What made the GameStop squeeze remarkable was its velocity and magnitude. Stock promoters used social media to communicate their message to spectacular effect. The evidence suggests most GameStop buyers acted on a conviction that they would profit by selling to a forced buyer after the crowd drove up the stock price.

There was limited evidence that these investors evaluated the fundamentals of the business. Boosted by social media and lubricated with fiscal and monetary stimulus, the collective power of the positive narrative overwhelmed the fundamental-based reasoning of the established short interest of hedge funds.

Social media spectacularly demonstrated a unique capacity to influence traders and violently move markets. The power of sentiment, unconstrained by fundamentals was amplified, and volatility reigned.

Why is this new source of volatility a big deal?

It is not difficult to imagine that easy money combined with social media’s power to promote a narrative will result in more situations like GameStop. Markets have become accustomed to central banks acting to limit downside volatility. It seems strange to consider that volatility on the upside might also upset markets, yet we just saw that happen.

Beyond the stories of sole traders making millions, the notable outcomes of the GameStop spike reported were:

1) heavy losses at respected hedge funds, resulting in portfolio rebalancing, liquidation and recapitalisation, and

2) online broker Robinhood’s expedited $3 billion equity raising to meet adjusted capital buffers and margin calls.

These outcomes are indicative of the broad and meaningful implications for markets should there be a re-evaluation of volatility, even if it is skewed to the upside. GameStop’s share price spike resulted in liquidations and margin calls. These are signals of stress we usually associate with bear markets, not rising markets.

Not simply a zero-sum game

The upside-skewed volatility burst also impacted long-short strategies. These strategies commonly access leverage by reinvesting the dollar proceeds of their short sales to add investments in their long exposures. Securities lending is essentially leverage.

If markets become more wary about unpredictable upside spikes in stocks, long-short strategies are likely to become more selective with their short positions thus generating less leverage to invest in their long positions. This deleveraging is likely to reduce market liquidity. To the extent that many of these strategies crowd the same themes and factors, it may also narrow the dispersion of valuations.

Greater volatility will also affect the activity of market makers and options traders. Options traders use volatility to determine premiums (prices). Generally, higher volatility makes options premiums more expensive. Underestimating volatility is dangerous for traders selling uncovered options. Uncovered means that the trader doesn’t own the underlying stock and is therefore exposed as a forced buyer in the event of a spike in the share price. A short option position has limited upside and unlimited downside. With this sort of payoff, you do not want to sell too cheap.

Options are generally sold by market makers with large, finely-tuned portfolios which are often leveraged and highly sensitive to sudden and violent changes. Market makers are an important contributor to market liquidity and provide valuable risk management tools. Dislocations for market makers can have broad market consequences, particularly for the counterparties who use markets for the purpose of insurance rather than speculation.

Effective markets need secure counterparties

The margin calls faced by Robinhood highlight the importance of the trading hubs upon which the integrity of financial markets depend. Much of the counterparty risk in financial markets is managed or intermediated through an exchange or a clearing house. For example, the owner of a call option relies on a clearing house to deliver on an ‘in the money’ (profitable) contract when that option is exercised. If the seller of that call option does not post sufficient margin to settle the trade, the clearing house wears the loss.

Volatile price movements can result in extraordinary margin calls (such as those demanded of Robinhood). If additional funding cannot be secured, margin calls will result in forced liquidation and can create market dislocations and elevated counterparty risks. Layers of leverage and opacity associated with stock lending and derivatives tangles the web of counterparties.

In a worst-case scenario, a sudden breakout in volatility could erode confidence in the market hubs and thus the integrity of markets.

We have grown to accept the central bank put

For decades, investors have become accustomed to central banks providing a backstop to markets to dampen volatility. The perception is that central banks have unlimited capacity to provide adequate liquidity to overcome any market dislocation. When a systemic risk to markets emerges, we no longer hope for a central bank bailout, we expect it.

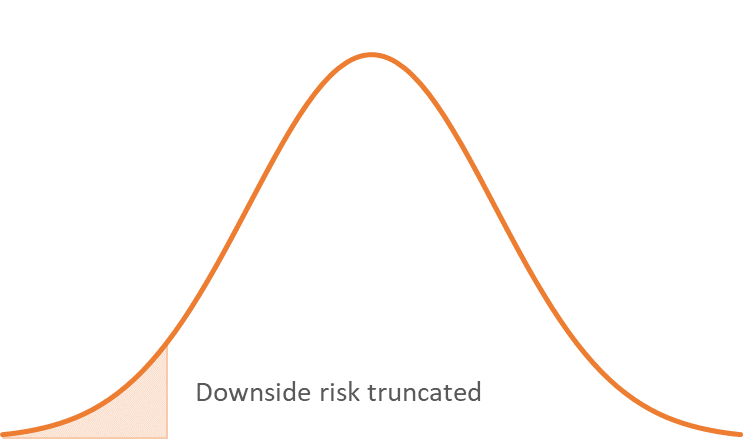

A contemporary view is that central banks should have an asymmetrical impact on markets. That is, they should support failing markets but do not need to act against speculative bubbles. An interpretation of this might be that central banks truncate downside tail risks and thus reduce overall volatility.

Graphically, this might look like the chart below.

Does the ‘Fed Put’ cut tail risks and limit volatility?

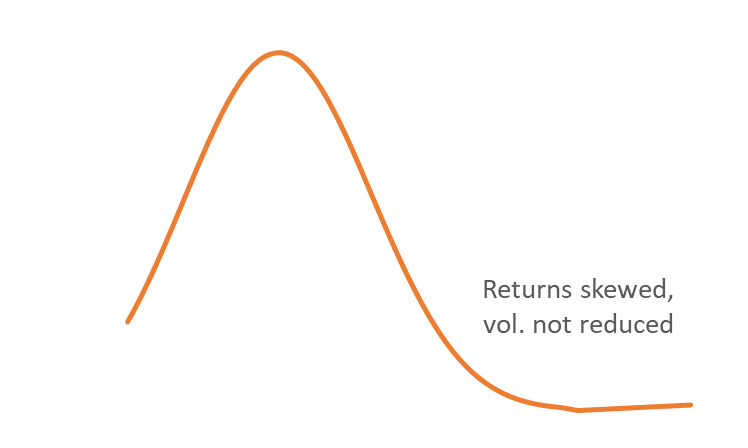

The GameStop saga could justify an alternative interpretation. Introducing asymmetry may skew the distribution of returns (to the upside) but not actually reduce volatility. If the impact of the ‘Fed Put’ is to skew returns as displayed in the below graph, volatility is not reduced, merely altered.

…Or does it just create more skew, with no reduction in volatility

GameStop demonstrates a paradox. Did this happen because easy money actually contributed to a breakout in volatility?

If that is the case, further central bank actions might only exacerbate volatility and have the converse effect of reducing liquidity and risk appetite.

The implication for Australian small companies

This has implications for small companies in Australia.

The most direct and obvious is that it elevates the risks for short interest. A share price spike created by a social media-led buying frenzy may be short lived; however, margin calls and leverage mean even brief spikes can lead to forced liquidation and significant losses. Contemporary hedging strategies for example, those used to reduce exposure to market risk or ‘beta’, might need fine tuning.

A debate about the appropriate estimate of volatility may also impact the valuation gap between market favourites and less sought-after names. A feature of Australian small companies in recent years has been the increased dispersion of valuations between companies. Market realities and themes such as lower interest rates and growth scarcity explain most of this; however, it has also been exacerbated by long-short strategies. An unwinding of these positions may reduce this dispersion.

If volatility has been underestimated, it is indicative of a mispricing of risk across the market. Perhaps central bank bailouts have not reduced volatility by simply truncating the downside. Maybe they skew the distribution into a fatter tail on the upside, with less reduction in volatility than previously thought.

The best performing stocks are generally companies which are sustainably building valuable businesses. However, if volatility has been mispriced as described, the best opportunities are likely to arise from contrarian viewpoints rather than pursuit of expensive momentum.

Sinclair Currie is a Principal and Co-Portfolio Manager at NovaPort Capital, a boutique Australian equities investment manager specialising in small and microcap ASX-listed companies. This article is for general information only and does not consider the circumstances of any individual.