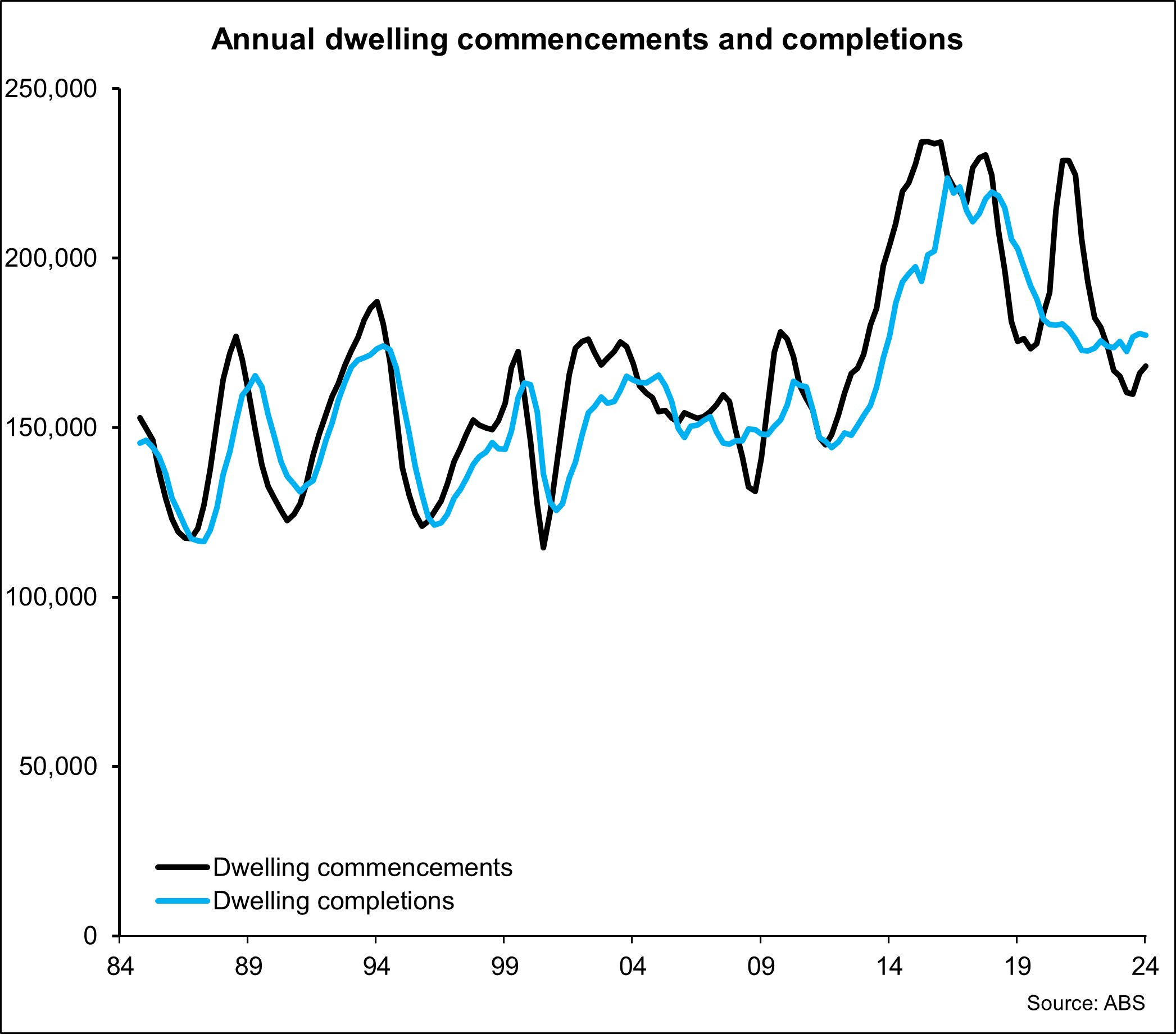

Over the 12 months to December 2024 there were 168,049 dwelling commencements. This was +1.8% compared to the 12 months to December 2023 but -28.3% compared to the historic high and well below the volume of commencements seen during the mid to late 2010s.

Similarly, the 177,313 dwelling completions nationally over the 12 months to December 2024 was +1.1% compared to the previous 12 months but -20.7% from the peak and, again, well below completion volumes achieved from the mid to late 2010s.

Since the reopening of the international borders we have not been building anywhere near enough new homes.

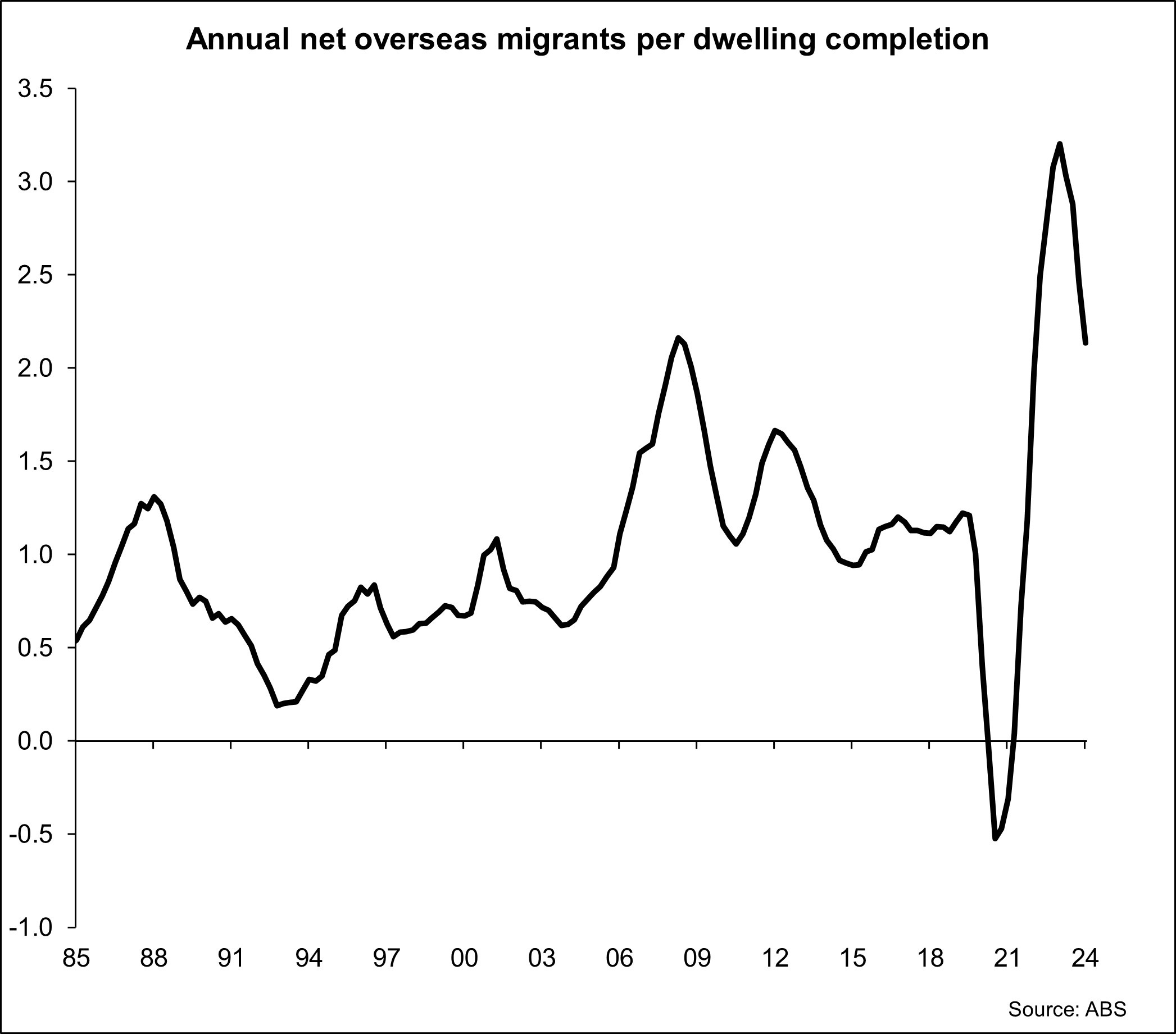

From September 1995 to September 2024, Australia has on average completed one additional property for every one net overseas migrant. Over the 12 months to September 2024, we’ve bult one new property for every 2.1 net overseas migrants, and that was as high as one home for every 3.2 overseas migrants in September 2023.

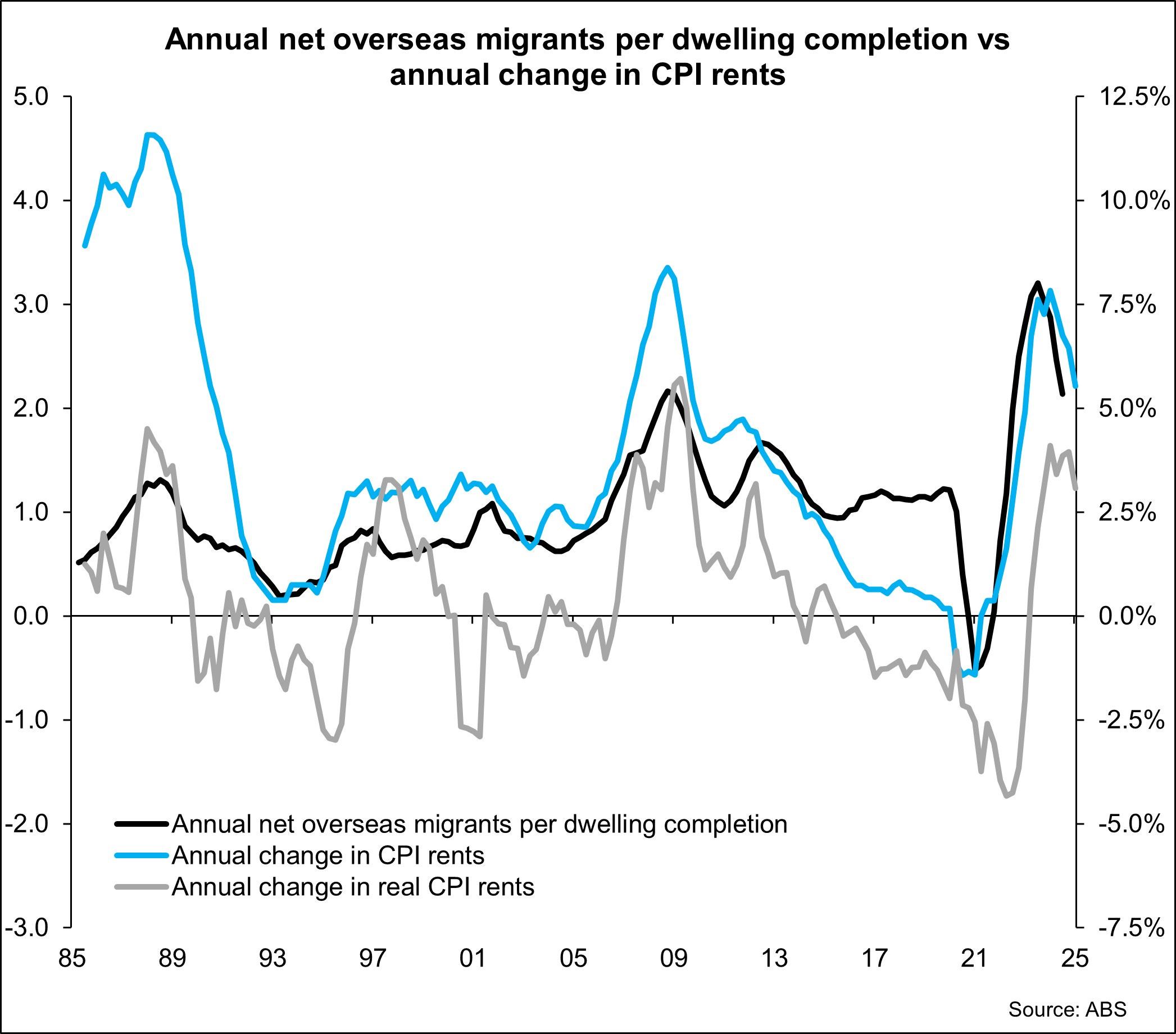

Except for a period in 2015 and when our international borders were closed, we have not built at a rate of one additional property for every additional net overseas since around 2007. We went quite close in the period from 2014 to 2019, a time that coincided with relatively moderate increases in rental costs (see chart below).

Fast forward to the last few years, and population growth and migration levels surged to record-highs. But because of the inelastic nature of the supply response, we have not built anywhere near enough new homes to cater to it. This has pushed the cost of renting significantly higher, both in nominal and inflation-adjusted terms.

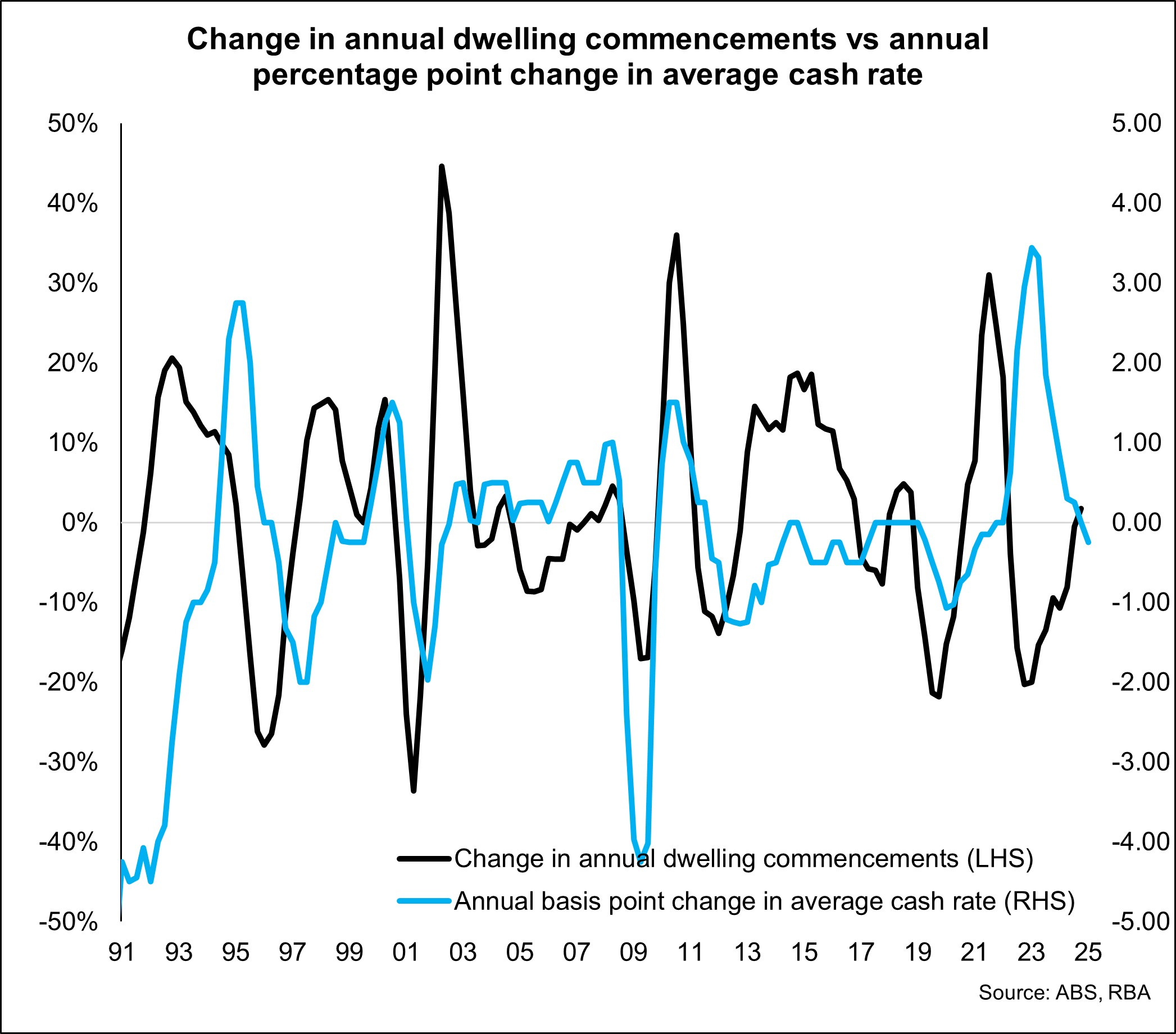

There are several reasons why supply hasn’t been able to respond. One of which has been the fact that interest rates were increased rapidly and ended up at their highest level in 12 years.

The above chart shows that dwelling commencements are highly sensitive to interest rates. In periods when interest rates have risen or fallen rapidly, there has historically been a fairly rapid response in the number of commencements. If we again look at the period from 2014 to 2019 when we were building a lot of new dwellings, interest rates were low, fairly stable and only reduced over that period. This made new housing construction much more feasible.

What is encouraging going forward is that the interest rate cycle looks to have peaked. As interest rates fall, more new housing projects should become feasible. The early recovery in housing construction we’re seeing should continue and could even accelerate.

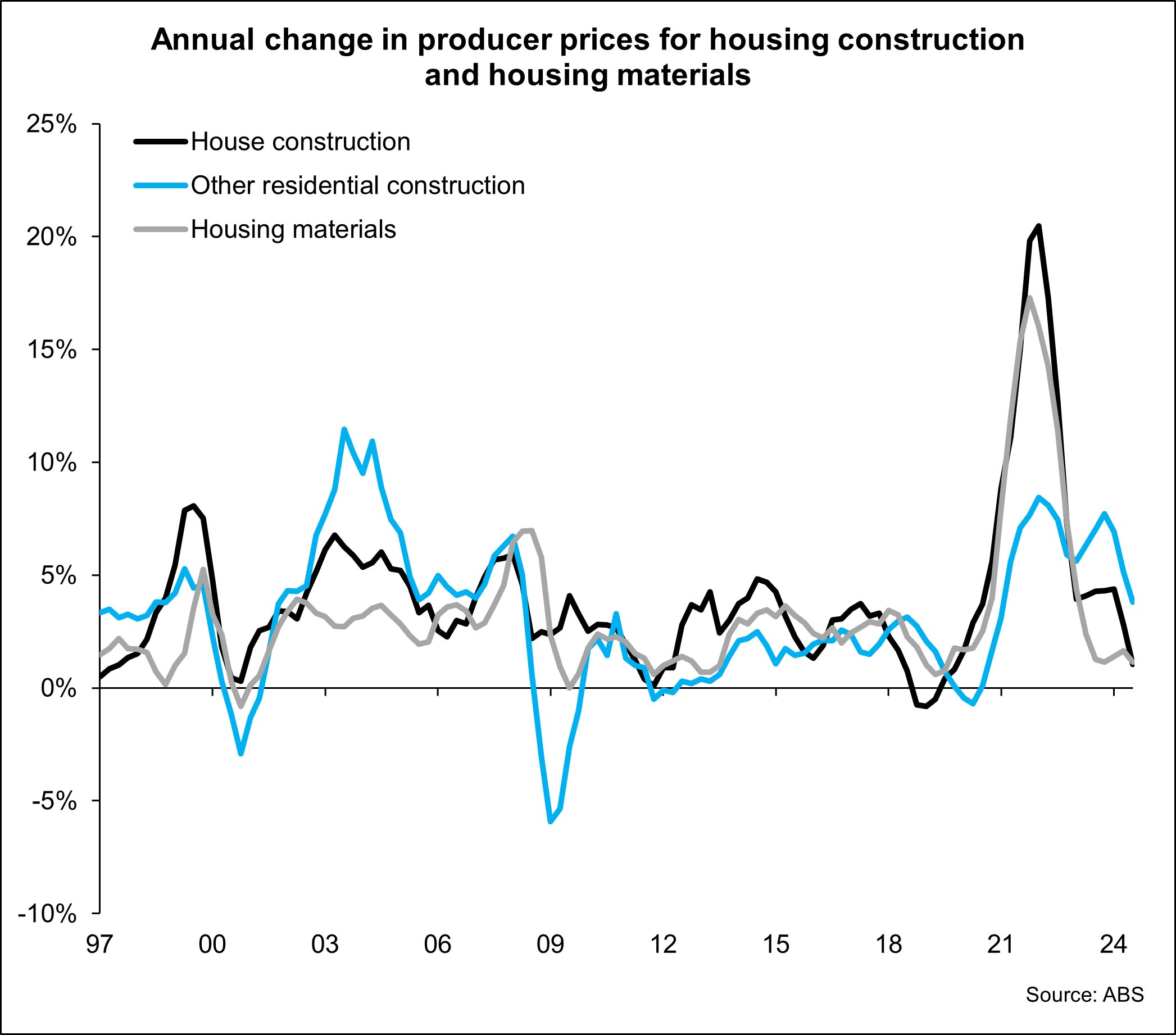

Another major contributor to the lack of housing supply response over recent years has been the rapid increase in the cost of housing construction. Producer Price Index data shows that the escalation in producer costs relating to construction have slowed however, they have risen substantially throughout the pandemic.

While housing construction costs are just 1.1% higher over the 12 months to March 2025, they were 41.6% higher over a five year period. Other residential construction costs are +3.8% over the past year and +28% over the past five years, while housing material costs are +1.1% over the past year and +34.9% over the past five years.

These significant increases in construction costs have made the premium for new housing significant compared to existing homes prices. They have also made much less new housing construction viable. By comparison, in the 2010s these costs were rising at a much more moderate and stable rate each year.

The recent moderation in these construction cost increases is positive for new supply. Yet in cities like Sydney and Melbourne, where housing is most needed and population growth is strongest, established price rises have been fairly moderate. As the gap between new and existing house prices is still quite wide, presales remain a challenge.

We need a population plan that is linked to housing

The inelastic nature of housing supply is the crux of the issue. We should have a population policy and why it should be linked to our ability to deliver both the housing to cater to that population growth the infrastructure required to cater to that population growth and the job opportunities to cater to that population growth.

If we want to have a high rate of population growth and migration, I believe we need to answer a lot more questions than we currently do and form a plan to link this growth to housing, infrastructure and employment policy. Some of these specific questions include but aren’t limited to:

- How many homes do we need for these migrants, who is going to build these homes and where are they going to be located?

- Is it sustainable for most migrants into the country to continue to settle in Sydney and Melbourne?

- If universities are reliant on overseas students for their funding, is this the right model and why don’t they use their land to build a lot more housing for these students?

- What infrastructure do we need to cater to this population growth, which is the top priority infrastructure and who is going to build it?

- What jobs are these migrants going to do?

- What is the impact of the increase in population on the current population of the country and how can we ensure their quality of life is not reduced from the migration occurring?

I know this is a very sensitive topic. I am married to a migrant and my father’s parents were both migrants. I wouldn’t be here and I wouldn’t have my family without migration, and Australia has been built on the back of it.

But as we are under investing in housing and infrastructure while running world-leading rates of population growth, I think it is reasonable to ask why we don’t have population plans linked to the delivery of housing, infrastructure and employment opportunities.

Cameron Kusher is Director at Kusher Consulting. He has more than 20 years' experience in the Australian property sector and regular shares his views on Oz Property Insights, from which this article has been republished, with permission.