As a holder of bank hybrids in my super fund, I have recently been pondering the APRA-confirmed phasing out of ASX-listed bank hybrid securities from January 2027. This follows APRA and ASIC concerns over complexity risk.

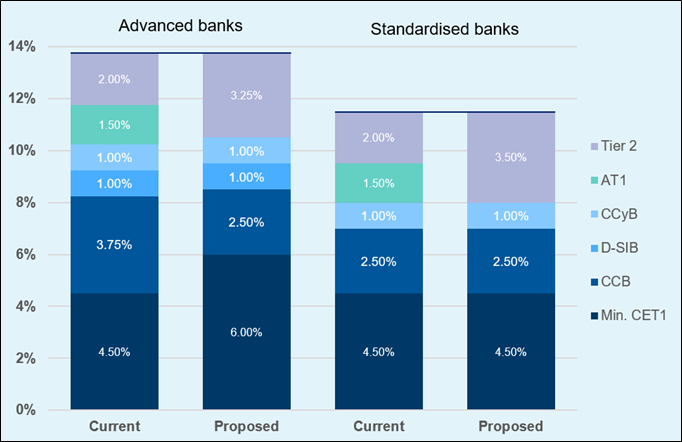

More technically, these are Additional Tier 1 (AT1) capital instruments, which together with Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1), consisting primarily of ordinary shares, makes up a bank’s total Tier 1 capital.

AT1 capital is perpetual but callable, can convert to equity, and income is not guaranteed. In a bank’s capital structure, it ranks above CET1. Next in the capital hierarchy is Tier 2 Capital, consisting of subordinated debt with defined maturity, no equity conversion trigger, but subject to loss after both CET1 and AT1 have been exhausted.

Figure 1: Current vs proposed capital stacks

Source: APRA

Actually, I have been winding down my own holdings ever since the 2023 Credit Suisse AT1 wipeout. And I must confess to an incomplete risk assessment of these instruments prior to that event. But first, a recap on hybrids.

The purpose of hybrids

The raison d’être of bank hybrids is not so much about raising funds as it is about providing risk absorbing capital. It is a structure designed to strengthen the capital adequacy of a balance sheet to absorb losses in a crisis.

In times of extreme stress, Australian bank hybrids are designed to protect deposit holders and help the bank to remain solvent without a government bailout. Specifically, these features include:

- if a bank’s CET1 capital ratio falls below a certain threshold, the hybrid converts to ordinary shares, usually at a discounted rate creating a capital loss.

- in the extreme, if conversion isn’t possible the hybrid can be written off entirely creating a 100% capital loss.

- crucially, APRA has the ability to declare a bank ‘non-viable’, causing conversion or write-off. A subjective and powerful trigger, this was the reality of the Credit Suisse crisis.

These loss-absorbing features position investors and not taxpayers to wear the losses of a bank crisis.

Many retail investors, however, are unaware of these features and don’t fully understand the risks. In fact, their eyes glaze over with the yields on offer, often fully franked, thinking they are safe, ASX-listed, regular income-like bonds, issued by major banks creating an illusion of security. When in fact in a crisis, they’re closer to equity that could be wiped out in a severe downturn, even before ordinary equity holdings.

The Credit Suisse episode

One could be forgiven for conducting one’s own risk assessment and quite reasonably concluding that banks are as safe as houses in this country. But the fact that APRA and ASIC have concerns suggests that that cannot be guaranteed. That what happened with the Credit Suisse AT1 write-off could happen here. Remote as it may seem.

Specifically, in March 2023, Switzerland’s second largest bank, Credit Suisse, suffered an almighty crisis of confidence following scandals, financial losses, and a run on deposits. At lightning speed to prevent collapse, Swiss regulators forced a merger with UBS, the largest Swiss banking institution.

What happened next shocked investors and markets. AT1 holdings of approximately US$17 billon were wiped out entirely and ahead of ordinary equity, even though it ranks above equity in the capital structure. Equity holdings were heavily discounted but not totally wiped out, with approximately US$3.25 billon returned. Senior debt remained intact.

This occurred because the Swiss regulator invoked a ’non-viability clause’, common in AT1 instruments, including Australian bank hybrids. The regulator said that, “the conditions for a write-down of AT1 capital instruments were met”, and that “a viability event has occurred”.

Lawsuits were threatened, but the upshot was that AT1 capital can be legally wiped out even if shareholders’ capital is not. And this is why APRA has moved. To avoid a Credit Suisse-style scenario, and to protect retail investors from these complex financial instruments, with many believing they just behave like bonds. Until suddenly they don’t.

What to do with hybrids now?

So, what now for those holding hybrids who want to maintain similar economic characteristics and risk profile in their portfolio? A synthetic hybrid position might be worth considering.

For example, create a proxy for a bank hybrid using a combination of bank and corporate debt, equities, and possibly bank derivatives and term deposits. That is, replicate as close as possible, the income and risk profile of a bank hybrid.

Specifically, replicate high, floating, and franked income with some credit and equity risk exposure, using ASX listed securities available to retail investors. That is, create something that sits between debt and equity, that behaves more like equity in a crisis, and is bond-like in normal times. The following is an attempt to build an AT1-like portfolio based on these characteristics.

- For an income stream, consider individual stocks yielding high franked income, and possibly writing covered out-of-the-money call options for extra income which also serves to limit any upside, reflecting a hybrid’s reduced capital growth potential. Alternatively, invest in an ETF like YMAX which implements a covered call strategy over a basket of ASX-listed large-cap industrials and financials, to enhance franked dividend income.

- For credit risk exposure, consider ETFs QPON, which tracks senior floating rate bonds issued by Australian banks, and BOND which includes government and corporate bonds, capturing some credit risk, albeit at the senior debt level rather than the subordinated level implicit in AT1s.

- For some equity risk exposure, invest directly in bank shares or an ETF such as MVB which provides exposure to ASX-listed banks and financial institutions. The loss absorption characteristic of bank hybrids cannot be perfectly mimicked but it could be approximated by keeping this portfolio weighting to a minimum in good times, with cash reserves at the ready to increase in times of market stress (the Buffet way: buy when everyone else is selling).

- And keep a cash buffer by holding for example, ETF cash proxies AAA (short term deposits) and BILL (short term securities or bank bills). And possibly include term deposits for some fixed income and capital stability. Cash holdings serve several purposes. As mentioned, it can be used to increase equity holdings. And as hybrids are less volatile than equity, having cash in a portfolio smooths that volatility. And finally, BILL mimics the bank bill rate implicit in the hybrid’s distribution rate.

Yes, there is overlap in the four investment buckets here, with for example equity exposure in buckets 1 and 3, while debt features in buckets 2 and 4. But deliberate separation helps maintain discipline and focus on the role of each, which combined aims to synthesise a hybrid-like portfolio.

The income and credit risk weightings might make up say 60% of the portfolio (say 30% each). With the equity risk and cash buffer the other 40%, commencing with a lower equity portion (say 10% equity, 30% cash buffer), increasing with market stress. Of course ultimate weightings would depend on an individual’s appetite for risk.

By no means the only portfolio that could attempt to replicate bank hybrid features, this one would reflect floating rate, franked income, with capped upside via covered calls, bank equity risk, credit risk, and lower overall volatility compared to pure equity. The income level should be comparable to bank hybrids, and back-testing could confirm that.

A synthetic hybrid strategy therefore may allow investors to achieve similar income and equity exposure, but with more control over risk. And in the meantime, for those investors with bank hybrids still in their portfolios, perhaps only hold on to as much as you’re willing to accept being wiped out.

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary.