I find it ironic that the fixed interest risk that most people fear is market risk. The fact that when yields go up, bond prices fall seems to scare many investors.

It shouldn’t.

The risk that bond investors should be most concerned about is credit risk. Only a credit failure can result in the permanent loss of capital and, potentially, a significant negative hit to a portfolio’s total return.

Market risk does not produce a permanent loss of capital. When yields rise there is an initial fall in the mark to market capital value of bonds, but higher yields result in increasing returns over time. I’ve written about this over the years (including in past articles in Cuffelinks), so I won’t become sidetracked by it again now.

Rather, this article discusses what credit risk and credit ratings are. In part 2, I will turn to the question of how credit risk can be managed so that it doesn’t wipe you out.[1] The good news is that, although credit risk is the more serious investment risk in my view, it can also be managed so that the risks are well worth taking.

What is credit risk?

The credit quality of a borrower is the likelihood that they will fail to honour their obligations to make timely payment of interest and principal. The world is an uncertain place and no bond issuer – be they a company or a government – has a 100% guarantee of never failing to pay.

There are a lot of factors that determine a bond issuer’s credit quality. There are financial factors, such as the amount of leverage an issuer has on its balance sheet. Issuers with low leverage have a stronger capacity to meet their debt obligations than highly leveraged issuers with low interest cover ratios.

The management strategy of the issuer is important. For example, strong risk management policies reduce credit risk, as does a clear and robust governance framework.

Finally, the industry in which a business operates is an influence on credit quality. Some industries are relatively stable, while others are volatile; some have a small number of well-established participants, while others are much more open to new start-ups taking market share from existing players.

What are credit ratings?

One of the most commonly used tools in credit risk analysis is credit ratings. Most people have heard of ratings, even if only when our politicians talk proudly of how the government still has a ‘triple A’ rating.

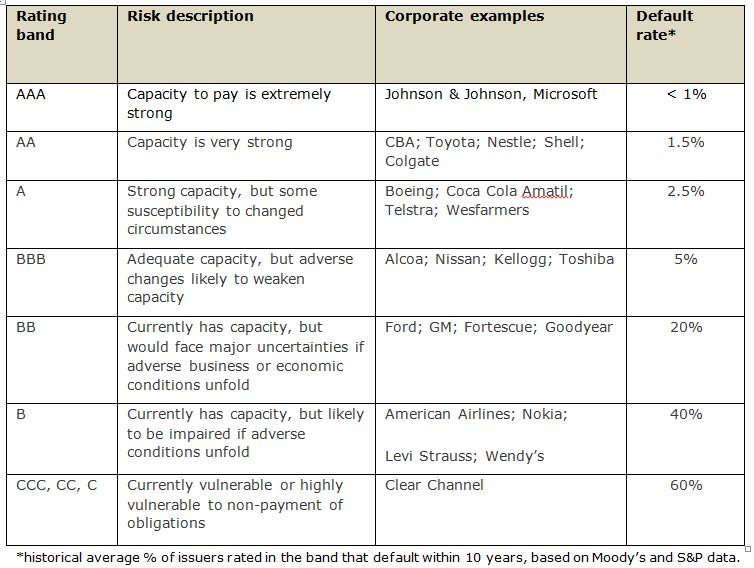

There are many different ratings scales that can be used, but the table below provides an overview of the ratings framework used by most agencies and credit analysts. In this framework, AAA ratings are assigned to borrowers with an ‘extremely strong’ capacity to pay. As the capacity diminishes the rating moves to AA, then A, then into the B’s.

It’s important to understand that credit ratings are subjective opinions about an issuer’s credit quality. They are an analyst’s view, after considering the sort of factors mentioned above, of the issuer. Different analysts can have different views and there is no absolute right or wrong rating.

Also, ratings aren’t set in stone. As economic and business conditions unfold, some issuers improve and may receive a credit upgrade, while others deteriorate and may be downgraded. In recent years, Wesfarmers has moved from BBB to AA, while Nokia has been downgraded from BB to B.

As a guide to the likelihood of default, ratings are more of a relative guide than an absolute probability. For one thing, the average default rates shown in the table above mask a great degree of variance year to year. Years like 2008 and 2009 saw above average defaults across the spectrum of ratings, while in many years there are very few.

What are credit ratings not?

Finally, ratings are not an indication of the probability of losing capital if there is a default. Some debt investments have a high probability of default, but are secured against tangible and liquid assets that can be sold so that investors recover some of their capital. Others have a strong credit risk rating, but if a default occurs the recovery rate may be quite low.

It’s also important to appreciate one thing they are not. Ratings are not investment recommendations. They are an input, but don’t provide sufficient information to make a decision about whether to invest or not. This works both ways. AAA rated bonds are safe, but may be poor investments if they are paying a very low yield or if the recovery rate if there is a default is very low. On the other hand, while the credit risk of BB and B rated bonds (sometimes unhelpfully called ‘junk bonds’) is high, they are often excellent investments because of their high yields and reasonable recovery rates if there is a default.

The returns you make from investing in fixed interest are a combination of the interest you receive and capital losses from defaults. A high-yielding portfolio may provide an investor with as much as 3 or 4% above low risk portfolios like cash or term deposits. But if you experience a default or two you can easily lose more than 3 or 4%. This can wipe out the extra income you had hoped to receive.

Part 2 will address strategies for managing credit risk effectively.

Warren Bird was Co-Head of Global Fixed Interest and Credit at Colonial First State Global Asset Management until February 2013. His roles now include consulting, serving as an External Member of the GESB Board Investment Committee and writing on fixed interest, including for KangaNews.

[1] Recommended reading for those interested in delving deeper includes the fulsome information provided by Standard & Poor’s on their website, http://www.understandingratings.com/ or the overview found at the Australia Ratings’ website http://australiaratings.com/corporateratingmethodology