“You never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them.” Atticus Finch, To Kill a Mockingbird.

Fixed income securities – or bonds – have the most predictable returns of any asset class, yet they are often maligned and misunderstood by market commentators who want to call them risky.

Rather than launching into a conceptual response to these scurrilous accusations, this article takes a leaf from Atticus Finch’s book. It walks in the shoes of an actual fixed income security, one whose days on earth are just about over, but which has led a long and fulfilling life. It looks back on this bond since 2002, reflects on the fluctuations in its price and reviews how it performed for investors who owned it. Hopefully readers will feel that they then know the asset class much better.

The security in question is the Commonwealth Government Bond that will mature on 15 April 2015 at the ripe old age of 13 years.

Issued in May 2002, it promised to make two interest payments every year until April 2015, when it will return its face value to its owners. Its annual coupon rate was 6.25%, so the payments would be 3.125% of face value each in April and October. The rate of 6.25% was in line with market yields at the time, so investors who bought into the issue outlaid $100 for $100 face value (it was priced at par) and sat back to enjoy the steady income over the next 13 years.

The first year

The bond’s price didn’t stay at par for long. A fixed income security with over a decade until maturity is a frisky sort of animal and moves quickly if you prod it. Nowhere near as jumpy as shares, but still twitchy.

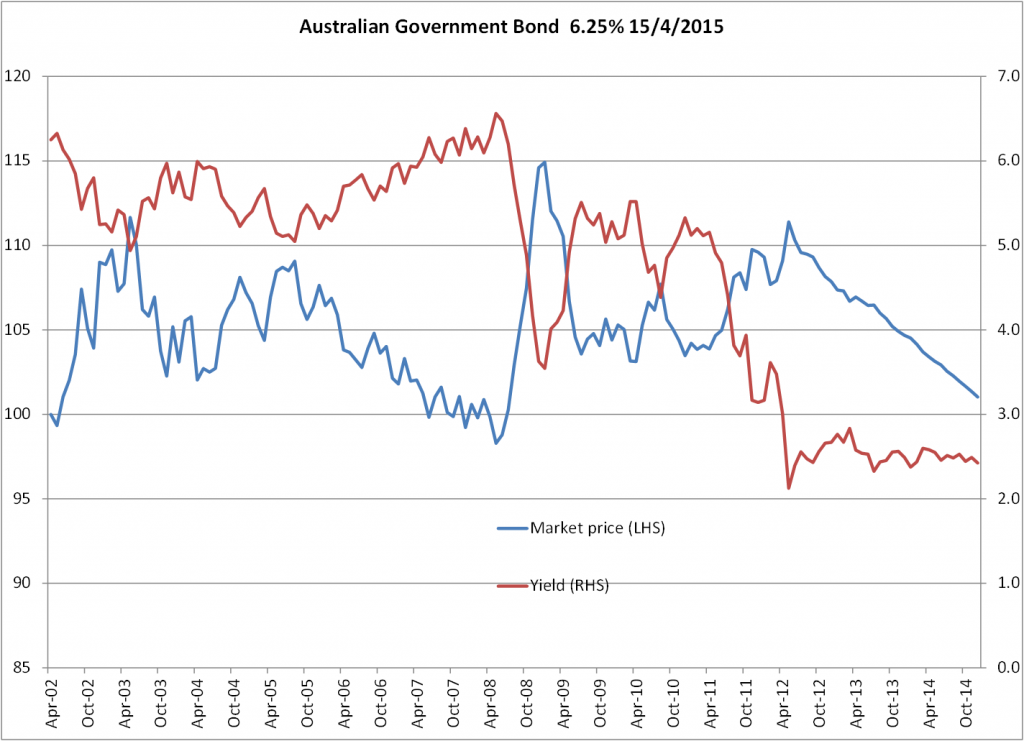

As it happened, over the remainder of 2002 bond yields fell, so our April 2015 security sharply appreciated in value. By its first anniversary in May 2003, it was priced to yield just under 5%, with a market value of nearly $111.90 (see Term deposit investors did not understand the risk for a refresher on the link between bond prices and market yields). Two interest payments had been made, totalling 6.25% of the initial outlay, which when added to the mark-to-market gain of 12% made for quite a handsome return of 18% over 12 months.

Some investors bailed out at that point, locking in their gain. Those who bought the bond from them would now expect to earn 5% per annum over the next 12 years, with the 6.25% coupon payments being offset by the amortisation of the bond from $111.90 to $100 over that period.

That first year pretty much set the trading range for the first half of our bond’s life. In yield terms, the market traded the April 2015 bond between 5 and 6% for several years.

Towards middle age

As the years went by, our bond became less frisky. To use the jargon of fixed income, it had a shorter duration. The next time the yield on the April 2015 bond got down to 5% was August 2005, when it had just less than ten years until maturity. Its price this time rose only to $109.

It’s as if during its life a bond looks more longingly at its destiny – par value at maturity – and starts to resist the pressure on its price that is exerted by fluctuations in market yields.

By the later months of 2007 and into 2008, investors wanted higher yields to compensate for higher inflation. The April 2015 was traded in the market at a yield above its coupon rate and its price fell below par. Around its sixth birthday in May 2008 the yield peaked at 6.5%, meaning that it hit the low price point in its life. The market at that time valued it at $98.30.

Popularity explodes

Things changed quickly in the second half of 2008. As the global financial crisis unfolded the demand for government bonds exploded. Our April 2015, along with his longer term cousins, had never been more popular. As the world financial system risked collapse, and the global economy faced deflation risk, the yields investors were willing to accept from bonds plummeted.

During October 2008, we were once again back at 5%. This time, as our bond was older and thus getting shorter in duration, its price reached only $106.

However, it didn’t stop there. As support for financial corporation debt fell in the opinion polls to all-time lows, the ‘yes’ vote for government bonds kept climbing. The April 2015 yield fell further - to 4.5%, then to 4.0% and eventually to a new low of just 3.5% by January 2009. Even though our bond now had only six years and a bit to maturity, it still had enough vigour to respond to this fall in yields with a price appreciation to $115. Heady days!

Popularity fades

However, after a while the smart money decided to move back into risk assets. Shares or corporate bonds – anything but government bonds yielding less than 4%. Just as quickly as our bond’s popularity had risen, it dropped. By the middle of 2009 it was again yielding above 5% and its price had fallen below $105. It would trade there for a couple more years, until the financial crisis mark II arrived.

Popularity returns

Our bond carried a AAA rating throughout its life which became highly valued by global investors from late 2011 when sovereign wealth funds and central banks were attracted like moths to a flame to the Australian government bond market.

Most of this demand was for securities longer than the April 2015, but our bond was carried in their slipstream back to lower yields. They reached 3.5% again around September 2011, though its vigour was beginning to fade and our bond could only rally to a price of about $109 this time. It managed to appreciate a bit further over the next few months, hitting $111 for its tenth birthday in May 2012. But it took an incredibly low yield of 2.1% to get it there.

Amortising to maturity

Since then, our bond has been enjoying a relatively lazy life. Its yield has traded around 2.5% for most of this time and its price action has been dominated by a steady trend towards par, where it will be valued when it retires in a couple of months. Its owners for these past three years have been receiving $3.125 each half year in coupon payments per $100 face value, but for that to yield them 2.5% pa there has also been a gradual decline in capital value of just under $2 each half year.

The following chart shows the price and yield history of the April 2015 bond in full.

A life well-lived

What have we learned from walking in the shoes of the April 2015 government bond?

First, that the life of a bond can sometimes be a wild ride. Its price fluctuated, sometimes rapidly, reflecting changes in market yields. Therefore its short term return also fluctuated. Rarely, if ever, was the annual return equal to the original yield of 6.25%.

Second, every time the yield got back to 6.25% it was valued at par, but as it happens this bond spent most of its life trading at a yield below that level and thus at a price above par.

Third, the fluctuations became smaller as maturity approached and the inexorable pull of par value became stronger. A yield that early in its life resulted in the price being well away from par produced smaller and smaller premia over time.

Fourth, the bond never missed a beat in paying the regular interest promised when it was first issued. Over the whole of its life, the April 2015 bond delivered. And from any point in its life, its new owners continued to receive the promised coupons plus a predictable rate of capital price amortisation. They could, therefore, easily predict the long term return they would make on their investment.

As its name implied, it provided its owners a regular fixed income. It’s been a bond’s life well-lived.

Warren Bird is Executive Director of Uniting Financial Services, a division of the Uniting Church (NSW & ACT). He has 30 years experience in fixed income investing, including 16 years as Head of Fixed Interest at Colonial First State. He also serves as an Independent Member of the GESB Investment Committee. This article is general education and does not consider any investor's personal circumstances.