Interest rates can be viewed in either of two ways: in nominal or real terms.

It’s the nominal interest rates (or nominal yields) paid on deposits and bonds that determine the cash returns investors receive from their interest-bearing investments. And it’s nominal interest rates that determine how much borrowers pay on their debts. Current examples of nominal rates in Australia include 3.9% on a two year term deposit and 3.6% on a ten year government bond.

Nominal interest rates are important for another reason: changes in them are the main influence on the market prices of bonds (bond prices move inversely with nominal yields) and other financial assets traded on financial markets.

Real interest rates (or real yields) are nominal rates adjusted for inflation. A real interest rate is usually calculated by taking the relevant nominal interest rate and deducting the inflation rate recorded over the preceding 12 months.

An alternative is to calculate an expected real interest rate – by taking the relevant nominal interest rate and subtracting the expected rate of inflation. The problem is we don’t have good measures of expected inflation.

Think in real terms

Real interest rates are important. They measure the percentage return from an investment in terms of what it does to the purchasing power of the investor – and they also show how the percentage cost of paying interest on a loan in terms of the purchasing power of the borrower.

Real interest rates are also a useful guide to whether monetary policy is easy or tight. For example, low (or negative) real interest rates suggest that monetary policy is accommodative or stimulatory; high real interest rates suggest that monetary policy is tight.

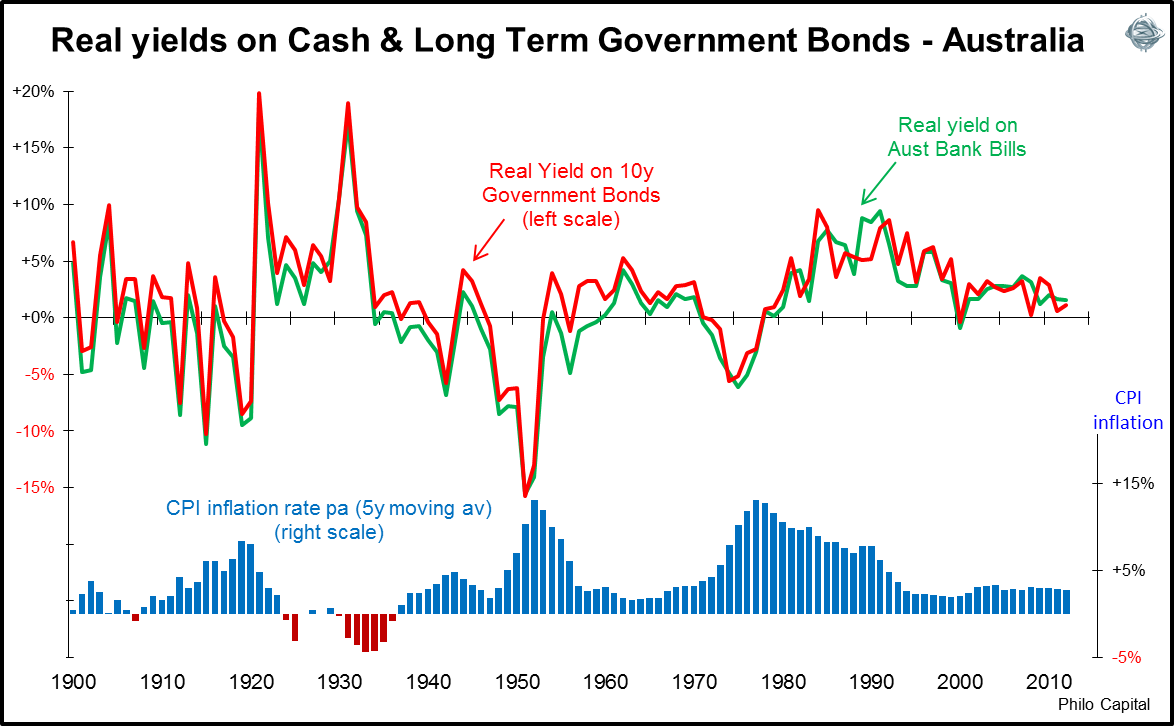

The chart shows the history of two important real interest rates in Australia, those on three month bank bills and ten year government bonds. These real rates, which fluctuate widely over time, are affected by moves in nominal interest rates and by inflation. Real interest rates have generally been high when inflation was falling (1920s, 1930s and 1990s) and low or negative when inflation was rising (early 1950s, 1970s).

Since 1990, Australian real rates have trended markedly lower – that’s because nominal interest rates have declined by more than inflation. Some real interest rates have fallen from over 8% – how good was that for savers but how tough on borrowers! - to less than 1.5%.

Around the world, real interest rates are now unusually low or even negative. That’s the aim of the policies of the major central banks, with the exception of China. The US central bank has kept its nominal cash rate close to zero for almost five years and frequently reiterated its ‘forward guidance’ that it will maintain the ultra-low cash rate ‘for an extended period’; it’s been buying US bonds at the rate of US$1 trillion a year and expects to ‘taper’ that programme only as the economy gains strength; and via ‘operation twist’, it is lowering long-term real yields by purchasing long-dated bonds and selling bonds with shorter-dated maturities.

My guess is that the central banks of the US, Japan and Europe will continue to maintain real yields at quite low levels - often accepting negative ones - as they try to nurture their economic recoveries. (Yes, even Europe now has some ‘green shoots’ of recovery).

Hunt for real yield a preoccupation

This means the hunt for real yield that’s become a preoccupation of investors both here and abroad is likely to remain a dominant feature of investment markets for several years at least.

People with savings will need to continue to seek out the higher real yields that quality corporate bonds can offer relative to the low real yields available on government bonds. Savers should also be prepared to ‘shop around’ for the best deals on term deposits and at-call deposits to ensure they are getting the best possible real returns on these assets. And shares paying good and growing dividends – especially those carrying franking credits – will have enhanced appeal to investors keen to earn an attractive rate of real returns.

Anyone thinking about what might happen to real interest rates over the medium-term and beyond may have to allow for what might be another powerful influence keeping real interest rates at low and at times negative levels.

Governments and central banks in debt-laden countries seem likely to be more tolerant of inflation than they’ve been in recent decades. As Pictet Asset Management observed recently,

“Policy makers in advanced countries are not the strict disciplinarians they once were … Higher inflation and negative real interest rates present heavily-indebted countries with a less disruptive way to reduce the real value of government debt compared with alternatives such as sovereign default or deep spending cuts.”

In the early years after the Second World War and again in the 1970s, governments of many industrialised countries, including Australia, tolerated inflation and negative real interest rates to reduce the huge increase in the real value of the government debt they’d issued and the interest costs of servicing those swollen borrowings. Investors holding deposits and bonds suffered badly, as the graph reminds us.

Recently, Japan has adopted a policy of ‘let’s have inflation’. If the US and Europe, both of which also have much-increased levels of public debt, follow this lead, investors around the world might have to cope with rising inflation and low or negative real interest rates in the medium term. That would be a worry for investors – particularly self-funded retirees.

Don Stammer is former Director, Investment Strategy at Deutsche Bank Australia and is currently an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund, Altius Asset Management and Philo Capital. The views expressed are his alone.