Howard Marks is a billionaire debt investor and he’s the first to admit that he isn’t active in stock markets and is far from a tech wizard. However, he is a long-time observer of investor psychology and has successfully called out both the tech bubble in the 1990s and the subprime bubble which preceded the GFC.

Understanding bubbles

In his latest investor memo, Marks goes into detail about what bubbles are, how they develop, the impact they have, and whether today’s AI boom can be characterised as a bubble.

He says all bubbles follow similar patterns. A new and seemingly revolution development happens and it captures people’s imaginations. Early investors enjoy phenomenal gains. Others on the sidelines get jealous of these gains and eventually pile in. They do this regardless of the prices on offer or the risks attached. Eventually, it goes pear-shaped and most investors who got in late wear considerable and often irreparable losses.

If the damage is so bad, why then do bubbles recur? Marks says investor memories are short, and “prudence and natural risk aversion are no match for the dream of getting rich on the back of a revolutionary technology that “everyone knows” will change the world.”

Marks suggests that bubbles typically form around new financial developments – think of the South Sea company of the 1700s or subprime mortgages in 2005-2006 – or technological progress – like rail in the 1900s, and optical fibre/the internet in the 1990s.

The “newness” of a financial development or technology plays a part. A new thing can’t be guided by history and the future for the new thing can appear limitless. That’s when bubbles can form and market prices can become detached from underlying values.

Marks takes aim at those technology enthusiasts who believe that bubbles are positive as they lead to money pouring into an area, jump-starting investment, and laying the groundwork for future prosperity. He says bubbles based on both financial developments and technology can lose a lot of money along the way:

““Mean-reversion bubbles” – in which markets soar on the basis of some new financial miracle and then collapse – destroy wealth. On the other hand, “inflection bubbles” based on revolutionary developments accelerate technological progress and create the foundation for a more prosperous future, and they destroy wealth. The key is to not be one of the investors whose wealth is destroyed in the process of bringing on progress.”

What about the current AI boom?

Marks thinks there’s little doubt that AI has the potential to be one of the biggest technological developments of all time, reshaping economies and people’s lives.

And he notes that the US economy has become more reliant on AI investment, and the US stock market has leaned heavily on the performance of AI stocks:

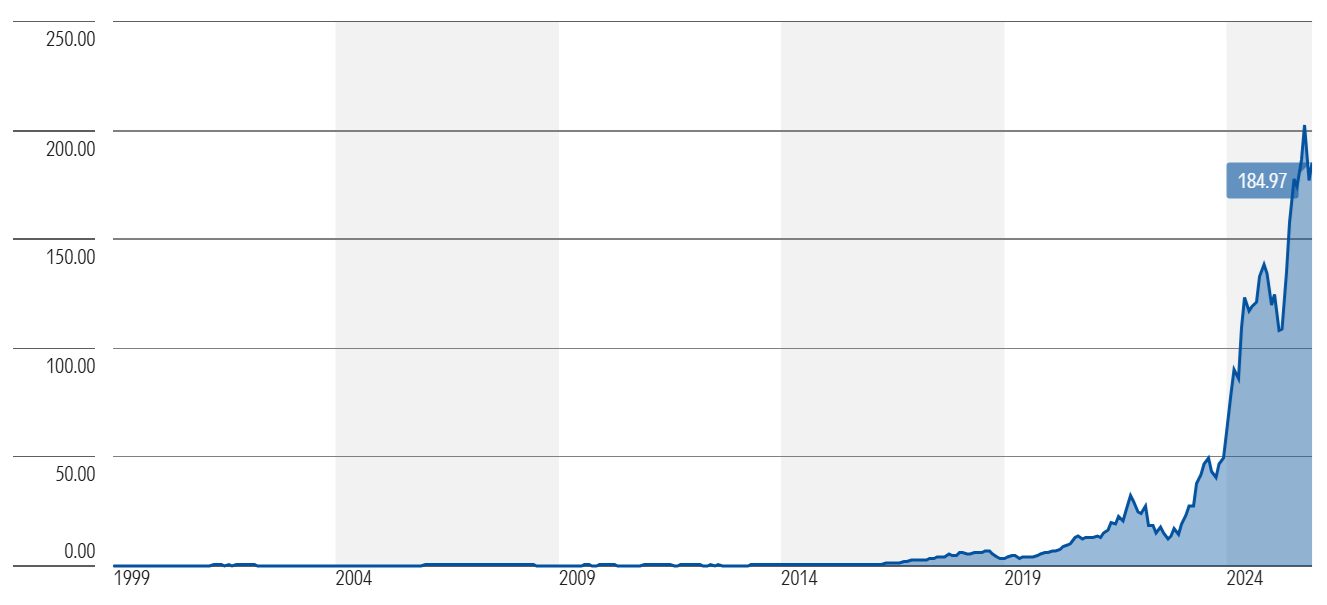

“AI-related stocks have shown astronomical performance, led by Nvidia, the leading developer of computer chips for AI. From its formation in 1993 and its initial public offering in 1999, when its estimated market value was $626 million, Nvidia briefly became the world’s first company worth $5 trillion. That’s appreciation of around 8,000x, or roughly 40% a year for 26+ years. No wonder imaginations have been fired.”

Nvidia’s share price

Source: Morningstar

Despite the market enthusiasm, Marks says there’s still a lot of uncertainty about how the AI boom will play out. Some of the questions he has include:

1. Who will be the winners, and what will they be worth?

Marks suggests that there are strong AI leaders right now, though technology is notoriously disruptive, and no one knows whether today’s leaders will prevail or whether they’ll give way to upstarts.

2. What’s a share in an upstart worth?

Extraordinary money is being thrown at AI startups and Marks questions what the returns on these investments will be. He cites the case of a firm called Etch, formed by college dropouts, which raised US$120 million to build a new AI chip to take on Nvidia.

3. Will AI produce profits and for whom?

Will AI be a monopoly or duopoly, or will there be hundreds of different players? What impact will AI have on the companies that use it? Will it enable businesses to cut costs and increase margins, or will those improved margins result in price wars which will eventually shrink margins?

4. Should we worry about so-called “circular deals”?

Most of you will be familiar with the recent deals between large AI firms, and the circular nature of these announcements. Marks queries whether these transactions will achieve legitimate goals, or whether they’re just a way to bump up short-term profits.

5. What will be the useful life of AI assets?

The lifespan of AI chips is a big topic in the tech world, and no one has an answer about where it will end up.

6. Is exuberance leading to speculative behaviour?

Mark cites the “extreme example” of AI startup, Thinking Labs, which raised money at a US$10 billion valuation two months ago, and is now in early talks to raise more money at a valuation of US$50 billion.

7. What’s the end state?

Even AI builders don’t know what type of general intelligence will be created or what kind of returns they’ll make.

8. Is the increasing use of debt a concern?

There’s been much talk of AI companies taking on significant debt to fund their investments. Mark says the use of debt is neither good nor bad, but how it’s applied that counts.

On AI and debt, he quotes Oaktree colleague, Bob O’Leary:

“Most technological advances develop into winner-takes-all or winner-takes-most competitions. The “right” way to play this dynamic is through equity, not debt. Assuming you can diversify your equity exposures so as to include the eventual winner, the massive gain from the winner will more than compensate for the capital impairment on the losers. That’s the venture capitalist’s time-honored formula for success.

The precise opposite is true of a diversified pool of debt exposures. You’ll only make your coupon on the winner, and that will be grossly insufficient to compensate for the impairments you’ll experience on the debt of the losers.

Of course, if you can’t identify the pool of companies from which the winner will emerge, the difference between debt and equity is irrelevant – you’re a zero either way. I mention this because that’s precisely what happened in search and social media: early leaders (Lycos in search and MySpace in social media) lost out spectacularly to companies that emerged later (Google in search and Facebook in social media).” [the bold text is from Marks’ memo]

So, from all this, what are Marks’ conclusions?

He sees no shortage of exuberance from investors chasing AI riches:

“There can be no doubt that today’s behavior is “speculative,” defined as based on speculation regarding the future. There’s also no doubt that no one knows what the future holds, but investors are betting huge sums on that future.”

However, Marks partially hedges his bets on whether AI is definitely a bubble. While there is exuberance, whether it’s irrational will only be known years from now, he says.

As to how investors should position their portfolios, Marks believes going all-in on AI risks possible financial ruin, while staying completely out risks missing out on one of history’s greatest technological leaps. He advises a moderate position in AI, applied selectively, as the best approach.

AI is coming for your job

Marks’ starkest warning comes with AI’s potential impact on jobs. He finds the outlook for employment “terrifying” because AI “may not be a tool for mankind, but rather something of a replacement.”

He uses examples of how AI has largely replaced ‘coders’ – computer programmers who write code – and digital advertisers with so-called ad matching (showing people ads tailored to the preferences displayed by their prior surfing).

Marks says more jobs will inevitably go, including drivers due to self-driving vehicles, entry-level workers, junior lawyers given AI can spit out legal precedents in seconds, radiologists as AI can read and interpret MRIs, and investments analysts given AI can do spreadsheets, business competitor analysis and much else:

“I find it hard to imagine a world in which AI works shoulder-to-shoulder with all the people who are employed today. How can employment not decline?” [bold text is Marks’]

If jobs are lost from AI, Marks can imagine governments stepping in with things such as ‘universal basic income’. But then the question will be where over-indebted developed market governments will get the money to fund such a scheme.

Marks doesn’t want to be a Debbie Downer on the topic, so he ends up on a more optimistic note. That is, with millions of Baby Boomers retiring over the next decade, perhaps AI can make up for this shortfall in jobs, and the larger economic impact may be more positive than feared.

Let’s hope so.

James Gruber is Editor at Firstlinks.