The past few months have exacerbated a trend we have been following with concern for some time now – the ever-increasing disconnect between financial markets and the real economy.

The COVID-19 outbreak has triggered a huge expansion of government balance sheets which in turn has enabled market darlings to reach dizzying valuation heights, to the point where financial markets might best be described as Ponzi borrowing.

This type of financial instability is not new, but when combined with the impact of a health crisis, it is particularly troubling.

Financial instability moves

Distinguished economist Hyman Minsky developed the financial instability hypothesis in the 1970s, which argued that capitalism moves between periods of financial stability to instability, with periods of stability leading to overconfidence by borrowers and lenders and encouraging excessive borrowing. This in turn increases volatility and ultimately triggers a crisis.

At the moment, Minsky’s hypothesis seems particularly relevant. The proportion of zombie companies (companies that are able to service, but not pay off, their debt) is growing, while productivity is declining, and economic growth is illusory. And if significant proportions of lending are based exclusively on an expectation of rising asset values, the result is Ponzi finance.

Worryingly, this trend shows no sign of having peaked. Indeed, the significant and long-term implications of COVID-19, and the decisive steps taken by governments and central banks around the world in response, have accelerated the pressure on stability.

At the same time, it has justified extraordinary monetary and fiscal stimulus actions that would usually be seen as overstepping mandates, and the scale of this overstepping will only increase as the system becomes increasingly unstable.

But having cried wolf too often, no-one now takes seriously the prospect of central bank balance sheet reduction or an end to monetary support.

Valuation-based investment

The disconnect between the financial system and the real economy has seen many investors lose faith in the concept of mean reversion and the strategy of valuation-based investment. Instead, the rewards seem to have flowed to those who seek ‘quality’ and ‘growth’, though perceptions of ‘quality’ seem to exhibit a high degree of subjectivity. In some ways, it can be described as chasing high multiples for market darlings and loss-making businesses that are supported by government largesse.

Exacerbating this trend is the recent growth in index investing which has constantly rewarded share price winners and punished losers without regard to fundamentals.

At Schroders, we continue to subscribe to the belief that mean reversion (at some point), and investment in real economy businesses which have not been inflated by easy money, will be rewarded, although there is no doubt that following this investment approach now has been tougher than ever.

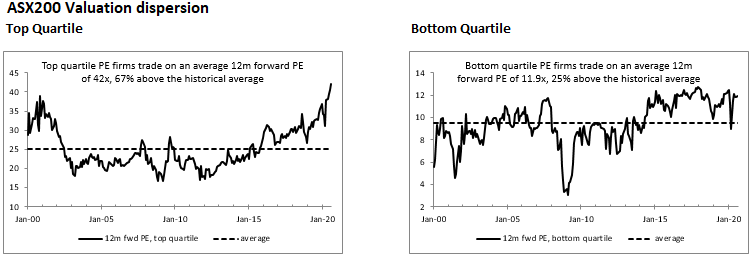

Nonetheless, to us it seems inarguable that growth is an input to be used when valuing a business, not just an attribute to be sought at any price. On this basis, valuations of companies predicted to have attractive growth prospects have escalated far beyond realistic levels. As shown below, the top quartile Price/Earning (P/E) companies in the ASX200 have a P/E of 42 versus only 12 for the bottom quartile, a remarkable value dispersion for Australia's top companies.

Perhaps even more worrying, they have maintained these valuations even as markets start to cool down.

Despite the fact that the global economy is presenting few growth prospects, we are seeing profit forecasts that would be unconvincing in a booming economy, let alone one that is being hit hard by a global pandemic.

Global financial casino

We continue to believe that fundamental value creation happens slowly, and that our role is to protect our investors’ hard-earned capital against the excesses of global financial markets – or perhaps what we could call the global financial casino. We remind investors that history has shown, time and again, that all bubbles burst and that growth cannot continue into perpetuity.

At the same time, we acknowledge that there will be no rapid exit from the global financial casino.

It seems more than likely that the current policies aimed at supporting the supremacy of the financial system over the real economy will continue, with a global financial casino running alongside a real economy that is increasingly fuelled by debt-funded government support.

For investors, the challenge is to identify which investment strategy is best suited to this environment.

On one hand, investors could simply abandon any realistic attempts to value companies and instead simply chase the hot streaks. But this type of herd behaviour is not ‘investment’. The share price alone is creating the appeal, not underlying value creation.

Another option is to rely on considered and realistic views of valuation, grounded in the low-growth and high-risk environment investors face. But to take this approach, investors must accept that fundamental value creation happens slowly and does not result in 200% share price gains in a quarter.

In a year when ‘social distancing’ has entered the lexicon, we continue to believe that staying away from the herd, by chasing growth with nothing to support it, is still the best path to take.

Martin Conlon is Head of Australian Equities at Schroders. This article contains general information only and does not take into account your personal objectives, financial situation or needs. These matters should be considered before acting on the information provided.