For many, the Australian dream of home ownership has been drifting out of reach, with ownership rates trending down at least since the 1990s. Why does price growth remain so high? This is one of Australia’s most pressing public policy questions.

Most economists – including this one – agree that Australia should have more housing supply, which would ease prices and rents. Local governments decide zoning but do not factor in the broader economic benefits of supply growth. This is a strong justification for the Federal Government’s National Housing Accord, which incentivises state governments to work with local governments to lift supply. There are also costly and arguably ineffective bottlenecks in construction regulation.

Policy that addresses these issues is clearly beneficial. But the presence of supply constraints does not necessarily imply that they are the sole – or perhaps even the main – driver of Australia’s affordability issues. If other factors matter, then to be effective, housing reform may need to extend into other areas like tax settings and welfare-payment eligibility.

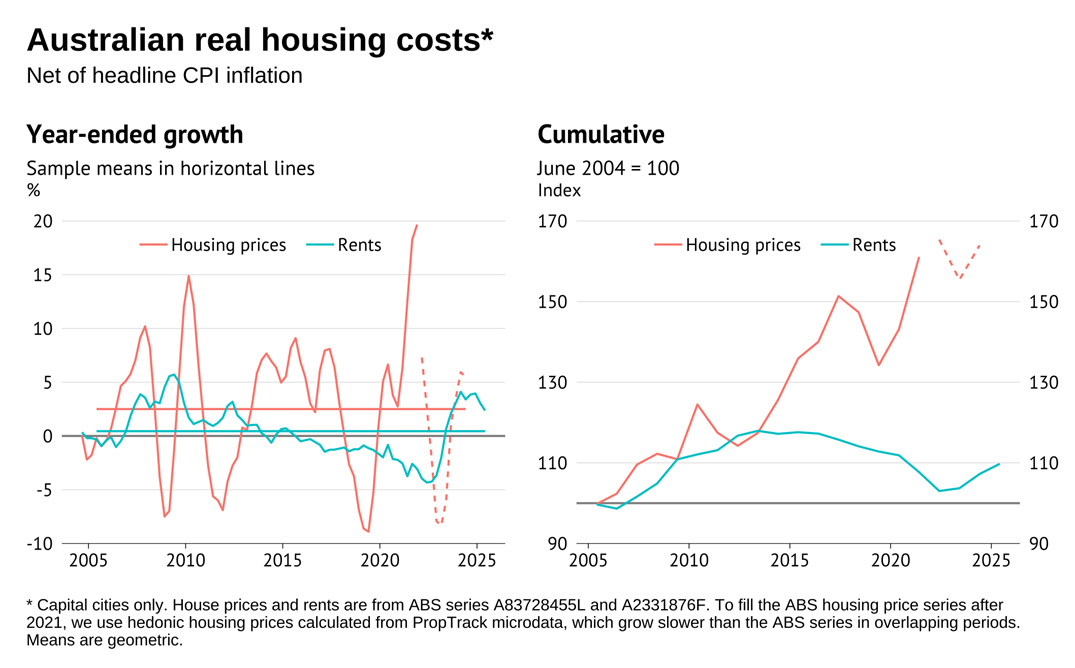

The aggregate trends in housing costs indeed suggest looking at other factors. Rapidly rising rents are a post-COVID phenomenon; over the longer term, worsening affordability is more a story of purchase prices. Relative to inflation, average rents across Australia’s capitals are now lower than in 2010. A sizeable difference between price and rent growth goes back to the 1980s.

Something is contributing to high price growth that appears to be having not much effect on rents. It is difficult to argue that rents are immune to supply shortages. Prior e61 work presents evidence that rents responded to shifts in supply-demand balances when COVID hit.

Some US research has modelled housing supply as affecting prices more than rents because supply shortages raise expectations of future rent growth. This boosts the expected profitability of buying, and therefore the price people are willing to pay. In Australia, price growth has remained strong despite slow rent growth. Here, this explanation would require that expectations about future rent growth remained high despite low growth eventuating.

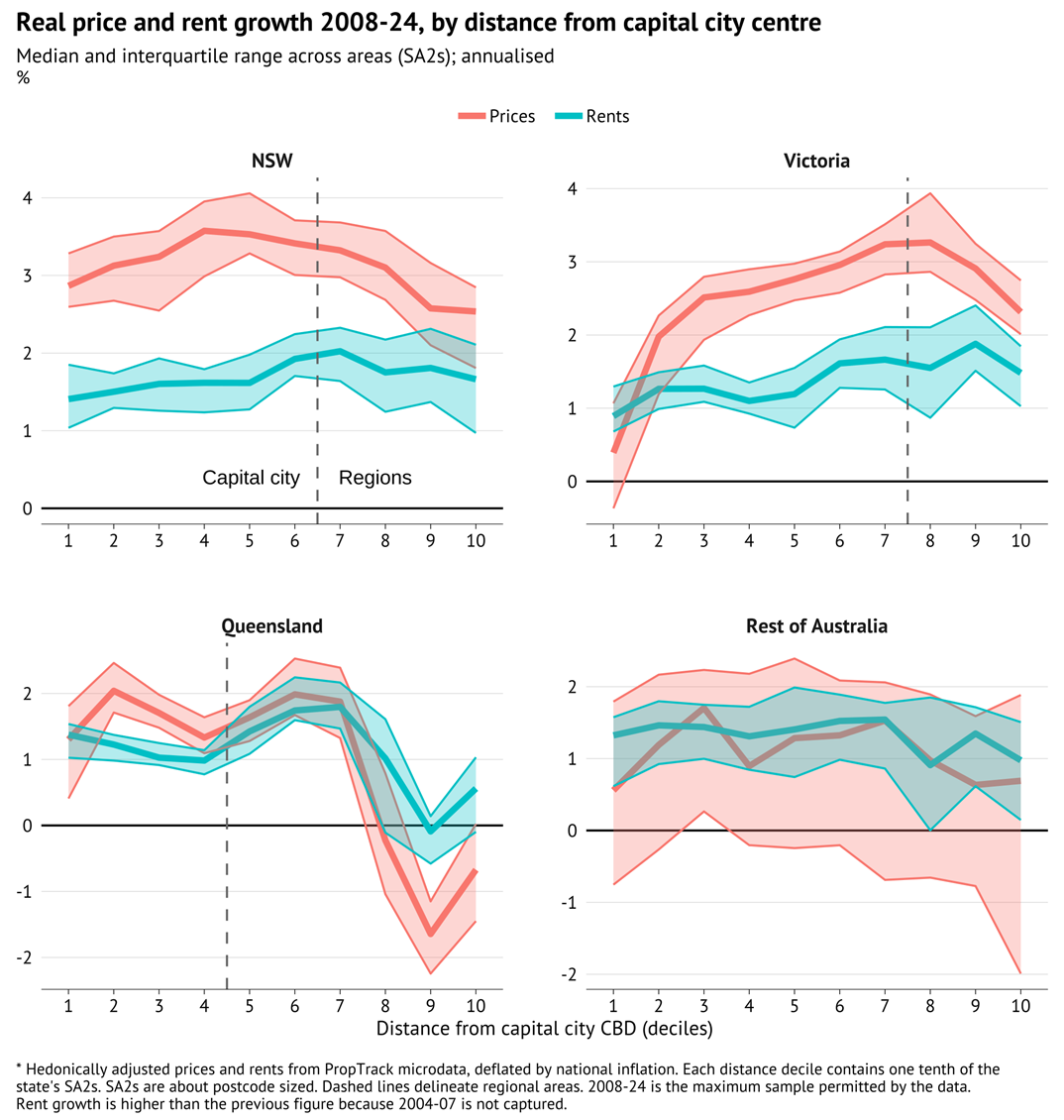

The growth difference between average prices and rents is not due to different locations of owner-occupied and rented housing. In fact, in Sydney – where housing supply is arguably most constrained – rent growth is furthest below price growth. In NSW and Victoria, rent growth has been a little higher outside the capitals than in them. At face value these patterns differ from the US, where rent growth has been faster in supply constrained areas.

These price and rent growth patterns can be reconciled by viewing housing as a financial asset, as per the workhorse user-cost model of housing prices. This seems appropriate because Australians do tend to see housing as a way of building wealth. Financial asset prices are driven by expected future returns: the more money someone expects to make from the purchase, the more they’re willing to pay. Access to credit can also play a role, if people are willing to pay more than they can afford, and their ability to pay changes. Recent Australian research concludes that past regulatory limits on mortgage lending lowered housing prices.

The user-cost model highlights that financial returns from housing primarily comprise capital gains from price growth, minus mortgage interest costs, plus rental income (which for owner occupiers is an avoided financial cost). If prices are rising much faster than rents, it suggests that expectations of capital gains are rising, or expectations of interest costs are falling, or ability to borrow and spend is expanding.

The reality is probably a combination of all three. On capital gains, US research models how shifting beliefs about future housing returns can have sizeable price effects. Regardless of how high prices get, there seems to be no shortage of advice to young people to get into the market to not get left behind. On interest costs, some Australian research has attributed rapid housing price growth to the long-term decline in interest rates. On credit, the ability of Australians to pay deposits – and to borrow the rest – has risen as household incomes have grown, and as past housing price growth has generated housing wealth that can be further borrowed against.

What’s the solution?

Tightening monetary policy to lower housing prices would most likely do more harm than good, by also depressing general economic activity. Alternatively, restrictions on borrowing would hit those without mortgages already locked in, and therefore unequally affect first home buyers, who the policy would be most aimed at helping. Current policy is intentionally doing the opposite – relaxing borrowing constraints for first home buyers.

Other ways of targeting expected future returns are worth consideration. Relative to other investments, Australia’s tax on housing is generous. Owner occupiers have a full capital gains tax exemption. Investors receive a 50 per cent discount on capital gains tax, which also applies to other investments like equities, but may have more effect in the housing market where leverage and returns on equity are higher.

Australia’s tax settings around negative gearing are also lower than other countries such as the UK, US and Japan. The Age Pension system also incentivises pensioners to hold wealth in housing, which reduces their measured wealth for means testing.

Tightening these tax and transfer settings could lower housing price growth by reducing how much wealth growth people expect from housing. These tax settings also favour the wealthy. Renters that cannot afford to buy their own home have no access to the tax-favoured investment vehicle that is housing.

Reforms in this direction would be politically difficult without a cultural shift in how Australians relate housing to wealth. But the trade-off may have to be faced. The desire to build wealth through housing price appreciation feels fundamentally at odds with the desire for future generations to be able to buy homes.

Nick Garvin is a Research Manager at e61 Institute specialising in microdata research for economic and financial-system policy.

For more information, please reach out to Nick via email at [email protected].