The Weekend Edition includes a market update plus Morningstar adds links to two additional articles.

Traditionally, bond markets are dull affairs, though not lately. In April, a fascinating thing happened: stocks markets tanked and bonds also fell. Traditionally bonds have offered a haven in plummeting equity markets - though not this time. Soon after, Moody’s downgraded the US’ sovereign credit rating.

This has caused some introspection among investors who are grappling with questions such as:

What’s behind these bond market ructions?

Why is government debt back on investor radars?

Why now?

Will bond market wobbles continue?

Is US debt really at risk?

Could bond market woes eventually impact stock markets?

The backstory

To get answers, it’s important to understand the context to recent events.

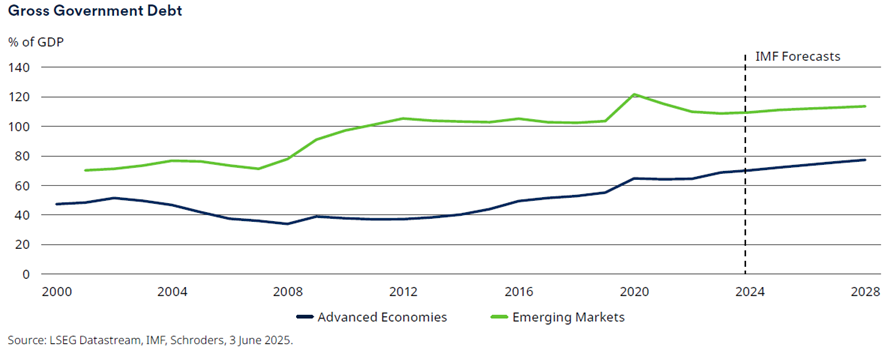

Government debt around the world has skyrocketed since the Global Financial Crisis. In 2008-2009, governments took on huge amounts of private debt to help save the financial system. A deflationary bust post that made it difficult for countries to grow their way out of this debt. And public debt levels had another leg-up during Covid as lockdowns and healthcare required huge additional spending.

With many major countries running large budget deficits, the IMF expects government debt to climb further in the years ahead, to about 100% of global GDP.

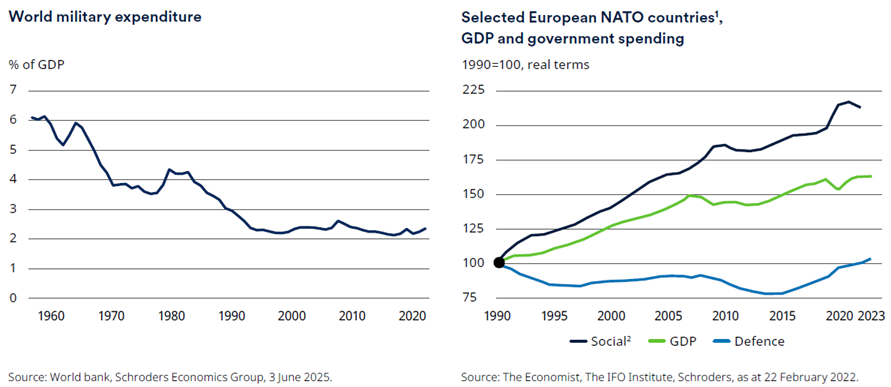

It’s not hard to see why the IMF believes budget deficits and government debts will continue to rise. Healthcare and social spending have ramped up significantly in recent years and as populations age across most major economies, it’s difficult to see this slowing down. It will not only pressure spending but also drain tax bases too.

Global defence spending is also expected to significantly increase to fund Ukraine’s resistance against Russia and plug the gap from America’s withdrawal from geopolitical hotspots. Lately, Europe has spent less than 2% of GDP on defence but the IMF and others think this could soon rise to 4-5%.

In an article last week, I outlined how Australian government spending jumped 9% last financial year, and that growth was unlikely to abate given the increasing health care and pension needs of our ageing population, the ever-expanding NDIS program, and forecast rises in defence expenditure from relatively low levels. That’s expected to result in growing budget deficits over the next decade.

Why are bond markets just waking up to sovereign debt risks?

Why are bond markets reacting now? After all, government debt in many major countries has been high for some time.

It can be put down to a combination of the following factors:

- The return to more normalized interest rates has pushed up interest costs on government debt and further increased budget deficits in the likes of the US.

- Trump’s tariff policies have fuelled concerns about the potential for inflation to reverse course and move higher again.

- Trump’s proposed tax and spending bill has added to market concerns about the large US budget deficit.

- US influence over the global economy means that rising Treasury yields are leading to higher yields elsewhere.

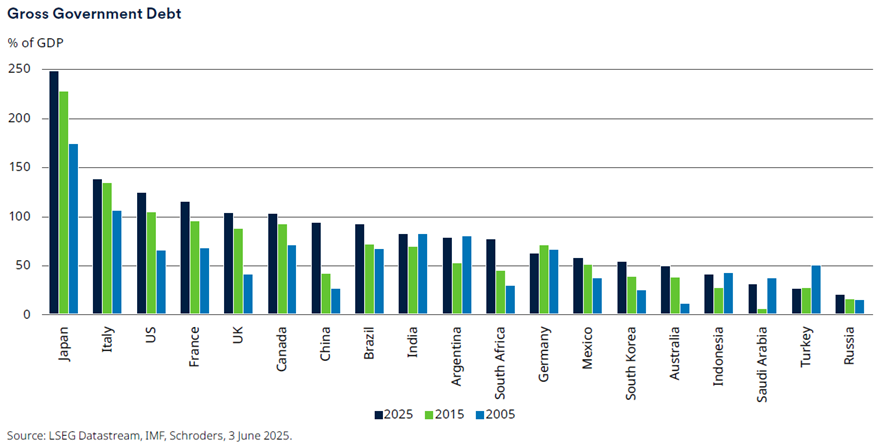

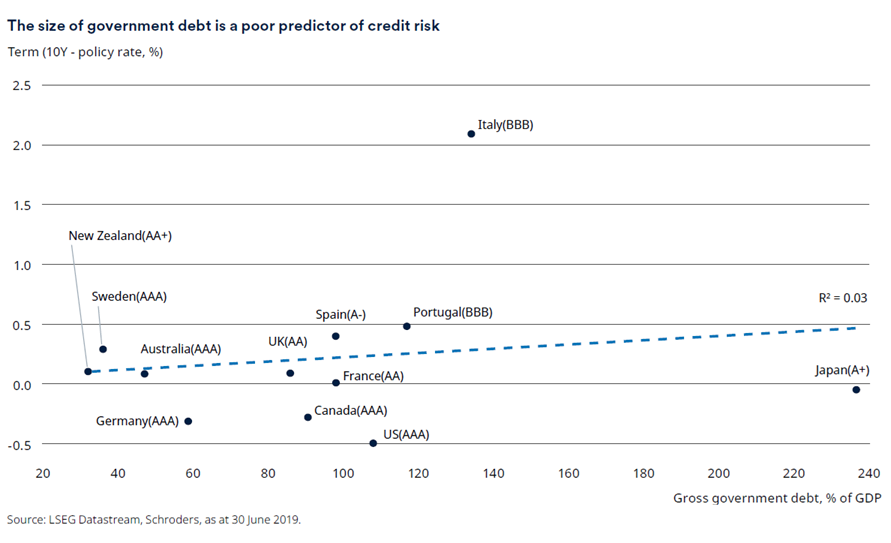

Markets haven’t been worried about government debt until now because this factor alone isn’t a precursor to a sovereign debt crisis. It was a good indicator for Sri Lanka’s crisis in 2022, when debt exceeded 100% of GDP. Yet, Argentina collapsed in 2001 with much small debt ratios of below 50% of GDP.

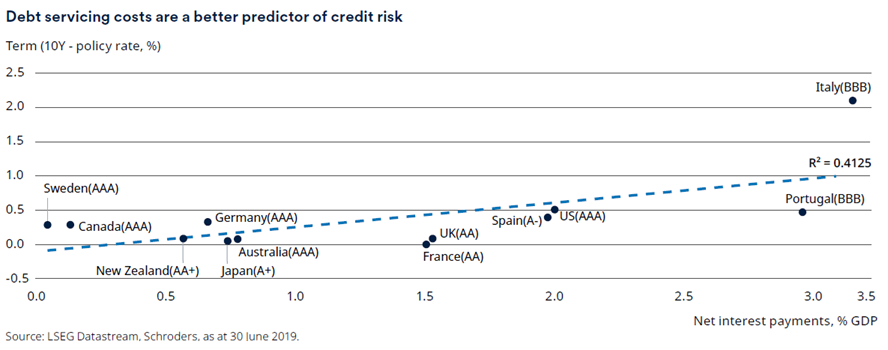

Schroders believes that other factors such as debt servicing costs and reliance on foreign funding are better predictors of credit risk. Because of that, it says markets are right to be concerned about higher interest rates and the strains that will put on government balance sheets.

The debt risk scorecard

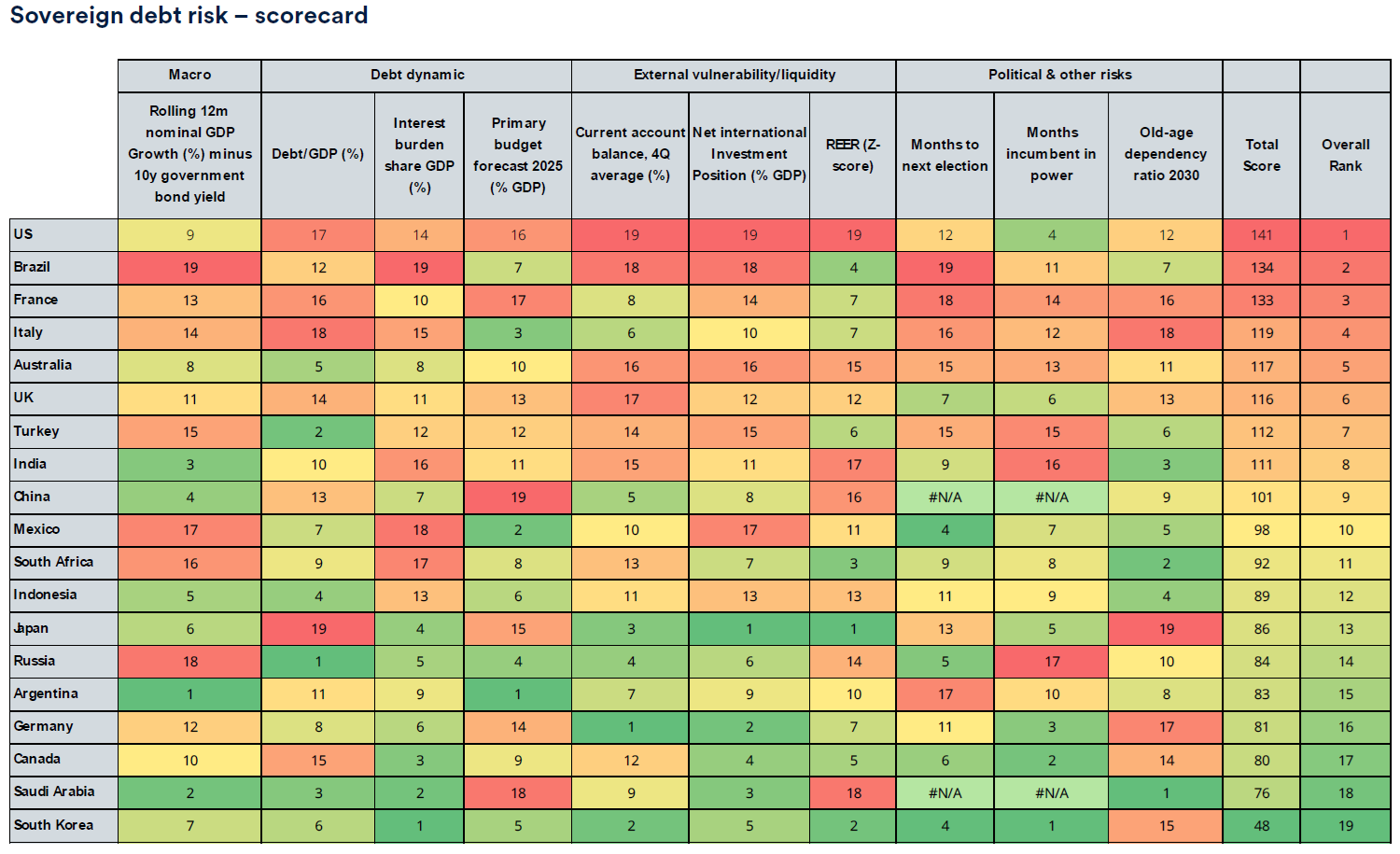

What’s the best way to assess government debt risk? Schroders has come up with a framework of four key components with 12 indicators.

The four components are:

- Macroeconomic - whether debt as a share of GDP is growing or shrinking.

- Debt dynamic – three indicators assessing current debt position, interest burden, and forecast spending for next financial year.

- External vulnerability/liquidity – three indicators to determine each economy’s vulnerability to the external environment.

- Political and demographic risks – capturing non-quantitative risks such as months to the next election to incorporate the potential for populist policy change as well as the old-age dependency ratio as an indicator of future budget pressure risk.

Here is Schroder’s final scorecard for the G20 countries. Each country is ranked from one to 19 (there are 19 countries in the G20 – go figure) in each category, and that adds up to a final score and overall rank.

Source: Schroders

The first thing to note is that of the top four countries with the worst score, four are developed markets – the US, France, Italy, and Australia. Of emerging markets, only Brazil makes the list. Developed markets may be the new emerging markets, it seems.

Why is the US deemed the biggest sovereign debt risk? Schroders says it’s primarily because of large, twin current account and budget deficits that mean the US is reliant on foreign capital inflows to sustain its debt pile. The firm notes America’s score would have been worse if not for solid nominal economic growth. And the relative strength in political and social factors for the US may be misleading given the newly elected Trump administration has created huge policy uncertainty, while its anti-immigration policies are likely to worsen the old-age dependency ratio over time.

There are caveats to this negative view, though:

“… the US has historically been a special case. It benefits from having the world’s reserve currency, a vast store of assets, and the most dynamic financial markets. There is speculation that the erratic nature of US policymaking has dampened the appetite of foreign investors to buy US assets. But so long as it lasts, this “exorbitant privilege” will continue to allow the US to sustain deficits and debt levels that would trigger crises in other countries.”

It shouldn’t come as a shock that France and Italy feature high up on the scorecard.

However, Australia ranking fifth is a surprise, at least to me. Looking at the chart, we’re in decent shape for the macro and debt dynamic categories. It’s the external vulnerability and political risk factors that let us down.

We rank the second worst when it comes to our current account balance and net international investment position. High foreign investment in primary sectors like mining is a key aspect here.

Australia is also let down by its short election cycles, which result in poor ratings for political risks.

Of other countries, Japan’s 13th ranking may seem counterintuitive given its notoriously huge gross government debt to GDP ratio of 251%. That debt isn’t seen as a large risk because of a high domestic savings rate and domestic ownership of the bond market. Also, Japan’s interest costs as a percentage of GDP are also low, making it less vulnerable to higher bond yields. Finally, Schroders thinks Japan’s external risks are low given its current account surplus and the country having the highest net international investment position in the G20.

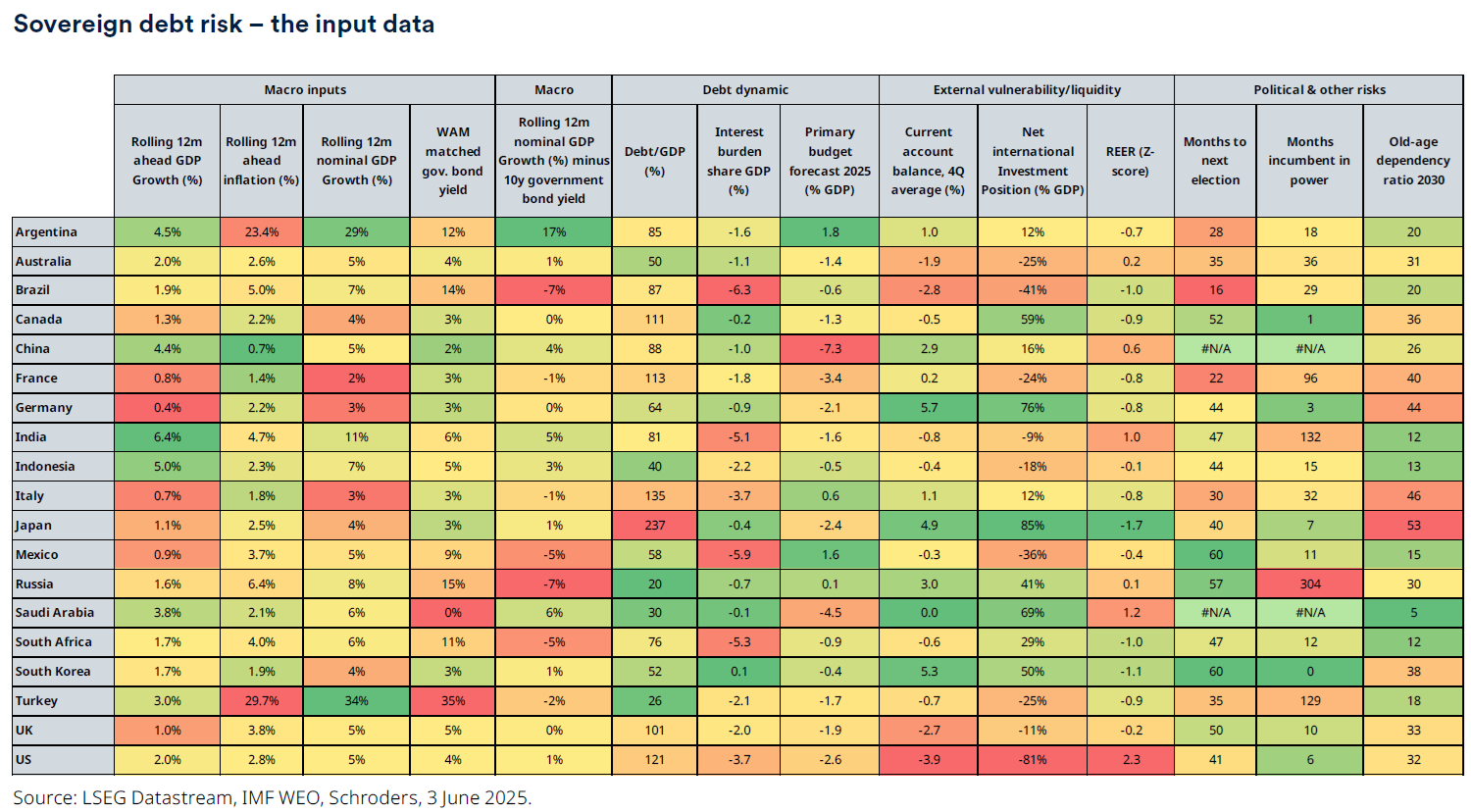

For those interested, here is the data that Schroders used for its sovereign debt risk rankings.

****

Debates about improving productivity are heating up as the Labor Government waits for the results of five separate inquiries on the issue. In my article this week, I suggest that franking credits should be part of the debate into reforming our languishing economy.

James Gruber

Also in this week's edition...

There has been a lot of comment and confusion in Firstlinks about how the new $3 million super tax will be calculated. The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) has put together a useful guide with seven examples of how the tax will affect different individuals.

Meanwhile, this week's whitepaper from Heffron has an explainer on the new tax for those with more than $3 million in super.

Will some of the world's biggest tech disruptors soon become the disrupted? Trent Masters says the rise of artificial intelligence could pose the greatest threat that Apple and Google have ever faced, and it opens a plausible path for their dominance to be challenged.

Defined benefit pensions were designed to offer security in retirement. But Peter Swan says that new tax policies and arbitrary limits now erode their value - especially for Australians who contributed their own savings to these plans.

Australia's farmland price boom has stalled. Nerida Conisbee investigates what's happened and why the sector may be entering a new and more nuanced phase.

Retail property has held up reasonably well given pressures on consumer spending. There's one niche, neighbourhood shopping centres, that has done especially well. Cromwell's Colin Mackay details why this niche offers sound prospects for both income and capital gain.

Two highlights from Morningstar this weekend. Mark Taylor shares his thoughts on the takeover bid for Santos, while Angus Hewitt weighs in on the pricing of Virgin Australia’s upcoming IPO.

It's no secret that IPOs in Australia have dried up, the upcoming Virgin float notwithstanding. ASIC has announced measures to encourage more listings, though Mark Humphery-Jenner believes they don't go far enough.

****

Weekend market update

In the US on Friday, stocks settled slightly lower on the S&P 500 after an initial upside burst ran out of steam, while Treasurys put in a mixed showing with two-year yields dipping four basis points to 3.89% and the long bond edging to 4.89% from 4.88% Wednesday. WTI crude settled at US$74 a barrel, gold traded sideways at US$3,369 per ounce, bitcoin ebbed below US$104,000 and the VIX dropped below 21.

Australia's share market on Friday gave up a five-week winning streak, as investors grappled with military conflict, global growth concerns and lofty valuations. The S&P/ASX200 fell 0.21% to 8,505.5, as the broader All Ordinaries lost 0.2% to 8,723.5. Over the week, the top-200 stocks fell roughly 0.5%.

The slump came after six sessions of surging oil prices amid escalating Israel-Iran conflict and as US President Donald Trump flagged potential American military involvement within two weeks.

The broader investor uncertainty then collided with heavy falls in big miners after weak economic data from China, as Rio Tinto plummeted to its lowest close since 2022.

Financials slipped 0.6% on Friday to finish roughly flat for a second week, a day after CBA etched its latest record high of $183.31 a share. All four big banks closed in the red, with ANZ facing the sharpest decline with a 2.5% slip to $28.39.

Australian energy stocks have had a massive week, surging almost 11% since Israel launched air strikes on Iran last Friday. Woodside is up 7.7% over the same period, while Santos has rallied 12%.

The IT sector had a surprisingly good week despite broader risk-off sentiment, edging 0.3% higher since Monday's open.

Looking ahead, while the Middle East conflict is likely to dominate headlines, it's also a massive week for macroeconomic data. Investors will be poring over local inflation figures, US economic growth, and manufacturing data for four of the world's seven largest economies.

From Shane Oliver, AMP:

Share markets were mixed over the last week as the escalating Israel/Iran war, with rising signs that the US may join in risking a disruption to oil supplies, kept investors cautious. For the week, US shares rose slightly after an initial reaction to the war on Friday the previous week, Eurozone shares fell, Chinese shares fell and the Japanese share market rose. Reflecting the uncertainty the Australian share market drifted down by around 0.5% with falls in material, utility and consumer staple shares more than offsetting gains in energy and IT shares. Bond yields were little changed – down slightly in the US and Germany but up in the rest of Europe, Japan and Australia. Oil prices drifted up another 4%, but gold, metal and iron ore prices fell. The $US rose slightly, and Bitcoin fell slightly but the $A was little changed.

While the impact on investment markets has so far been modest, the Israel/Iran conflict continues to pose a high risk:

- While the loss of life in any war is horrible, share markets only get really concerned if there is a meaningful disruption to economic activity – and the main way this can occur from conflicts in the Middle East is via disruption to global oil supplies as the region accounts for a third of oil production.

- So far the weeklong war has not threatened oil supplies and investors appear to be assuming that this will remain the case so US, global and Australian shares are only down around 1% from their level before Israel struck and while the oil price is up 11% it’s still below last year’s average levels and a bit of a non-event historically.

- However, with the US considering becoming involved in the conflict the risk of a meaningful disruption to oil supplies, even if only brief, is now high.

- Trump and most of his base do not want the US to enter another “forever war” bent on regime change in the Middle East. But Israeli success so far in destroying Iran’s military and nuclear capabilities appears to have changed the equation and is now temping Trump to join in and finish the job. Specifically, by using “bunker busting bombs” to destroy Iran’s underground Fordow nuclear facility and others.

- To this end Trump has demanded an “unconditional surrender” from Iran (presumably requiring complete dismantling of any nuclear program amongst other things).

- If Iran capitulates (to avoid a wipe out) then things will quickly settle down. But so far it has refused.

- Trump still sees a “substantial chance” that Iran will capitulate and negotiate but has indicated he will make a decision on whether to strike Iran “within the next two weeks”, which could be aimed at giving Iran time to think about it or for the US and Israel to get prepared or both.

- If the US does join in the war, the risks is that this could see Iran strike neighbouring oil producers (which it’s unlikely to want to do as it will end up in a wider war) or disrupt shipping through the Strait of Hormuz (which is more likely).

The bottom line is that US military intervention in Iran would mean an increasing risk of a significant disruption to global oil supplies – 20% of which flows through the Strait of Hormuz – which could push oil prices well beyond $US100 a barrel, possibly to around $US150/barrel. This would likely only be brief, as the US military would likely quickly move to stop Iran’s capabilities. But even if it’s for a few weeks or months it could still risk a significant blow to confidence regarding the economic outlook and so could push share markets down sharply.

The main way Australians would be impacted would be via higher petrol (and potentially gas) prices. So far the rise in oil prices this month of around $US15/barrel implies about a 15 cent a litre boost to petrol prices if sustained, which would add about 0.3% to headline inflation. This would not be enough to impact the RBA’s thinking on interest rates. Of course, the impact on petrol prices will be much bigger if oil supplies are disrupted – which could see petrol prices briefly spike to record highs.

Curated by James Gruber, Joseph Taylor, and Leisa Bell

Latest updates

PDF version of Firstlinks Newsletter

ASX Listed Bond and Hybrid rate sheet from NAB/nabtrade

Listed Investment Company (LIC) Indicative NTA Report from Bell Potter

Monthly Investment Products update from ASX

Plus updates and announcements on the Sponsor Noticeboard on our website