In our previous GQG Research, Dotcom on Steroids, we explored the striking parallels between the current AI landscape and the euphoric rise—and subsequent fall—of the late 1990s technology, media, and telecommunications bubble. In this follow-up piece, we delve into OpenAI, and take a hard look at the numbers, narratives, and risks separating the technological marvel from the economic reality.

Scaling the heights, ignoring the cracks

On the surface, OpenAI may sound like a Mag 7 company in its early days—unprofitable, burning through cash, and a magnet to investors who think they have found the next pot of gold. Peel one layer or dare to bring out your calculator for a closer look, and OpenAI goes from being the world’s “most valuable start-up” to what we believe is one of the most overvalued and overhyped companies in history.

In our view, the company’s financials are broken and unrealistic even if you lower the standards and look at them through the lens of a start-up with potentially revolutionary technology. OpenAI is more capital intensive than any other start-up we have seen, lacking the stickiness, the moat, and the network effect that have paved the way for other tech success stories. In addition, the disconnect between OpenAI’s revenue and valuation is alarming by any historical standard. As a comparison, consider Amazon or Google in their earlier days: when these companies had a $500 billion valuation, their revenues were roughly 10x and 4x as large, respectively, in comparison to OpenAI’s current run-rate revenue of ~$20 billion.1

As a long-only large cap manager investing in listed equities on behalf of its clients, most of the time we have the luxury of ignoring the less transparent world of private companies and some of their egregious valuations. So why is that different today? We are facing a unique situation where most of the large public players in tech are intertwined in a web of circular financing where money and deals flow through OpenAI. These relationships have direct implications for not just the large tech companies in our investable universe, but also many other companies in the S&P 500 in our view.

OpenAI is also playing a key role in driving the “hopes and dreams” factor, which we believe is helping to fuel this AI bubble. They believe Large Language Models (LLMs) will continue seeing meaningful step-function improvements toward this goal of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), a notion a number of AI experts have started to pour cold water on.2,3 In short, we see OpenAI as a capital-intensive business model that offers a product that faces meaningful risks of becoming a commodity. Yet, it continues to magically prop up valuations of its “partners” after each deal announcement.

Explosive growth, unprecedented spending

To give credit where it is due, OpenAI has firmly established itself as a leading innovator with its LLMs. Its market leadership is evidenced by rapid user adoption of their ChatGPT product which has swelled to over 800M weekly active participants and many large enterprise customers, in addition to revenue of billions of dollars, in the span of a few years.4,5

However, success is rarely free.

This explosive growth has been financed by record-breaking capital infusions and expenditures to build the infrastructure to support it.6 This unprecedented level of spending is underwritten by market forecasts of what we view as extraordinary economic gains that may ultimately prove to be unsustainable. While these investments signal widespread enthusiasm, they obscure the structural challenges that threaten OpenAI’s path to durable profitability. Despite the hype, the translation of this breakthrough technology into a resilient business is far from certain.

We will delve into OpenAI’s dynamics from an economic and technology perspective to illustrate why we believe it fails the proverbial “smell test” given that most analysts seem to be ignoring the facts.

The myth of the metric

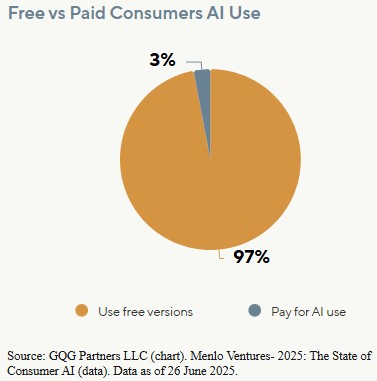

While impressive on the surface, high usage metrics (of which OpenAI has many to showcase) can often mask fundamental weaknesses in the quality of demand for a product and its ability to retain users. Specifically, a significant portion of OpenAI’s current user engagement is largely driven by free-tier users using it for non-productive reasons.7,8 This type of usage inflates activity metrics used for raising copious amounts of capital, but we believe it holds little signaling power for future revenue, making it a poor proxy for sustainable customer value. Not to mention that 90% of ChatGPT users are outside of the United States. Furthermore, we believe the translation of enterprise use into durable and sticky revenue is undermined by several key factors:

Persistent Reliability Gaps: LLMs continue to struggle with hallucinations.9 Their lack of consistency erodes trust and makes it difficult for the models to be embedded in mission-critical, multistep applications or operations that generate recurring, high-value revenue.

Fragile Adoption and Low Switching Costs: The current user base is heavily weighted toward free-tier participants who have no financial commitment to the platform.8 Even for paying enterprise customers, switching costs remain low for now. Currently, 28% of OpenAI’s API usage flows through low-code platforms like Zapier, Bubble, and Retool.5 These companies are model agnostic and can easily redirect workflows to better or more cost-effective models as they become available, including open-source models.

Questionable Performance Benchmarks: Extreme growth expectations are often justified by referencing the improving model performance on AI benchmarks.10 However, this too gives us pause. Some studies are beginning to show how these models have “gamed” benchmark results by “memorizing” the questions rather than understanding the subject.11 Beyond this technicality, the benchmarks create what we believe is a conceptual mismatch between what they measure and what enterprises value. They reward a model’s breadth of capability, making it an impressive generalist, yet corporations tend to be structured around the reliability of specialist employees performing a certain set of tasks with consistency.

The cheaper it gets, the more you pay

Even if user engagements were a perfect proxy for value, the basic economics of generative AI present a challenge. While the cost per token has plummeted due to hardware and software innovations, the cost per query has not seen the same dramatic decrease.12

With the mainstream adoption of reasoning models, the economics of LLM usage have shifted dramatically.13 Paying consumers are charged for each token the model takes as input and each token that the model outputs. It is important to note that users are charged more for tokens generated by the model than the tokens that are input. While the general cost per token has plummeted due to hardware enhancements, the number of tokens consumed per task has not.

An analysis by an AI gateway provider revealed an interesting trend: simple, single-turn queries, which constituted 80% of enterprise usage in early 2024, dropped to just 20% by year end. They were replaced by multi-step, complex workflows that drive up token consumption for each request, with most of them being the costlier output tokens.14

Will generative AI get sufficiently better from here?

It is not unusual for companies to invoke the promise of AGI when pressed on whether today’s use cases justify the massive amount of AI infrastructure investment companies are making. What should be unsettling is that the notion of near-term AGI is increasingly challenged by researchers and operators (including OpenAI founders themselves), with evidence of continued scaling and deployment realities pointing to a longer, harder road for advancement.2

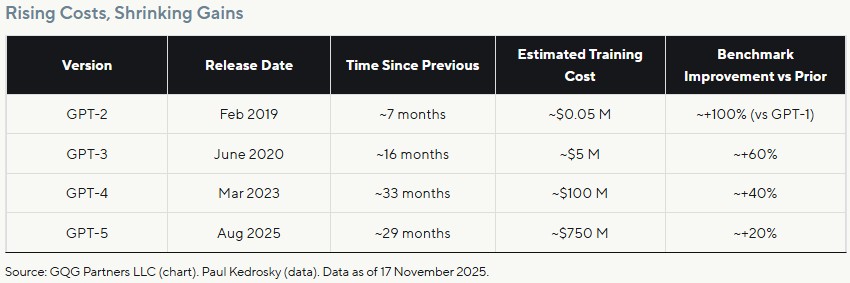

But let us lower the standards a bit and put AGI to the side—can AI, as we know it today, meaningfully improve? Was GPT-5 materially better than its predecessor, and was its rate of improvement comparable to the step up from GPT-3 to GPT-4? A cursory glance at release cadence, benchmark deltas, sharply rising compute, and power requirements suggests step-function gains are becoming rarer and more expensive—an uncomfortable backdrop for valuations and hype that implicitly assume (need?) continued leaps.

The uncomfortable truth is that this technology is running into hard constraints: the reservoir of high-quality human data is finite, returns to scale are slowing, and a recursive reliance on synthetic data risks degrading the signal. As a result, products like ChatGPT look a lot less like software with zero-marginal-cost scale and more like metered compute with rising variable inputs and operational choke points.

The illusion of scale

The unit economics of LLM providers do not seem to align with the high-margin, scalable models of successful Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) and marketplace companies. Unlike a SaaS model, the cost of adding a new LLM customer is not zero because the cost of compute for LLMs scales with the users, leading to an organic barrier to economies of scale that this business model can achieve. And unlike Uber, as an example, an LLM does not benefit from network effects in that the value of its service does not inherently improve as more users engage with it.

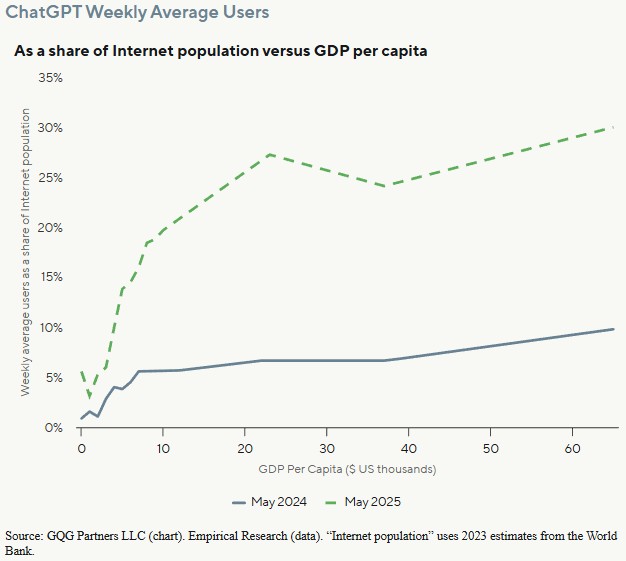

However, this flawed comparison appears to be driving a classic Venture Capital-subsidized “blitz-scaling” strategy that is now playing out globally. As shown in the graph, AI adoption has been unequal between geographies with varying GDP per capita. The lowest adoption rates can be seen in low GDP per capita countries, which tend to be more price sensitive, so providers seem to be using deeply subsidized pricing to capture users in these markets.

OpenAI, for instance, has introduced local plans in India, its biggest market after the US, at a fraction of the global price. Also in India, Perplexity, an AI-powered search engine, is bundling $20 per month subscriptions for free in mobile plans where telecom providers generate as little as $3 per month in revenue per user. It is difficult to rationalize how acquiring these highly price-sensitive users contributes to the future profitability that current valuations demand.

If growth within the consumer market relies on unsustainable subsidies, the hope for profitability must lie with enterprise adoption. This has been a comparatively bright spot, with enterprise spending on foundation models more than doubling in the first half of 2025. However, we believe this optimism is tempered by significant headwinds.

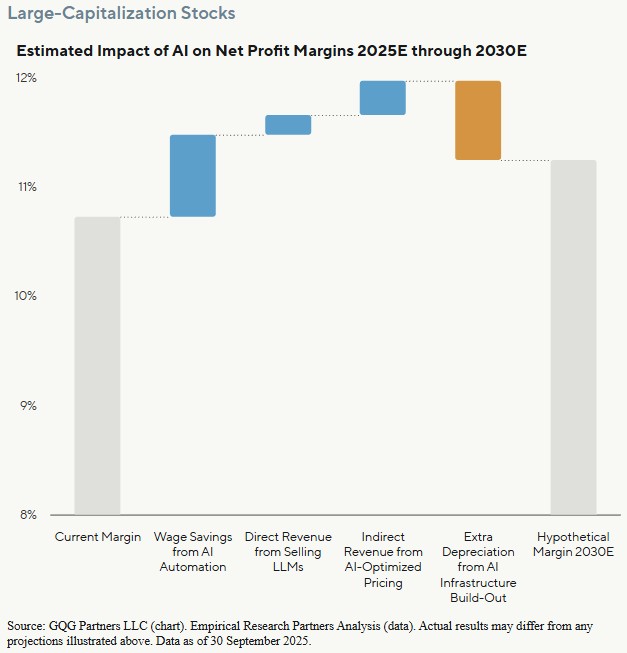

A few recent studies found that either companies remain in a perennial pilot phase for AI projects, or that most pilot programs for incorporating AI end up failing.15,16 Furthermore, even successful adoption may yield only marginal gains. A recent study estimated AI’s net impact on enterprise profit margins by 2030 at a mere 50-70 basis points.17 While not immaterial, this margin uplift is expected to come primarily from job automation (which we think is becoming an increasingly questionable assumption18) and offset by the significant depreciation expenses of the required AI infrastructure (which is a known and unavoidable cost).

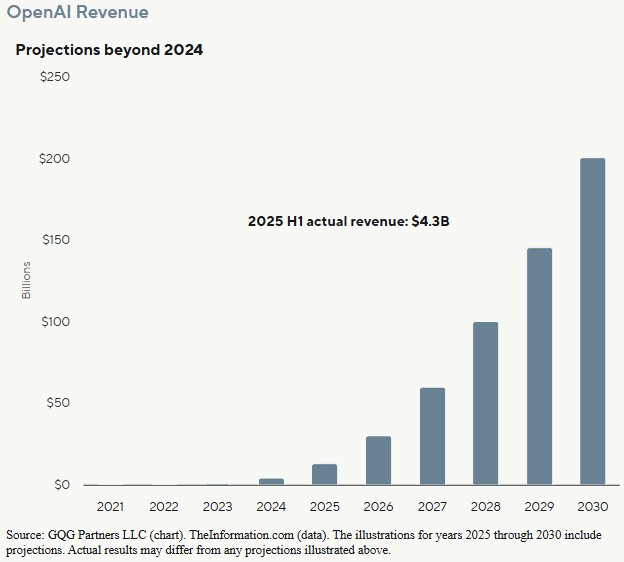

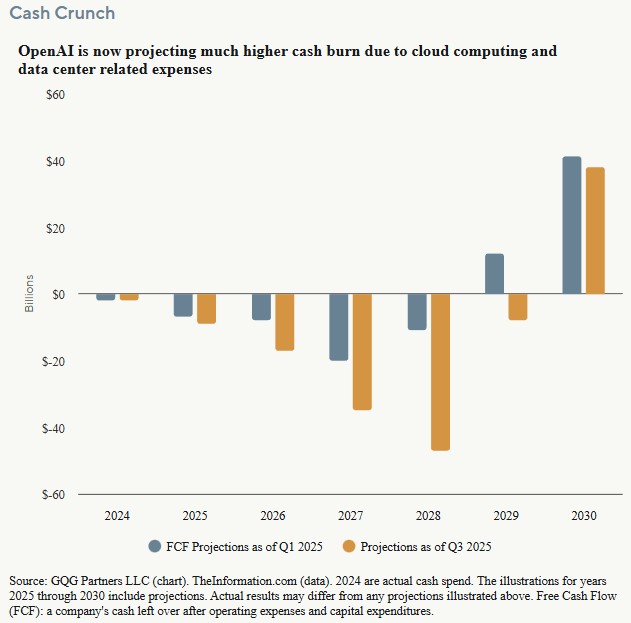

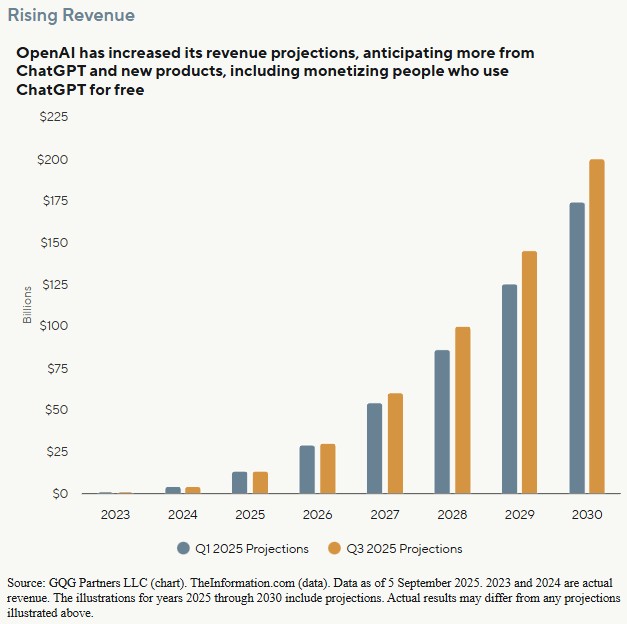

The hard financials make this picture even bleaker. In the first half of 2025, OpenAI generated $4.3 billion in revenue while posting a net loss of $13.5 billion and burning through $2.5 billion in cash. Despite this staggering burn rate, the company projects it will be profitable by 2030, with revenues soaring to $200 billion and gross margins over 60%.19 This type of long-range, hockey-stick forecast for a business with such a murky path to profitability is eerily reminiscent of the dotcom era, where many companies extrapolated short-term hype into extreme future earnings that never materialized.20

For context, a $200 billion revenue target would exceed the 2024 sales of Nvidia, a company that operates as a near-monopoly with immense barriers to entry and is years ahead of its closest competitors, something we believe OpenAI can hardly claim considering how easily interchangeable frontier language models are.21 To suggest that OpenAI—a company burning through cash by the billions amid fierce competition with seemingly no durable moat—will achieve a similar financial profile in just a few years seems less like a forecast and more like a work of speculative fiction in our view.

We believe there is another underappreciated risk: the intense competition for talent among the AI labs. OpenAI is on track to spend close to $6 billion on stock-based compensation in 2025 alone.22 Since these are all based on the company’s ~$500 billion valuation, even a modest slowdown could heighten the challenge of retaining key employees. However, despite the possible headwinds, OpenAI continues to raise its revenue expectations.

This all leads back to one unavoidable consequence: the math seemingly does not work, and the capital-intensive nature of the business creates relentless liquidity pressure. Despite record-breaking revenue, OpenAI has raised over $40 billion this year, up from $6.6 billion in 2024, all in addition to revolving credit lines and infrastructure partnerships. To keep up their growth, arguably by subsidizing the cost of compute for users and maintaining their high-in-demand workforce, we think they will need to keep raising money at record-breaking rates.

Using a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation, taking the 136 million US private workforce at the going subscription rate of $20 per user per month yields less than $3 billion in revenues—and of course that is before discounts, usage caps, or reseller splits. To put this into perspective, Google raised just $26 million (~$60 million in today’s terms) before becoming profitable, while Meta raised about $480 million (~$800 million today).23,24 By comparison, OpenAI is projected to burn through a staggering $115 billion before it even hopes to reach free cash flow profitability in 2030.25 The scale of this capital consumption is without precedent.

Immortal tech, mortal company

LLMs are not a bad asset, but the price being paid for a business with such immense capital costs, no obviously durable moat, and questionable unit economics may prove to be fatal. We believe the story to watch is not whether the technology is immortal (it most likely is), but whether the companies building it are.

This article is an abridged extract of GQG Partners’ recent long-form article “Dotcom on Steroids Part II”. You can read the full article here.

End notes

1Capoot, Ashley. “Sam Altman says OpenAI will top $20 billion in annualized revenue this year, hundreds of billions by 2030”. CNBC. 6 November 2025.

2Roytburg, Eva. “Did an OpenAI cofounder just pop the AI bubble? ‘The models are not there’”. Fortune. 21 October 2025.

3Patel, Dwarkesh. “Richard Sutton – Father of RL thinks LLMs are a dead end”. Dwarkesh Podcast. 26 September 2025.

4Bellan, Rebecca. “Sam Altman says ChatGPT has hit 800M weekly active users”. TechCrunch. 6 October 2025.

5Elad, Barry. “OpenAI Statistics 2025: Adoption, Integration & Innovation”. SQ Magazine. 7 October 2025.

6Tap Twice Digital Team. “8 OpenAI Statistics (2025): Revenue, Valuation, Profit, Funding”. Tap Twice Digital. 18 May 2025.

7“OpenAI’s Shocking Revelation: 70 % of ChatGPT Use Isn’t for Work”. Open Tools.ai. 22 September 2025.

8Carolan, Shawn, et al. “2025: The state of Consumer AI”. Menlo Ventures. 26 June 2025

9Dilmegani, Cem and Daldal, Aleyna. “AI Hallucination: Comparison of the Popular LLMs”. AIMultiple. 20 October 2025.

10“AI Benchmarking”. epoch.ai.

11“The Sequence Opinion #485: What’s Wrong With AI Benchmarks”. TheSequence. 6 February 2025

12Spark, Zoe. “The LLM Cost Paradox: How ‘Cheaper’ AI Models Are breaking Budgets”. IKANGAI. 21 August 2025.

13 IBM.com. “What is a reasoning model?”. Reasoning models are a new type of LLMs designed to solve complex problems by performing structured, multi-step thinking before providing an answer. They typically use more tokens while processing their answers.

14Sambharia, Siddharth. “LLMs in Prod 2025: Insights from 2 Trillion+ Tokens”. Portkey. 21 January 2025.

15Singla, Alex, et al. “The state of AI in 2025: Agents, innovation, and transformation”. QuantumBlack AI by McKinsey. 5 November 2025.

16Nanda, Mit, et al. “The GenAI Divide. The State of AI in Business in 2025”. mlq.ai. July 2025.

17Empirical Research Partners. “AI and Margins: A New, New Economy?”. September 2025.

18Kinder, Molly, et al. “New data show no AI jobs apocalypse—for now”. Brookings. 1 October 2025.

19Muppidi, Sri. OpenAI Forecasts Revenue Topping $125 Billion in 2029 as Agents, New Products Gain”. The Information. 23 April 2025.

20Smriti. “Pets.com failure: Learn from one of the biggest innovation failures”. InspireIP. 4 October 2023.

21King, Ian. “Why Is Nvidia the King of AI Chips, and Can It Last?” Bloomberg. 5 November 2025.

22Palazzolo, Stephanie, et al. “OpenAI’s First Half Results: $4.3 Billion in Sales, $2.5 Billion Cash Burn”. The Information. 20 September 2025.

23“How Much Did Google Raise? Funding & Key Investors”. Clay. 9 May 2025.

24“How Much Did Meta Raise? Funding & Key Investors”. Clay. 24 March 2025.

25“OpenAI expects business to burn $115 billion through 2029, The Information reports”. CNBC. 6 September 2025.

Definitions

AI benchmarks: standardized tests that evaluate and compare the performance of artificial intelligence systems, using a specific dataset or set of prompts and a scoring method to measure performance on a particular task.

Capital-intensive: a business or industry requires a large investment in physical assets like machinery, equipment, and buildings to produce goods or services.

GDP per capita: a country’s gross domestic product (GDP) divided by its population.

Hallucinations: When a large language model perceives patterns or objects that are nonexistent, creating nonsensical or inaccurate outputs.

Cost of inference: the total expense of using a trained AI model to generate an output, including resources like computing power, energy, storage, and network usage.

Closed Source vs Open Source: Open-weight models provide access to the model’s parameters (weights), allowing for customization, while closed-weight models are proprietary and accessible only via an API. Key differences include customization and control, security and privacy, and innovation and flexibility. Open-weight models offer greater flexibility and security for sensitive data, while closed-weight models provide convenience and potentially higher initial performance through a managed API.

This article contains general information only, does not contain any personal advice and does not consider any prospective investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. Before making any investment decision, you should seek expert, professional advice.