By my reckoning, the Australian economy has been through six cycles in the last 70 years, with low points in 1952, 1961, 1974, 1981, 1990 and 2009. Each slump had unique features, but all had two things in common: at the time, many people feared recession would last forever; and none did. I’ve also been through about six booms in the Australian economy. They also shared two things in common: many people thought boom times would last forever; and none did.

Cycles also occur in investment markets, largely caused by investors anticipating turning points in the economic cycle. At times, such expectations are well-based. Often, however, investor sentiment jumps at shadows or over-reacts:

- the share market is said to have predicted five of the last two recessions

- bonds sold off in 1994 when investors needlessly feared the return of rapid inflation and

- the Australian dollar made big moves from mid-2008 to 2011 that were not subsequently supported by the economic fundamentals.

Decisions would be far simpler if cycles were to disappear and instead, employment, business revenues, wages and investment returns moved gently on upward-sloping trend lines. It’s an extremely unlikely outcome and, were it to occur, long-term returns on shares and property, which are boosted by the premium for risk, would be lessened.

Why do we have to tolerate cycles?

Cycles occur because, being human, we are very much affected by the moods of others. When people around us are optimistic it’s easy to share their bullish expectations – spending more, borrowing more, and taking on riskier investments. When people around us are pessimistic, we tend to reduce spending, borrowing and investing.

Cycles can also reflect fiscal and monetary policies being adjusted too much and too late in the economic cycle with their impacts felt just when, or after, economic conditions change tack of their own accord. Credit flows can also generate or widen cycles through financing speculative excesses at the top of the cycle and crimping the funding of well-run businesses in recessions. In a small economy like Australia’s, cycles in the economy and investment markets are much affected by what’s happening, or expected to happen in US investment markets and the Chinese economy.

Have cycles been tamed?

There have been many attempts to tame the economic cycle and, periodically, we hear claims that the cycle is obsolete. In the late 1940s, economic planning was meant to moderate the cycle. Then came a couple of decades of confidence in ‘fine tuning’ economic activity through fiscal and monetary policies to eliminate cyclical swings. Later, monetary targeting took over. Following that, hopes were held that independent central banks, with charters requiring them to deliver low inflation, would smooth the traditional cycle.

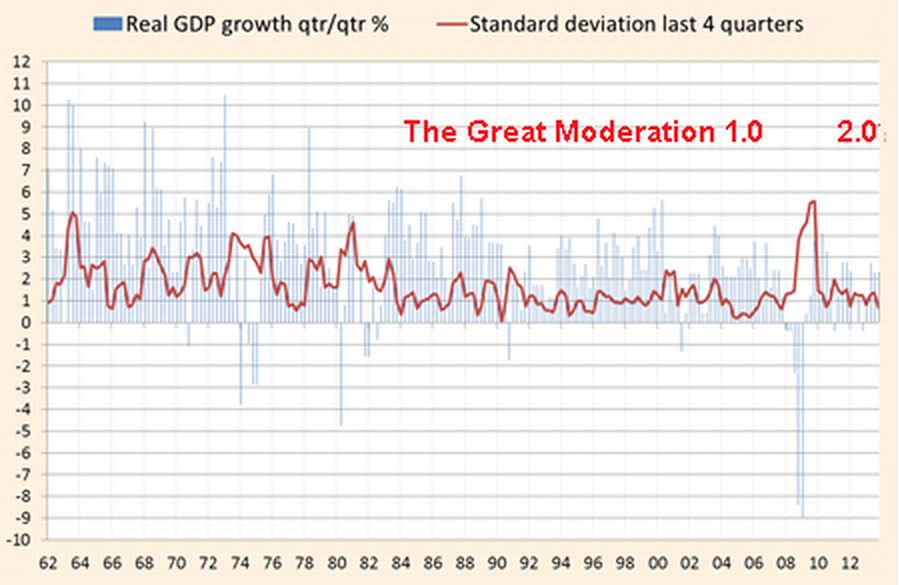

From the early 1980s to early 2008, year-by-year variations in US growth and inflation declined sharply and claims were made of the ‘Great Moderation’. In 2004, Ben Bernanke - then a senior central banker in the US and subsequently its head – gave the Great Moderation his strong endorsement. Alas, soon afterwards, the US economic cycle and cycles in investment markets were the widest and most damaging of those experienced in 70 years.

In recent weeks, some commentators on the US economy have spoken of ‘The Great Moderation, Version 2’. They say that, after the big swings in 2008 and 2009, the US economy will return to low-volatility growth and modest inflation which will be positive for risk assets in the medium term.

In my view, wide cycles will continue in the economy and investment markets. Certainly, past claims of pronounced declines in cyclicality turned out to be unjustified. And, as and when the money bases of the major economies start circulating, monetary and fiscal authorities are again likely to face big challenges in managing future cyclical swings in the economy and investment markets. Claims of the ‘new normal’ of secular deflation are also being withdrawn.

Real Growth in GDP in G7 Economies. Source: Fulcrum, Haver, FT

Some segments of investment markets and aspects of economic conditions are now moving back to where they were before the GFC hit hard in 2008. They are now ‘normal’ or ‘normalising’ again. As a result, the concept of the ‘new normal’, which came into vogue during the crisis, particularly in the US, is falling out of fashion.

A good example of the recent return to normal is the prospective price-earnings multiples of the US and Australian share markets. As a result, investors must allow that shares are no longer cheap. Meanwhile, the US unemployment rate is an example of something that’s normalising. However, cash rates here and abroad remain well below their normal levels.

That ‘New Normal’ is more likely a cyclical consequence

Of course, the long-term trends that we often use to define what is ‘normal’ are not set in concrete. They can change, but this doesn’t happen as often as is thought. ‘New paradigms’ are rare, but in investment markets and the economy we’ve seen the float of the Australian dollar, the introduction of franking credits on dividends, the sustained drop in Australian inflation from the early 1990s, and the economic reforms Deng Xiao-ping initiated in China.

From September 2009, senior managers in the world’s largest bond fund, PIMCO, gave shrill support to the concept of the new normal:

“… it’s time to recognize that things have changed and that they will continue to change for the next – yes the next 10 years and maybe even the next 20 years. We are heading into what we call the New Normal, which is a period of time in which economies grow very slowly as opposed to growing like weeds, the way children do; in which profits are relatively static; in which the government plays a significant role in terms of deficits and regulation and control of the economy; in which the consumer stops shopping until he drops and … starts saving to the grave.”

PIMCO, under new management, has dropped this expectation of a new normal dominated by secular stagflation. They say the US has “already left the most intense period of deleveraging that really created all sorts of pressures and adjustments that needed to happen in the economy”.

Certainly, a financial crisis as severe as the North Atlantic economies suffered from 2008 causes many people and businesses to change the ways they spend, borrow and invest. But these are generally better thought of as cyclical consequences that will normalise over time, rather than as a new normal that lasts for decades.

Don Stammer is an adviser to the Third Link Growth Fund, Altius Asset Management, Philo Capital and Centric Wealth. The views expressed are his alone. An earlier version of this article appeared in The Australian.