The RBA’s Quantitative Easing (QE) bond-buying program during the pandemic saw its balance sheet expand to more than $600 billion, creating accounting headaches in the process. It’s now trending back towards its pre-pandemic level of about $150 billion, currently sitting at a more reasonable $400 billion.

The reduction is occurring as the RBA allows its bond holdings to run-off the balance sheet as they mature. This process is known as ‘passive’ Quantitative Tightening (QT), as opposed to ‘active’ QT which sells bonds back into the market. Both forms of QT reverse QE.

QT is contractionary, yet unfolds at a time when the RBA is cutting interest rates, which is expansionary. So why the contradiction? Before answering the question, we first consider the mechanics of QE and QT.

Some quick housekeeping.

- Bank reserves (Exchange Settlement balances), are commercial bank deposits held at the RBA, used to settle interbank payments. They form part of the monetary base, or ‘base money’, as measured by M0.

- Money held by the public in the form of currency and deposits is captured by the measure M1, while ‘broad money’ (M3) includes M1.

- Commercial banks act as intermediaries between the RBA and the private sector, while the RBA handles government transactions.

Understanding government borrowing

Let’s begin at the beginning, with the government borrowing money. It does this by issuing bonds. Bond purchasers (government lenders) may be either commercial banks or the private sector (investors and funds).

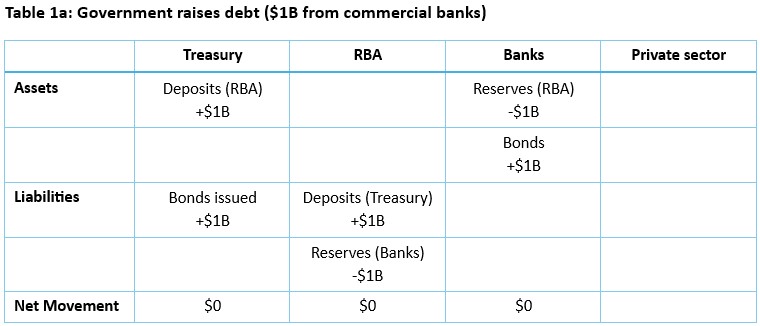

When banks buy Treasury bonds, they pay using their reserve balances held at the RBA. Base money falls. See Table 1a, for balance sheet movements between the involved entities.

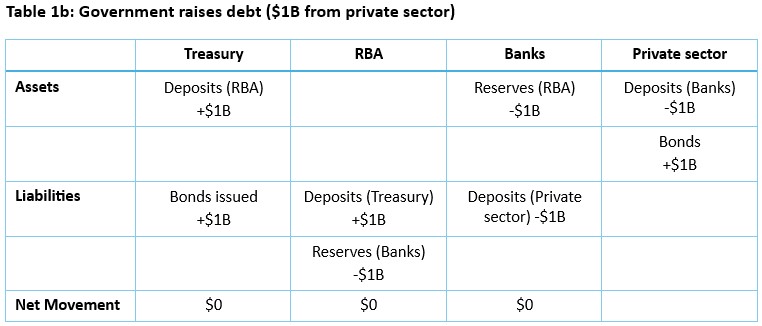

The private sector acquires bonds by exchanging bank deposits. Broad money falls. Matching bank deposit liabilities also fall, with a corresponding fall in reserves as they transfer funds on the private sector’s behalf. Bank balance sheets contract, and base money falls. See Table 1b.

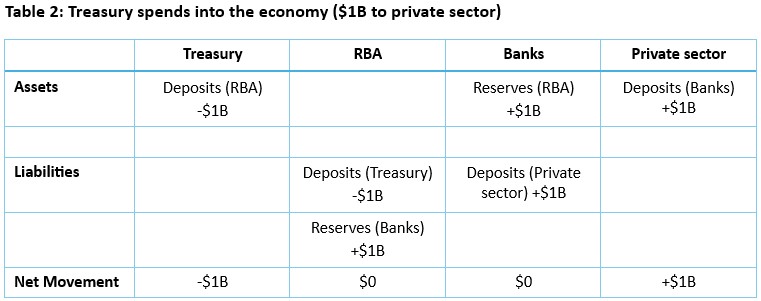

When government spending follows, Treasury deposits at the RBA fall, and bank reserves increase by a corresponding amount. Base money rises. The private sector is the recipient of the spending - bank deposits increase so broad money rises also. This can be inflationary if output can’t respond to increased demand. See Table 2.

How QE works

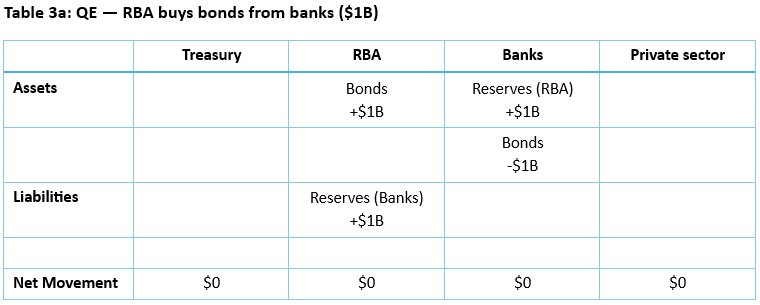

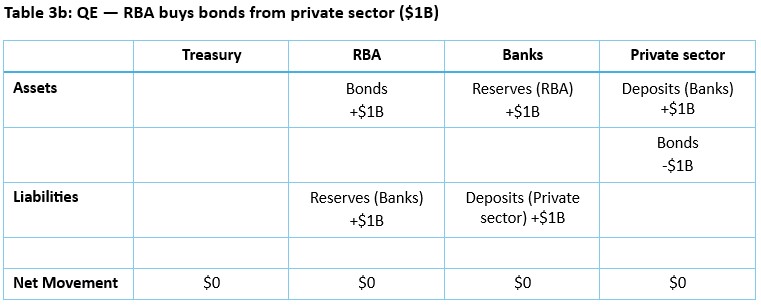

Turning to QE. The RBA buys government bonds from commercial banks or private sector investors. In both cases, it creates bank reserves to make the purchase - an RBA liability matching its newly acquired assets. If a bank is the seller, it swaps its bonds for the RBA created reserves. Base money rises, broad money is unchanged. If buying from the private sector, both bank reserves and private sector deposits increase, as the investor’s account is credited. The investor has swapped bonds for deposits. Both base money and broad money rises. See Tables 3a and 3b.

QE was employed aggressively by central banks during the pandemic, once conventional monetary policy hit its limits. With official cash rates already at or near zero, QE sought to lower borrowing costs further by reducing longer term interest rates and flattening the yield curve. Its design was to calm financial markets as governments imposed extraordinary economic restrictions.

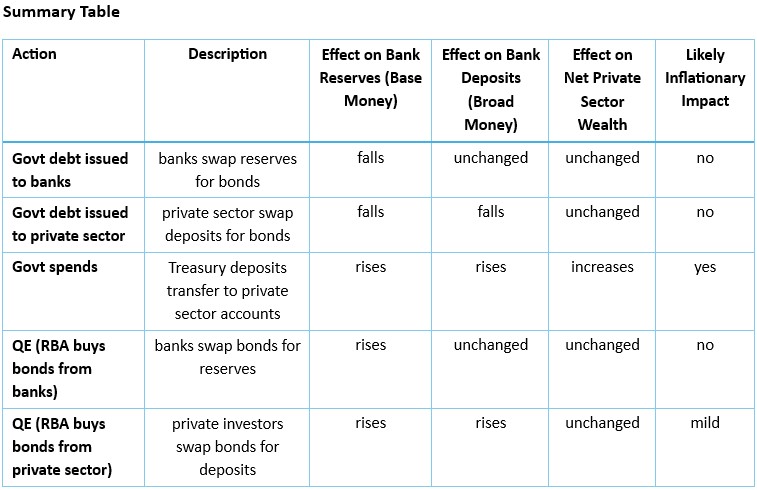

Key points with QE:

- QE creates new money in the form of bank reserves, but not spendable cash. It increases base money substantially, but any broad money increase will be limited to the extent that non-banks are bond sellers.

- The net financial wealth of the non-government sector is unchanged as bonds have been replaced by bank reserves and private sector deposits. Yes, liquidity has risen and can influence spending in the economy, but QE has been more a case of asset swapping than money creation.

- QE changes the composition, not the quantity of private sector wealth. Replacing longer term debt with short term bank reserves and deposits, it shortens the duration of holdings. In response, investors rebalance their portfolios, bidding up prices on the remaining pool of bonds and other long-term assets, driving down long-term yields.

- Even with an increase in broad money when the RBA buys bonds from private investors (super funds, insurers, individuals), it is likely they will seek to re-invest elsewhere rather than spend into the economy, such that the effect on demand would be minimal. And there is no change in broad money when banks sell their bonds.

- QE alone is rarely inflationary. It provides more liquid purchasing power, but minimal new purchasing power. By itself, it doesn’t directly create spending in the economy.

- QE sets the scene for fiscal expansion with added liquidity, but it is really deficit spending that lifts private sector wealth and drives demand.

What’s clear from this table is that only fiscal spending directly increases private sector wealth, while the other actions shuffle existing financial assets around. However, QE enhances liquidity, and if increased reserves encourages banks to lend more, and there is a private sector willing to borrow, then QE has laid the groundwork for broad money growth and for potential inflation.

(Note: bank reserves are not public money and can’t be lent out. When a bank lends money, it credits the borrower’s account with a deposit while simultaneously recording a matching asset and liability in its balance sheet. The deposit is new money.)

And while fiscal spending alone can be inflationary, it becomes even more potent when combined with QE, which adds liquidity to the equation. In an economy at near capacity, deficit spending provides the fuel for inflation, and QE the accelerant.

We saw this during Covid. The enormous injection of liquidity and fiscal stimulus set the scene for a potential inflationary surge. There was little concern at the time however, with inflation persistently low for years, and demand in the economy severely stilted by the pandemic. Then with the combination of ultra-low interest rates and bank reserves awash, asset prices soared and demand awakened from its slumber as economies opened back up. But in a world in the grip of severe supply constraints, an almighty surge in global inflation was triggered, and the rest is history.

It is also worth noting that when government spending coincides with a QE program, the combined outcome can effectively resemble ‘monetary financing’. That is, Treasury issues debt to fund its deficit, and when the central bank purchases equivalent debt, it can appear that the central bank has financed that spending.

Technically, this is not monetary financing, because the central bank trades in the secondary market rather than directly with Treasury. Yet there could be a perception of dependence when central bank independence is fundamental in advanced economies. It is generally understood however, that QE is temporary, with the expectation that QT will eventually unwind it. Along with any ‘appearance’ of monetised debt.

Quantitative tightening

Moving onto QT. Consider the passive form that the RBA is undertaking.

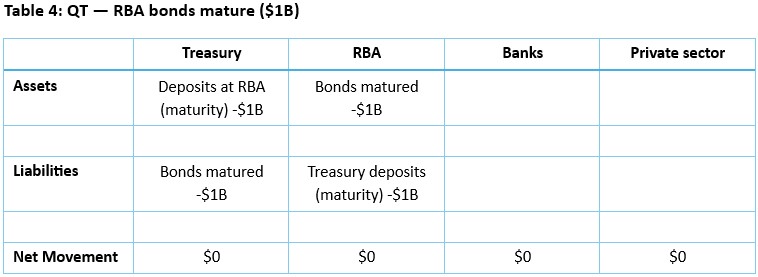

When government bonds held by the RBA mature, Treasury pays for the redemption from its deposit account at the RBA. The RBA’s assets and liabilities fall and its balance sheet contracts. Treasury then issues new debt to replace its deposits. Banks or investors buy the new bonds and the reversal of QE is complete. See Table 4.

Therefore in theory, QT is the mirror of QE. The former returns bonds to the private sector extinguishing bank reserves and base money, while the latter removes bonds from the market, creating reserves. Both actions change the composition of private sector assets, but not the aggregate. In practice though, they are not an exact mirror. Because economic context can dictate the scale and timing of execution of each. For example, a country running a large fiscal deficit will add reserves and liquidity to the system through its spending. And if the goal is to run down liquidity, a more aggressive QT policy may be required.

Implementing QT and cutting interest rates simultaneously can pull in opposite directions. This is because lowering interest rates, cuts the price of money, stimulates lending and demand, easing financial conditions. While QT sees the RBA balance sheet contract, drains bank reserves, tightens liquidity, and hardens financial conditions. The former is expansionary, the latter contractionary.

However, it is possible for the two programs to coexist. A large central bank balance sheet is abnormal, and while perhaps acceptable in an emergency period like the pandemic, it is less so in normal times. QT helps restore a more typical balance sheet and affects long-term interest rates, helping preserve a more typical yield curve as short-term rates decline.

Bank reserves that remain excessively high with interest rates falling, can create credit conditions that are too loose which can distort asset prices. QT can rein this in. Employing QT even while cutting rates, signals the responsible normalising of policy.

And we have seen post-pandemic, an expanded balance sheet that has exposed the RBA to accounting losses due to a mismatch between the long-term bonds that it holds, and the short-term liabilities it has issued. Passive QT would allow the RBA to run-off its bond holdings at face value such that no capital loss is realised. Whereas active QT would crystallise any capital losses.

The challenge is to get the balance right. If QT is too aggressive, it can undo the effects of easing monetary policy. If gradual with a framing of normalisation as opposed to tightening, it can complement a rate-cutting cycle. The RBA approach.

Interestingly, central banks around the world are taking different approaches to QT, depending on the state of their economies. The Federal Reserve in the US is reinvesting some of the maturity proceeds, slowing down QT and the shrinking of its balance sheet. Meanwhile, the Bank of England is speeding up the process by selling some of its holdings before maturity.

Even though QE had existed in some form before, the sheer magnitude and speed with which it was employed by central banks during the pandemic was unprecedented. Now that the dust has settled, the painstaking task of exiting those extraordinary settings is proving to be a delicate balancing act. And it remains to be seen what lessons policymakers have learned in the wake of central bank accounting stresses, and what path will be taken when the next crisis arrives.

Balance sheet movements

Note: overlaying Table 4 with Table 1a or 1b, yields the reverse of Table 3a or 3b (i.e: QE reversed).

Tony Dillon is a freelance writer and former actuary. This article is general information and does not consider the circumstances of any investor.